Post-anesthesia respiratory depression is a potentially life-threatening complication that occurs following the administration of anesthesia, particularly during the immediate postoperative period. It is characterized by inadequate ventilation, reduced respiratory drive, and impaired gas exchange, which may result in hypoxia, hypercapnia, or even cardiopulmonary arrest if not promptly addressed.

Mechanisms and Causes of Post-Anesthesia Respiratory Depression

Central Respiratory Depression

The most prevalent mechanism involves central nervous system depression due to sedative or opioid administration. General anesthetics, benzodiazepines, and opioids suppress the medullary respiratory centers, reducing respiratory rate and tidal volume.

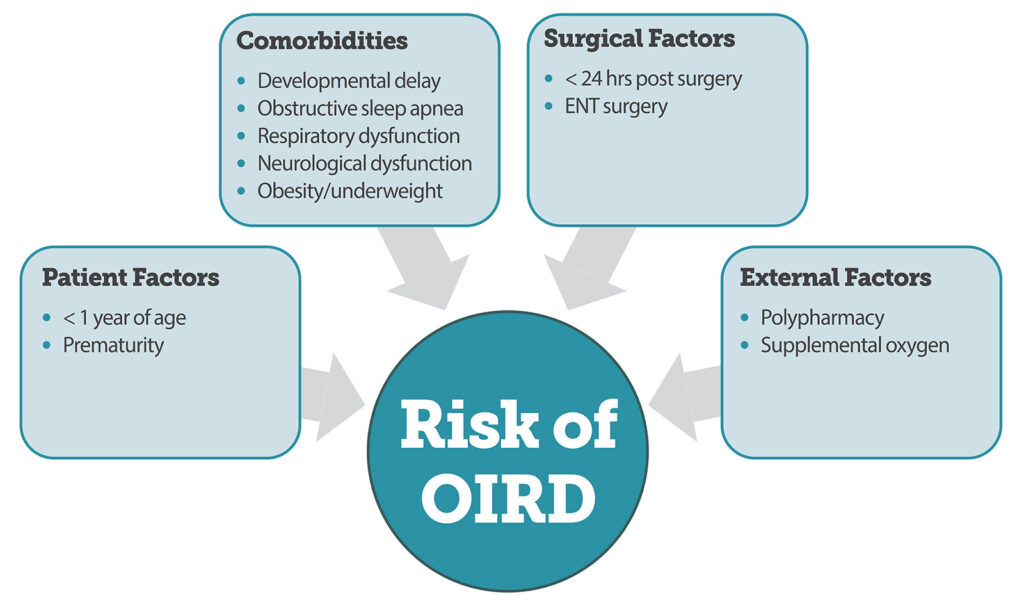

Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression (OIRD)

Opioids act on μ-opioid receptors within the brainstem, blunting the response to hypercapnia and hypoxia. The risk is compounded when opioids are combined with sedatives or in opioid-naïve patients.

Neuromuscular Blockade Residual Effects

Inadequate reversal or metabolism of neuromuscular blocking agents can lead to residual paralysis post-extubation, impairing diaphragmatic and intercostal muscle function.

Upper Airway Obstruction

Factors such as tongue prolapse, laryngospasm, or soft tissue obstruction—especially in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)—can cause post-extubation respiratory compromise.

High-Risk Populations and Predisposing Factors

Patient-Related Risk Factors

- Obesity (BMI > 30)

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

- Advanced age (> 65 years)

- Neuromuscular disorders

- Chronic opioid therapy

- Renal or hepatic impairment

Procedure-Related Risk Factors

- Major abdominal or thoracic surgeries

- Use of long-acting opioids intraoperatively

- Extended surgery duration

- Inadequate pain control leading to excessive opioid dosing

Medication-Related Risk Factors

- Combined use of sedatives, hypnotics, and opioids

- Use of long-acting or high-dose opioids such as morphine or methadone

- Residual effects of anesthetics or muscle relaxants

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

Early Warning Signs

- Shallow or slow breathing (bradypnea)

- Oxygen desaturation (SpO₂ < 90%)

- Altered mental status

- Cyanosis

- Hypoventilation or apnea episodes

- Respiratory acidosis on arterial blood gas (ABG)

Symptoms often manifest within the first few hours postoperatively, particularly during the transition from PACU (Post-Anesthesia Care Unit) to the general ward.

Diagnosis and Monitoring Strategies

Timely recognition relies on vigilant monitoring and the use of validated clinical tools.

Monitoring Techniques

- Pulse Oximetry: Continuous SpO₂ measurement; however, it may not detect hypoventilation in patients receiving supplemental oxygen.

- Capnography (EtCO₂ Monitoring): The gold standard for detecting hypoventilation early, especially during sedation.

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG): Confirms hypercapnia, acidosis, or hypoxemia.

- Sedation Scales: Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) or Ramsay Sedation Scale to assess depth of sedation.

Preventive Strategies and Best Practices

1. Risk Stratification and Preoperative Assessment

Evaluate for OSA, medication history, comorbidities, and previous anesthesia complications.

2. Multimodal Analgesia

Incorporate non-opioid analgesics such as NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and regional anesthesia to reduce opioid requirements.

3. Dosing Adjustments

Use the lowest effective opioid dose. Titrate slowly and monitor effects, especially in opioid-naïve or elderly patients.

4. Reversal Agents

Administer opioid antagonists (e.g., naloxone) or neuromuscular blocker reversal agents (e.g., neostigmine with glycopyrrolate or sugammadex for rocuronium) as needed.

5. Postoperative Monitoring

Continue respiratory monitoring for at least 24 hours post-op in high-risk patients. Employ continuous capnography in step-down or ICU settings.

6. Staff Education

Train PACU and ward staff to recognize early signs of respiratory depression and respond promptly with airway support and pharmacologic interventions.

Long-Term Implications and Follow-Up

Patients who experience post-anesthesia respiratory depression are at higher risk for complications such as:

- Unplanned ICU admissions

- Extended hospital stays

- Increased 30-day mortality

- Recurrent respiratory events

Follow-Up Recommendations

- Referral to sleep medicine if OSA is suspected

- Comprehensive medication review

- Adjustment of pain management plan for future procedures

- Patient education on opioid safety

Frequently Asked Questions:

How soon after anesthesia can respiratory depression occur?

It most commonly occurs within the first 24 hours, particularly in the initial 1–4 hours following PACU discharge when opioid levels peak.

Is post-anesthesia respiratory depression reversible?

Yes, with prompt recognition and appropriate intervention including airway support and pharmacologic reversal.

Can non-opioid medications cause respiratory depression?

Yes. Benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and certain anesthetics can also depress respiratory drive, especially in combination with opioids.

Is capnography better than pulse oximetry for monitoring?

Capnography provides earlier detection of hypoventilation, especially when supplemental oxygen masks signs of desaturation.

What is the role of naloxone in treatment?

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist used to reverse respiratory depression caused by opioid overdose. It must be dosed cautiously to prevent withdrawal and pain resurgence.

Post-anesthesia respiratory depression represents a critical perioperative risk that demands proactive assessment, vigilant monitoring, and timely intervention. By integrating patient-specific risk profiles, optimized analgesia protocols, and continuous respiratory surveillance, we can significantly reduce the incidence and severity of this complication. Ensuring safety in the postoperative phase is not merely about monitoring—it is about anticipating, educating, and intervening with precision.