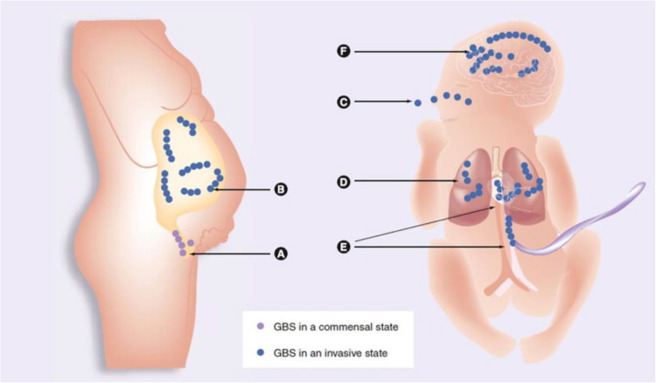

Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus or GBS) is a gram-positive, beta-hemolytic bacterium traditionally associated with neonatal infections. However, in recent decades, GBS has emerged as a significant pathogen in skin and skin structure infections (SSSIs), especially among immunocompromised adults, diabetics, and the elderly.

These infections range from mild cellulitis to severe, invasive soft tissue conditions, necessitating accurate diagnosis and effective management strategies to reduce morbidity.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors for GBS-Associated SSSIs

The incidence of S. agalactiae skin and soft tissue infections has increased, particularly in populations with underlying health issues.

Predisposing Risk Factors:

- Diabetes mellitus with peripheral vascular disease

- Obesity

- Immunosuppression (HIV, chemotherapy)

- Chronic skin breakdown (e.g., ulcers, dermatitis)

- Lymphedema

- History of recent surgery or trauma

- Older age (>60 years)

GBS colonization of the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts can serve as a reservoir for skin infection, especially in settings of skin barrier disruption.

Clinical Presentation of Streptococcus agalactiae Skin Infections

GBS infections are often misattributed to Staphylococcus aureus, yet clinical features may suggest streptococcal etiology.

Common Manifestations:

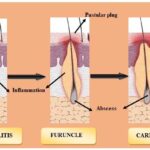

- Cellulitis: Erythematous, edematous, warm area with indistinct borders, often affecting the lower limbs

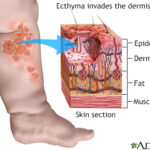

- Erysipelas: Superficial infection with sharply demarcated margins, commonly seen in the face and legs

- Wound Infections: Post-surgical or traumatic skin disruptions may become secondarily infected

- Abscess Formation: Though less common, may occur in conjunction with deeper soft tissue involvement

- Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections: Rare but life-threatening, requiring emergent surgical intervention

Systemic symptoms such as fever, chills, and leukocytosis are commonly associated with deeper infections or bacteremia.

Pathophysiology and Virulence Factors of GBS in Skin Infections

S. agalactiae exerts pathogenicity through multiple mechanisms:

- Capsular polysaccharide (CPS): Inhibits phagocytosis

- Beta-hemolysin/cytolysin: Lyses host cells and facilitates tissue invasion

- Surface proteins (e.g., C5a peptidase): Promote adhesion and immune evasion

- Biofilm formation: Enhances persistence in chronic wounds or on implanted devices

Diagnostic Approach to GBS Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Accurate diagnosis is essential for guiding antimicrobial therapy and identifying systemic involvement.

Recommended Diagnostic Workflow:

- Clinical Examination: Inspection for swelling, warmth, pain, systemic signs

- Microbiological Testing:

- Wound swab or aspirate culture

- Blood cultures in febrile or high-risk patients

- Laboratory Studies:

- CBC: leukocytosis may indicate systemic spread

- CRP/ESR: elevated in active infection

- Imaging:

- Ultrasound or MRI to detect abscesses or deep tissue involvement

Treatment Protocols for Skin and Skin Structure GBS Infections

The cornerstone of GBS infection treatment is antimicrobial therapy, guided by culture results and patient-specific factors.

Empiric and Targeted Antimicrobial Therapy:

| Infection Severity | Recommended Antibiotics |

|---|---|

| Mild to moderate | Penicillin, amoxicillin, or cefazolin |

| Penicillin-allergic (non-severe) | Cephalexin or clindamycin |

| Severe infections or bacteremia | IV penicillin G, ceftriaxone, or vancomycin (if beta-lactam allergy) |

| Polymicrobial infections | Add metronidazole or beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitors |

Duration of therapy typically spans 7–14 days, with longer courses indicated for deep or complicated infections.

Surgical Interventions:

- Incision and Drainage: Necessary for abscess management

- Debridement: Indicated in necrotizing or non-healing wounds

- Wound Care: Moisture-retentive dressings, antiseptic solutions, and compression therapy for lower limb infections

Complications of Untreated GBS Skin Infections

Failure to promptly diagnose and treat SSSIs caused by S. agalactiae may result in significant morbidity.

Notable Complications:

- Bacteremia and Sepsis

- Endocarditis in patients with underlying valvular disease

- Osteomyelitis with contiguous spread

- Deep tissue abscesses

- Chronic non-healing wounds

- Limb-threatening cellulitis, especially in diabetics

Prevention and Recurrence Mitigation

Preventive strategies are essential for high-risk individuals prone to recurrent GBS infections.

Key Measures:

- Optimal glycemic control in diabetic patients

- Regular skin care and inspection

- Compression therapy for lymphedema and venous stasis

- Prompt wound management for cuts, ulcers, and abrasions

- Consideration of prophylactic antibiotics in cases of repeated cellulitis

Emerging Trends in GBS Treatment and Research

As antimicrobial resistance trends shift, there is increasing focus on:

- Rapid point-of-care diagnostics for GBS identification

- Vaccine development targeting GBS serotypes

- Genomic surveillance to track virulence factors and resistance

- Biofilm-disrupting agents for chronic infection sites

- Combination therapies for polymicrobial and device-related infections

Skin and skin structure infections caused by Streptococcus agalactiae present a growing concern in adult and elderly populations, particularly those with comorbidities. Timely recognition, culture-guided antimicrobial therapy, and appropriate wound management are critical to ensuring favorable outcomes and preventing recurrence. A vigilant, evidence-based clinical approach remains essential in managing the evolving landscape of GBS-related SSSIs.