Neisseria meningitidis is a Gram-negative diplococcus recognized for its role in invasive meningococcal disease. However, it also colonizes the nasopharynx asymptomatically or causes upper respiratory infections (URIs), which serve as a precursor reservoir for more serious systemic illness. This article outlines the pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of URIs caused by N. meningitidis, with an emphasis on prevention and early clinical recognition.

Overview of Neisseria meningitidis in the Upper Respiratory Tract

N. meningitidis, commonly referred to as meningococcus, exists in multiple serogroups, including A, B, C, W, X, and Y. While it is a known cause of meningitis and septicemia, colonization of the nasopharynx without systemic invasion is common and often asymptomatic.

The bacterium can trigger localized upper respiratory symptoms in susceptible hosts or during outbreaks, particularly in enclosed populations such as military recruits, college dormitories, or refugee camps.

Pathogenesis of Meningococcal Upper Respiratory Infection

Following inhalation, Neisseria meningitidis adheres to the epithelial cells of the nasopharyngeal mucosa via pili and outer membrane proteins. It may cause localized inflammation or invade the bloodstream.

The capsular polysaccharide prevents phagocytosis, and IgA protease helps evade mucosal immunity, facilitating colonization and, in some cases, progression to systemic disease.

Transmission Dynamics and Carriage

Transmission of N. meningitidis occurs via respiratory droplets and close personal contact. Colonization rates in the general population vary from 5% to 35%, with peaks in adolescents and young adults.

Factors Enhancing Transmission and Infection:

- Crowded living conditions

- Active or passive smoking

- Recent upper respiratory viral infection

- Immunocompromised status

- Complement deficiencies

Clinical Manifestations of Meningococcal Upper Respiratory Infection

While many carriers remain asymptomatic, some develop non-invasive URIs due to mucosal irritation and inflammation.

Symptoms of Upper Respiratory Involvement

| Symptom | Description |

|---|---|

| Sore throat | Often the first symptom |

| Nasal congestion | Mild to moderate, sometimes with discharge |

| Headache | May accompany sinus pressure |

| Low-grade fever | Indicates localized inflammation |

| Malaise | General discomfort or fatigue |

| Hoarseness | In rare cases involving the larynx |

These symptoms typically mirror viral URIs, making differentiation based solely on clinical features difficult.

Diagnostic Workup for Neisseria meningitidis-Related URIs

Clinical Evaluation

- History of close contact or outbreak exposure

- Recent viral illness or immunosuppression

Laboratory and Imaging

- Nasopharyngeal swab with PCR: Highly sensitive for meningococcal DNA detection

- Culture of throat swab: Less sensitive but specific

- CRP and CBC: To rule out systemic involvement

- Blood culture: If systemic infection is suspected

- Lumbar puncture: Not indicated unless signs of meningitis are present

Antimicrobial Treatment of Localized Meningococcal Infections

While N. meningitidis URIs may be self-limiting in some cases, antibiotic therapy is often warranted due to the risk of progression.

Recommended Antibiotics

| Drug | Use Case |

|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone | Preferred for confirmed or suspected cases |

| Penicillin G | Effective in susceptible strains |

| Rifampin | Useful for eradication in carriers |

| Ciprofloxacin | Alternative for prophylaxis or eradication |

Empiric treatment should cover resistant strains, especially during outbreak conditions.

Infection Control and Public Health Considerations

Prophylaxis for Close Contacts

Due to the high risk of transmission, prophylactic antibiotics are recommended for:

- Household members

- Intimate partners

- Healthcare workers with direct exposure to secretions

Agents used for prophylaxis:

- Rifampin: 600 mg BID for 2 days (adults)

- Ciprofloxacin: Single 500 mg dose (adults)

- Ceftriaxone: 250 mg IM single dose

Isolation Protocols

- Droplet precautions for at least 24 hours after initiating antibiotics

- Avoid shared utensils, bedding, or oral contact

Vaccination Against Neisseria meningitidis

Vaccination is key in preventing both invasive and non-invasive forms of the disease.

Available Vaccines:

- MenACWY (quadrivalent conjugate): Covers serogroups A, C, W, Y

- MenB vaccine: For additional coverage, especially in outbreaks or immunocompromised individuals

Schedule:

- Adolescents: First dose at 11–12 years, booster at 16

- High-risk adults: As indicated by CDC guidelines

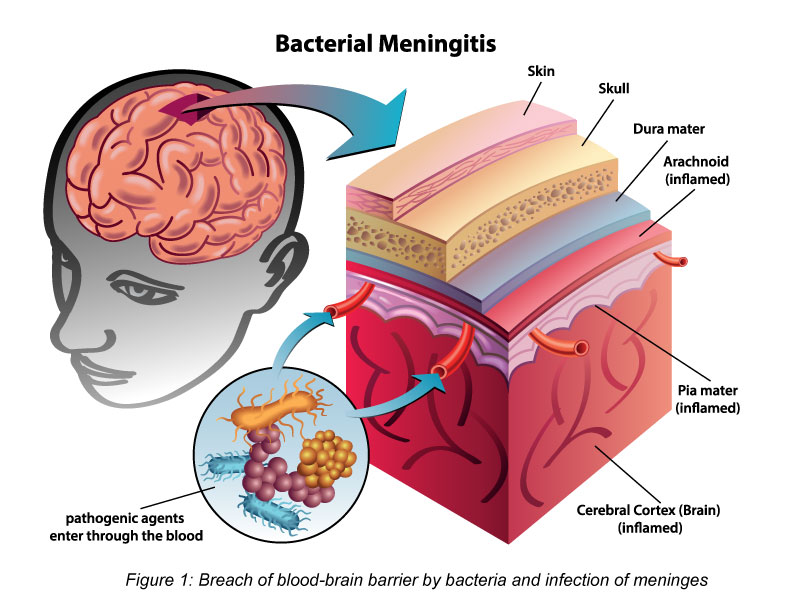

Complications from Untreated Meningococcal Upper Respiratory Infection

Although rare, untreated or unrecognized URIs can evolve into invasive disease, particularly in susceptible individuals.

Possible Complications:

- Bacterial meningitis

- Septicemia

- Purpura fulminans

- Pneumonia (rare but reported)

- Permanent neurological deficits in invasive disease cases

Epidemiology and Outbreak Trends

N. meningitidis outbreaks of respiratory infections often precede invasive disease clusters in high-density environments. Surveillance and rapid response, including mass prophylaxis and vaccination, are essential to contain such outbreaks.

Upper respiratory infections due to Neisseria meningitidis are an important yet underrecognized form of bacterial colonization and infection. While many cases remain mild or asymptomatic, the potential for progression to life-threatening illness necessitates clinical vigilance, appropriate antimicrobial therapy, and proactive public health measures.