Ventricular fibrillation (VF) is a life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia characterized by chaotic electrical activity in the ventricles, resulting in the cessation of effective cardiac output. As the most common cause of sudden cardiac death (SCD), VF requires immediate recognition and defibrillation to prevent irreversible brain damage or death. The disorganized impulses prevent the heart from pumping blood, making it a critical medical emergency.

Pathophysiology of Ventricular Fibrillation

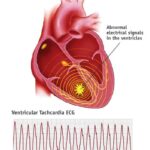

In ventricular fibrillation, electrical impulses originate from multiple ectopic foci within the ventricles, leading to erratic, uncoordinated contraction of myocardial fibers. As a result, the ventricles quiver instead of contracting, eliminating forward blood flow.

Underlying Mechanisms:

- Re-entrant circuits

- Triggered activity due to afterdepolarizations

- Abnormal automaticity in ischemic myocardium

Etiology: Common Causes of Ventricular Fibrillation

1. Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

- Myocardial infarction is the leading cause of VF.

- Scar tissue formation creates re-entrant arrhythmia circuits.

2. Structural Heart Disease

- Cardiomyopathies (dilated, hypertrophic, or arrhythmogenic)

- Congenital heart anomalies

3. Inherited Channelopathies

- Long QT Syndrome

- Brugada Syndrome

- Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT)

4. Electrolyte Disturbances

- Hypokalemia

- Hypomagnesemia

5. Drug-Induced

- Antiarrhythmics (Class I, III)

- Tricyclic antidepressants

- QT-prolonging agents

6. Other Triggers

- Electric shock

- Commotio cordis (blunt chest trauma)

- Illicit drug use (e.g., cocaine)

Clinical Presentation of Ventricular Fibrillation

Ventricular fibrillation results in an abrupt cessation of effective circulation. The typical clinical manifestations include:

- Sudden collapse or syncope

- Absence of pulse and respiration

- Unresponsiveness

- Cyanosis or pallor

- Seizure-like activity in some patients

Without immediate intervention, VF leads to anoxic brain injury within 4–6 minutes.

Diagnostic Evaluation

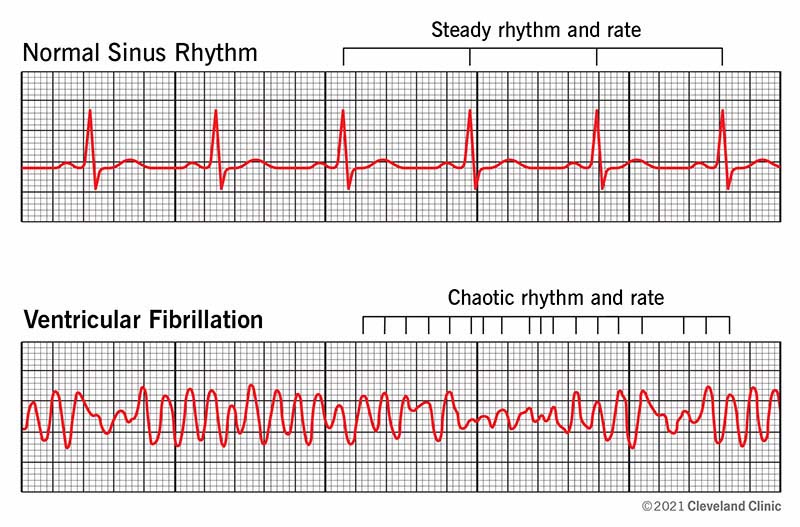

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

The gold standard for VF diagnosis.

- Findings: Irregular, rapid fibrillatory waves; no discernible QRS complexes, P waves, or T waves.

- Monomorphic vs. polymorphic patterns: Only relevant pre-VF, such as in ventricular tachycardia (VT).

Differentiation from Asystole and Pulseless VT

Accurate identification on ECG is critical for guiding therapy.

Emergency Management and Treatment

1. Immediate Defibrillation

- Primary intervention: High-energy unsynchronized shock.

- Best outcomes if performed within 3 minutes of arrest.

- Biphasic defibrillators preferred for higher efficacy.

2. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

- Initiate chest compressions immediately while preparing for defibrillation.

- Compression rate: 100–120/min; depth: 5–6 cm

3. Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS)

- Epinephrine: 1 mg IV every 3–5 minutes

- Amiodarone: 300 mg IV bolus if VF persists after defibrillation

- Magnesium sulfate: for torsades de pointes or low magnesium

4. Airway and Breathing

- Secure airway and ventilate with 100% oxygen

- Consider advanced airway management after initial defibrillation

Post-Resuscitation Care

Targeted Temperature Management (TTM)

- Maintain body temperature between 32–36°C

- Reduces neurological injury in comatose survivors

Coronary Angiography

- Indicated if VF resulted from suspected acute coronary syndrome

- May lead to revascularization

Hemodynamic and Neurological Monitoring

- Continuous ECG, pulse oximetry, and invasive blood pressure monitoring

- Assess brain function with EEG and neurological exams

Long-Term Management and Secondary Prevention

Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (ICD)

- Standard of care for survivors of VF without reversible causes

- Monitors rhythm continuously and delivers therapy for recurrent VF or VT

Antiarrhythmic Medications

- Amiodarone or sotalol may be used adjunctively with ICD

- Reduce shock burden in patients with frequent arrhythmias

Catheter Ablation

- Considered for refractory ventricular arrhythmias

- Especially effective in scar-related monomorphic VT leading to VF

Risk Factor Management

- Optimal treatment of coronary artery disease

- Control of heart failure and hypertension

- Avoidance of QT-prolonging drugs

- Correction of electrolyte imbalances

Prognosis and Outcomes

Survival rates after out-of-hospital VF remain low, though prompt defibrillation significantly improves outcomes. Neurological recovery depends on time to return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and the implementation of post-arrest care protocols.

Key predictors of poor prognosis:

- Delayed defibrillation

- Prolonged cardiac arrest

- No bystander CPR

- Severe metabolic acidosis

- Absence of brainstem reflexes post-resuscitation

Prevention of Ventricular Fibrillation

Primary Prevention

- ICD implantation in high-risk patients with reduced ejection fraction

- Management of modifiable risk factors (CAD, hypertension, lifestyle)

- Genetic screening and counseling in families with known channelopathies

Secondary Prevention

- Essential in survivors of cardiac arrest

- Long-term follow-up with cardiology and electrophysiology specialists

Ventricular fibrillation remains one of the most urgent and devastating cardiac emergencies. Immediate defibrillation, high-quality CPR, and rapid advanced cardiac care are critical to survival. Long-term prevention strategies, including ICDs, antiarrhythmic therapy, and risk modification, are vital to reducing recurrence and improving prognosis. Advancements in diagnostics and electrophysiological interventions continue to enhance outcomes for VF patients worldwide.