Post-extubation laryngeal edema (PLE) is a potentially life-threatening complication occurring in a significant subset of patients following endotracheal intubation, particularly in intensive care settings. Manifesting as stridor and respiratory distress, untreated PLE can rapidly progress to complete airway obstruction, necessitating emergency re-intubation or tracheostomy. A well-structured prevention strategy is essential to ensure patient safety and successful weaning from mechanical ventilation.

Pathophysiology and Risk Factors of Laryngeal Edema After Extubation

Laryngeal edema results from mechanical trauma and mucosal ischemia induced by the endotracheal tube. Reperfusion injury upon tube removal exacerbates mucosal swelling, leading to airway narrowing. The subglottic region, especially in females and pediatric patients, is particularly vulnerable due to anatomical constraints.

Key risk factors include:

- Prolonged intubation (>48–72 hours)

- High endotracheal cuff pressures (>30 cm H₂O)

- Multiple intubation attempts or traumatic intubation

- Female gender (due to narrower airways)

- Pre-existing upper airway inflammation or infection

- Large tube relative to airway diameter

- Reintubation or failed extubation attempts

Early Identification and Assessment of Laryngeal Edema Risk

Cuff Leak Test (CLT)

The cuff leak test is the most widely used method to assess the likelihood of post-extubation laryngeal edema.

- Procedure: With the patient breathing spontaneously, the cuff is deflated and the difference between inspiratory and expiratory tidal volume is measured.

- Interpretation: A leak volume <110 mL or <10–15% of delivered tidal volume suggests a high risk for laryngeal edema and extubation failure.

Limitations: False positives may occur in cases of neuromuscular weakness or poor respiratory effort.

Pharmacologic Prophylaxis for Post-Extubation Laryngeal Edema

Corticosteroids

Prophylactic corticosteroids significantly reduce the incidence of laryngeal edema and re-intubation rates.

- Dexamethasone Regimen:

- Administer 5–10 mg IV every 6 hours for four doses, starting at least 12–24 hours prior to planned extubation.

- Mechanism: Reduces capillary permeability, leukocyte infiltration, and mucosal swelling.

- Methylprednisolone (alternative):

- 20–40 mg IV every 6 hours, used in similar dosing schedules.

Efficacy: Meta-analyses confirm corticosteroid prophylaxis is effective, especially in high-risk patients identified by a failed cuff leak test.

Non-Pharmacological Strategies for Edema Prevention

1. Optimal Tube Selection and Placement

- Use the smallest effective endotracheal tube size to reduce mucosal contact.

- Ensure correct tube positioning by verifying placement 2–3 cm above the carina.

- Avoid repeated intubation attempts by using skilled personnel and video laryngoscopy when needed.

2. Monitoring and Limiting Cuff Pressure

- Maintain cuff pressure between 20–30 cm H₂O.

- Use continuous cuff pressure monitoring systems to prevent mucosal ischemia.

- Periodic measurement with a cuff manometer every 8 hours in resource-limited settings.

3. Minimizing Duration of Intubation

- Daily assessment for readiness to extubate using spontaneous breathing trials (SBTs).

- Early tracheostomy consideration in patients expected to require prolonged mechanical ventilation.

Extubation Protocol for High-Risk Patients

1. Multidisciplinary Evaluation

Involve intensivists, respiratory therapists, and ENT specialists in patients with risk indicators for difficult airway.

2. Pre-Extubation Steroid Loading

Administer the first corticosteroid dose at least 12 hours prior, followed by subsequent doses every 6 hours.

3. Head Elevation and Humidified Oxygen

- Elevate the head of the bed to ≥30 degrees post-extubation.

- Administer humidified oxygen to reduce mucosal drying and irritation.

4. Post-Extubation Nebulized Epinephrine

For patients exhibiting mild stridor, nebulized racemic or L-epinephrine may provide temporary relief by vasoconstriction of edematous mucosa.

- Dose: Racemic epinephrine 0.5 mL of 2.25% solution diluted in 2.5 mL normal saline.

Emergency Airway Preparedness Post Extubation

In high-risk or borderline patients, airway equipment for reintubation should be immediately accessible.

Equipment Checklist:

- Video laryngoscope

- Endotracheal tubes of varying sizes

- Bougie and stylet

- Supraglottic airway devices (SGAs)

- Emergency tracheostomy and cricothyrotomy kits

Long-Term Considerations and Follow-Up

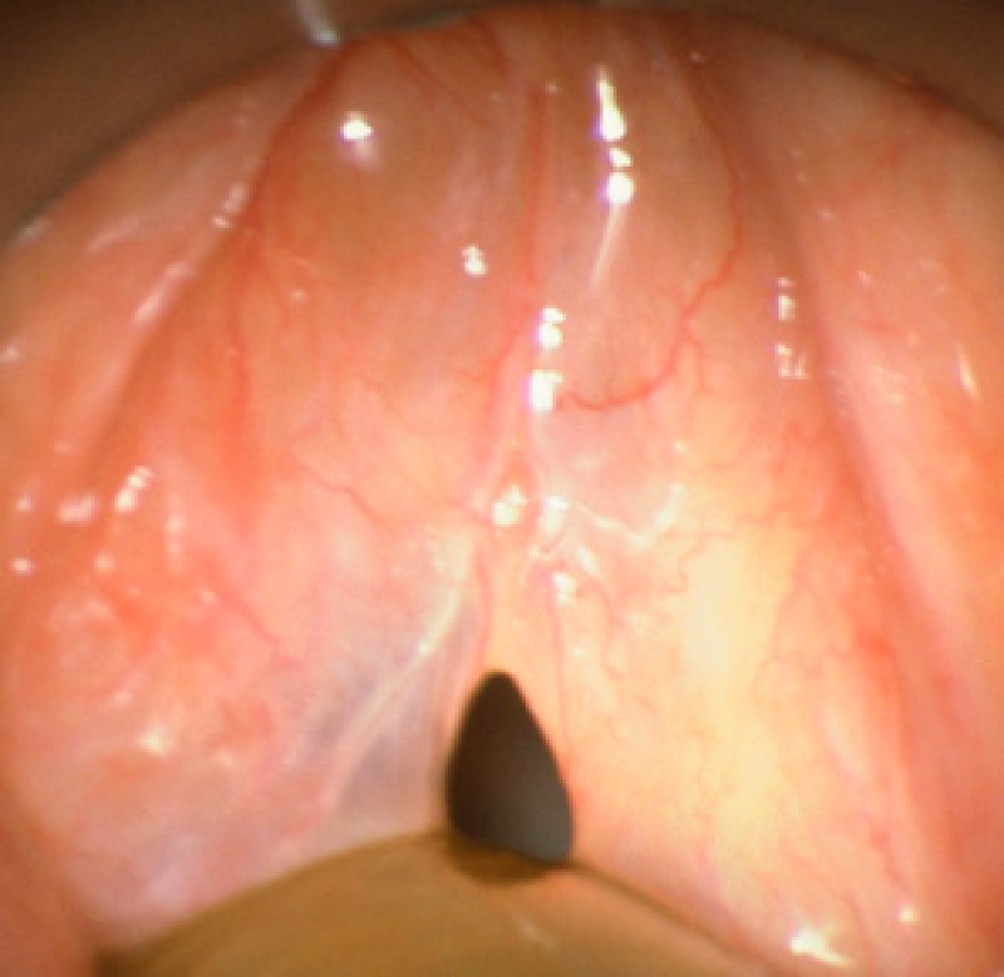

Fiberoptic Laryngoscopy

In patients with persistent voice changes or breathing difficulties post-extubation, fiberoptic laryngoscopy should be performed to evaluate for vocal cord dysfunction, scarring, or granulation tissue.

Documentation and Quality Improvement

All extubation failures due to laryngeal edema must be documented and reviewed in ICU quality assurance rounds to optimize future practices.

Preventing post-extubation laryngeal edema is crucial for safe airway management in critically ill patients. Through early risk identification, use of corticosteroid prophylaxis, cuff pressure optimization, and adherence to extubation protocols, we can substantially reduce extubation failure rates and associated morbidity. Vigilance, multidisciplinary coordination, and preparedness for airway emergencies remain the pillars of effective management.