Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) is a chronic, bilateral, and recurrent allergic inflammatory disease primarily affecting the conjunctiva and cornea. It predominantly occurs in children and young adults, especially in males, and has a strong association with seasonal allergic responses. VKC is most prevalent in warm, dry climates and tends to exacerbate during spring and summer.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Geographic and Demographic Patterns

- Common in the Mediterranean region, Middle East, Africa, and South America.

- Affects predominantly males under the age of 20.

- Incidence often peaks between ages 5 and 15 and declines post-puberty.

Risk Factors

- Personal or family history of atopy (asthma, eczema, allergic rhinitis).

- Seasonal exposure to allergens such as pollen.

- Living in hot and dry climates.

Pathophysiology of VKC

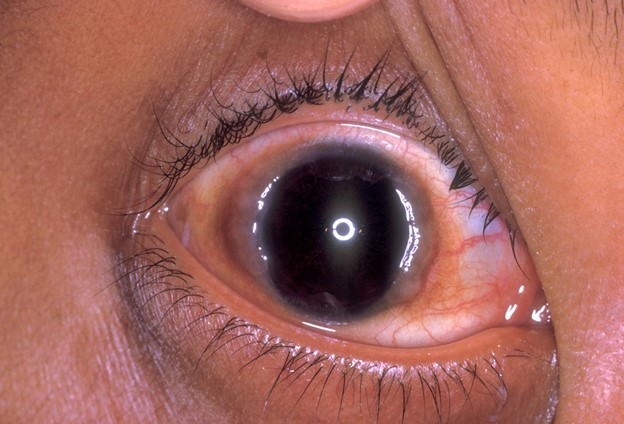

VKC is an IgE- and T cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction. The inflammation is triggered by environmental allergens, which activate mast cells and eosinophils, leading to the release of inflammatory mediators such as histamine, leukotrienes, and cytokines. These factors contribute to conjunctival hyperemia, papillary hypertrophy, and corneal involvement.

Clinical Classification of VKC

VKC presents in three main forms:

1. Palpebral Form

Characterized by giant cobblestone papillae (>1 mm) on the upper tarsal conjunctiva. Often accompanied by mucous discharge and ptosis due to eyelid swelling.

2. Limbal Form

Common in African populations, this form features gelatinous limbal thickening and Horner-Trantas dots—collections of eosinophils at the limbus.

3. Mixed Form

Displays both palpebral and limbal features and is considered the most severe manifestation.

Signs and Symptoms of VKC

Ocular Symptoms

- Intense bilateral itching

- Photophobia (light sensitivity)

- Foreign body sensation

- Mucoid or ropy discharge

- Blurred vision due to corneal involvement

- Watering and redness

Clinical Signs

- Conjunctival hyperemia

- Giant papillae on the tarsal conjunctiva

- Horner-Trantas dots

- Shield ulcers on the cornea (advanced cases)

- Corneal neovascularization and scarring (chronic cases)

Diagnostic Approach

Clinical Diagnosis

Diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on history and examination using slit-lamp biomicroscopy. Key features include:

- Seasonal recurrence

- Presence of giant papillae

- Horner-Trantas dots

- Absence of infectious symptoms like purulent discharge

Investigations (If Required)

- Conjunctival scraping: Eosinophil presence

- Serum IgE levels: Elevated in atopic individuals

- Skin prick test: Identifies specific allergen sensitivity

Differential Diagnosis

- Atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC): Affects older patients, often perennial.

- Giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC): Associated with contact lens wear.

- Seasonal allergic conjunctivitis (SAC): Milder and transient.

- Infectious conjunctivitis: Bacterial or viral origins with distinct clinical profiles.

Complications of Untreated VKC

- Corneal shield ulcers

- Pannus formation

- Keratoconus due to chronic eye rubbing

- Visual impairment from scarring or ulceration

VKC Management and Treatment Strategies

Non-Pharmacological Interventions

- Avoid allergens (e.g., dust, pollen, pet dander)

- Use of cold compresses

- Wearing sunglasses to reduce UV exposure and allergens

- Maintain strict hygiene and avoid eye rubbing

Pharmacological Therapy

1. First-Line Treatment

- Topical antihistamines (e.g., olopatadine, azelastine): Symptomatic relief

- Mast cell stabilizers (e.g., sodium cromoglycate, nedocromil): Prevent degranulation

2. Second-Line Treatment

- Topical corticosteroids (e.g., loteprednol, fluorometholone): For acute exacerbations

- Use short-term to avoid intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation, cataracts

3. Third-Line Therapy

- Topical immunomodulators (e.g., cyclosporine A 0.05%–2%, tacrolimus 0.03%–0.1%): Effective for steroid-sparing management of chronic VKC

4. Supportive Medications

- Lubricating eye drops to soothe the ocular surface

- Antibiotic prophylaxis if corneal ulcers are present

Surgical and Procedural Management

- Debridement of shield ulcers if non-healing

- Supratarsal steroid injection for refractory palpebral VKC

- Amniotic membrane transplantation in severe corneal involvement

Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

VKC generally subsides after puberty but may cause permanent visual impairment if inadequately managed. Early recognition and prompt treatment are essential for preserving visual function and quality of life.

Preventive Strategies and Patient Education

- Educate patients and caregivers about the importance of early symptom reporting

- Encourage allergen avoidance and environmental control

- Stress the importance of medication compliance

- Periodic ophthalmic check-ups to monitor corneal health and IOP

Frequently Asked Questions:

What causes vernal keratoconjunctivitis?

VKC is primarily caused by an allergic reaction to environmental allergens such as pollen, dust, and animal dander, particularly in genetically predisposed individuals.

Is VKC contagious?

No, VKC is not contagious. It is an allergic condition, not an infectious one.

Can VKC lead to blindness?

While VKC rarely leads to total blindness, severe or poorly managed cases can result in significant vision loss due to corneal damage.

How long does VKC last?

VKC is a chronic condition that can persist for several years, typically improving after puberty.

Can VKC recur after treatment?

Yes, symptoms often recur seasonally. Maintenance therapy and lifestyle modifications are necessary to control flare-ups.

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis is a severe ocular allergic disorder requiring early and sustained intervention. Through appropriate diagnosis, targeted therapy, and continuous monitoring, we can mitigate the risk of visual impairment and significantly improve patient outcomes. For clinicians, recognizing VKC’s hallmark signs is crucial, and for patients, adherence to management plans remains the cornerstone of successful long-term care.