Severe Myoclonic Epilepsy in Infancy (SMEI), also known as Dravet Syndrome, is a rare but catastrophic epileptic encephalopathy beginning in the first year of life. This condition is characterized by prolonged febrile and afebrile seizures, developmental regression, and resistance to standard antiepileptic therapies. SMEI has a profound impact on neurological development, quality of life, and long-term outcomes.

Genetic Basis and Pathophysiology of SMEI

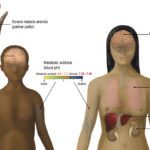

The majority of SMEI cases are caused by de novo mutations in the SCN1A gene, which encodes the alpha-1 subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.1. These mutations impair neuronal excitability, particularly in GABAergic inhibitory interneurons, leading to an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

- Prevalence: 1 in 15,000 to 1 in 40,000 live births globally

- Gender Distribution: Slight female predominance

- Onset: Typically between 5 and 8 months of age

- Risk Factors:

- Family history of epilepsy

- Early-life febrile seizures

- Genetic predisposition (SCN1A mutation carriers)

Clinical Features and Diagnostic Criteria

Early Seizure Onset

- Febrile seizures: Prolonged and often hemiclonic

- Afebrile seizures: Evolve within the first year

- Myoclonic jerks, focal seizures, and generalized tonic-clonic seizures follow

Developmental Regression

- Delayed milestones: Cognitive, motor, and language impairments emerge

- Behavioral disorders: Hyperactivity, autistic traits, and attention deficits

Photosensitivity and Temperature Sensitivity

- Seizures often triggered by:

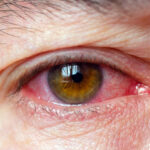

- Fever

- Warm baths

- Visual stimuli

- Emotional stress

Diagnostic Red Flags

- Seizures that increase in frequency and variety over time

- Refractoriness to standard antiepileptic medications

- Normal MRI in early stages despite ongoing neurological decline

Diagnostic Workup

Genetic Testing

- SCN1A gene sequencing: Identifies mutations in over 80% of SMEI patients

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

- Initially normal, later showing:

- Generalized spike-wave discharges

- Multifocal epileptiform abnormalities

- Photosensitive response

Neuroimaging

- MRI scans: Typically normal in early disease

- Later stages may show cerebral atrophy or hippocampal sclerosis

Differential Diagnosis

SMEI must be distinguished from other infantile-onset epileptic syndromes:

- Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+)

- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome

- Myoclonic-astatic epilepsy (Doose syndrome)

- Progressive myoclonic epilepsy

Treatment Strategies for SMEI

Antiepileptic Drug Therapy

Effective management requires a tailored approach using agents known to be beneficial in SMEI:

- First-line therapies:

- Valproic acid

- Clobazam

- Stiripentol (in combination with the above)

- Second-line options:

- Topiramate

- Cannabidiol (FDA-approved for Dravet Syndrome)

- Avoid sodium channel blockers such as carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and phenytoin, which can exacerbate seizures.

Dietary and Neuromodulation Approaches

- Ketogenic diet: High-fat, low-carbohydrate therapy shown to reduce seizure frequency

- Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS): May provide adjunctive benefit in refractory cases

Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

- Cognitive impairment: Most children experience intellectual disability

- Seizure persistence: Lifelong epilepsy, often requiring multi-drug therapy

- Mortality risk: Increased due to status epilepticus and SUDEP (sudden unexpected death in epilepsy)

Despite therapeutic advances, SMEI remains a chronic condition requiring intensive medical, educational, and psychological support.

Supportive and Multidisciplinary Care

Developmental and Educational Interventions

- Early intervention programs

- Special education services

- Speech and occupational therapy

Family and Psychosocial Support

- Genetic counseling for affected families

- Support groups and advocacy networks

- Mental health services for caregivers and patients

Research and Emerging Therapies

Gene Therapy

- Experimental efforts aim to restore Nav1.1 function using viral vectors

Precision Medicine

- Targeted treatments based on individual mutation profiles

Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs)

- Promising approach to correct abnormal splicing or expression of SCN1A

Global and Public Health Perspective

- Awareness: Delays in diagnosis remain common

- Access: Disparities in availability of genetic testing and therapy

- Policy: Need for rare disease support programs and pediatric neurology networks

Severe Myoclonic Epilepsy in Infancy represents one of the most challenging pediatric epileptic disorders. Early recognition, genetic confirmation, and a multidisciplinary treatment strategy are essential for mitigating neurological decline and improving quality of life. Ongoing research into disease-modifying therapies offers hope for future generations affected by this devastating condition.