Salicylate intoxication is a potentially life-threatening medical emergency resulting from the ingestion of toxic doses of salicylate-containing compounds, primarily aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid). This condition can arise from acute overdose or chronic therapeutic overuse, leading to systemic toxicity that affects multiple organ systems.

Timely identification and intervention are essential to mitigate serious complications such as metabolic acidosis, cerebral edema, renal failure, and even death.

Pathophysiology of Salicylate Toxicity

Salicylates exert their toxic effects through a combination of mechanisms that disrupt cellular respiration, acid-base balance, and neurological function.

- Mitochondrial uncoupling: Inhibits oxidative phosphorylation, increasing lactic acid and heat production.

- Stimulation of the respiratory center: Leads to primary respiratory alkalosis.

- Anion gap metabolic acidosis: Accumulation of salicylic acid and other organic acids.

- CNS toxicity: Due to salicylate crossing the blood-brain barrier.

The mixed acid-base disorder (respiratory alkalosis with metabolic acidosis) is a hallmark of salicylate poisoning.

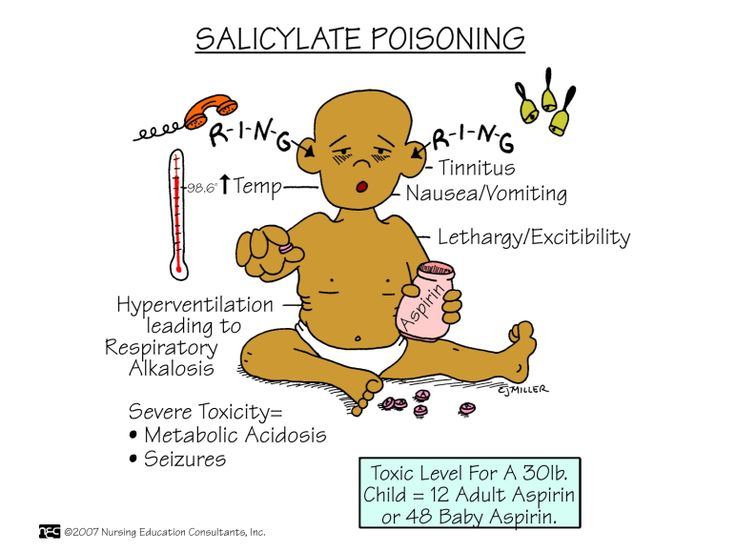

Clinical Presentation of Salicylate Intoxication

Early Symptoms (Mild to Moderate Toxicity)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Tinnitus (ringing in ears)

- Diaphoresis

- Hyperventilation

- Dizziness

- Tachypnea

Severe Toxicity

- Agitation, delirium

- Hyperthermia

- Pulmonary edema

- Seizures

- Coma

- Death (in cases of delayed or insufficient treatment)

Children and the elderly are particularly vulnerable to severe manifestations and atypical presentations.

Routes and Causes of Exposure

Salicylate intoxication may result from:

- Acute overdose: Ingesting large quantities intentionally or accidentally.

- Chronic toxicity: Repeated therapeutic use exceeding recommended doses, especially in the elderly or renal-compromised.

- Topical exposure: Methyl salicylate in creams or oils (e.g., wintergreen oil).

Common Sources

- Aspirin tablets

- Pepto-Bismol (bismuth subsalicylate)

- Topical liniments

- Herbal preparations containing salicylates

Diagnostic Evaluation and Laboratory Testing

Prompt recognition is critical, supported by a combination of clinical suspicion and laboratory data.

Initial Assessment

- Airway, Breathing, Circulation (ABCs)

- Neurologic and respiratory status

- History of ingestion (timing, dose, formulation)

Key Laboratory Investigations

- Serum salicylate concentration (interpret in clinical context)

- Arterial blood gas (ABG): mixed acid-base disturbances

- Electrolytes: anion gap, potassium

- Blood glucose

- Renal function tests

- Liver enzymes

- Coagulation profile

- Urinalysis for pH

Note: A normal salicylate level early in ingestion does not exclude toxicity; levels must be trended over time.

Severity Assessment and Risk Stratification

Done Nomogram (limited utility)

Used historically to predict toxicity based on time and serum level post-ingestion. However, not reliable for:

- Enteric-coated aspirin

- Chronic poisoning

- Multi-dose ingestion

Clinical Factors Indicating Severe Toxicity

- Serum salicylate > 100 mg/dL (acute)

- Altered mental status

- Severe acid-base derangements

- Rising salicylate levels despite therapy

Emergency Treatment of Salicylate Intoxication

Stabilization

- Ensure airway protection

- Supplemental oxygen

- IV access and fluid resuscitation

Decontamination

- Activated charcoal (1 g/kg): Effective within 1–2 hours of ingestion, repeat dosing for sustained-release products

- Avoid gastric lavage unless within 1 hour and life-threatening ingestion

Enhanced Elimination

- Urinary alkalinization:

- IV sodium bicarbonate (goal urine pH: 7.5–8.0)

- Monitor serum potassium; hypokalemia impairs urine alkalinization

- Hemodialysis: Indicated in:

- Severe acid-base imbalance

- Renal failure

- Altered mental status

- Very high salicylate levels (> 100 mg/dL acutely, > 60 mg/dL chronically)

- Refractory fluid overload or pulmonary edema

Supportive Measures

- Antipyretics avoided (aspirin-based)

- Glucose supplementation even with normoglycemia (neuroprotective)

- Frequent monitoring of labs and clinical status

Prognosis and Complications

With timely intervention, prognosis is favorable. Delays can lead to irreversible neurological damage, renal failure, and death. Chronic toxicity is often underdiagnosed and more dangerous due to subtle onset and delayed presentation.

Common Complications

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Renal insufficiency

- Cerebral edema

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Rhabdomyolysis

Prevention Strategies and Public Health Considerations

- Child-resistant packaging

- Clear labeling of salicylate-containing products

- Education about risks of overuse, particularly topical agents

- Caution in elderly and patients with renal impairment

- Avoidance in children with viral illnesses (risk of Reye’s syndrome)

Salicylate intoxication demands rapid recognition and aggressive intervention. Understanding the pathophysiological basis, recognizing early warning signs, and applying evidence-based management strategies are vital to optimizing outcomes. Health professionals must maintain high clinical suspicion, especially in vulnerable populations and atypical presentations.