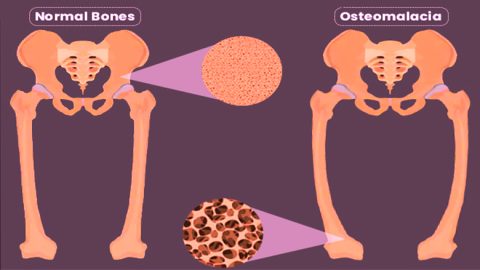

Osteomalacia is a metabolic bone disease characterized by the softening of bones due to impaired bone mineralization. It predominantly occurs in adults and is commonly caused by prolonged vitamin D deficiency. Unlike osteoporosis, which results in decreased bone mass, osteomalacia affects the quality of bone, making it weak, pliable, and susceptible to fractures and deformities. The condition shares similarities with rickets, which affects children during bone development.

Pathophysiology of Osteomalacia

Osteomalacia develops when there is inadequate mineralization of the osteoid, the bone matrix laid down by osteoblasts. This failure is primarily due to deficiencies in calcium, phosphate, or vitamin D—nutrients essential for proper bone mineralization.

Causes and Risk Factors of Osteomalacia

Nutritional Deficiency

- Vitamin D deficiency: Caused by inadequate sunlight exposure, poor dietary intake, or malabsorption disorders.

- Calcium and phosphate deficiency: Due to poor nutrition or gastrointestinal conditions.

Medical Conditions

- Chronic kidney disease: Alters vitamin D metabolism and phosphate balance.

- Celiac disease: Impairs nutrient absorption in the intestine.

- Liver disorders: Affect vitamin D activation.

- Tumor-induced osteomalacia: Rare paraneoplastic syndrome causing phosphate loss.

Medications

- Anticonvulsants (e.g., phenytoin, phenobarbital): Accelerate vitamin D metabolism.

- Antiretroviral drugs: Interfere with bone metabolism.

- Chelating agents: Bind calcium and impair its absorption.

Clinical Features and Symptoms

Osteomalacia often presents insidiously, with symptoms developing gradually over time:

- Diffuse bone pain: Especially in the lower back, hips, ribs, and legs.

- Proximal muscle weakness: Difficulty climbing stairs, rising from chairs, or walking.

- Skeletal deformities: Bowing of legs, waddling gait.

- Fractures: Pseudofractures (Looser’s zones) common in ribs and long bones.

- Fatigue and muscle cramps: Related to low calcium levels.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Laboratory Investigations

| Test | Typical Finding in Osteomalacia |

|---|---|

| Serum Calcium | Low or low-normal |

| Serum Phosphate | Low |

| Serum 25(OH) Vitamin D | Low |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | Elevated |

| Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) | Elevated (secondary hyperparathyroidism) |

These results reflect impaired bone metabolism and compensation mechanisms due to nutrient deficiencies.

Imaging Studies

- X-rays: May show pseudofractures, cortical thinning, and bone deformities.

- Bone Scans: Identify areas of abnormal bone remodeling.

- DEXA Scan: Indicates low bone mineral density but cannot distinguish osteomalacia from osteoporosis.

Bone Biopsy

In uncertain cases, a transiliac bone biopsy with tetracycline labeling can confirm osteomalacia by demonstrating increased unmineralized osteoid.

Differential Diagnosis

- Osteoporosis: Features low bone mass but normal mineralization.

- Paget’s disease: Localized bone remodeling disorder with elevated alkaline phosphatase.

- Hyperparathyroidism: Can also cause bone pain and demineralization.

Treatment and Management

The primary goal is to correct the underlying cause and restore proper mineralization.

Vitamin D Supplementation

- Cholecalciferol (D3) or Ergocalciferol (D2): Oral high-dose therapy, adjusted based on severity.

- Calcitriol: Used in renal patients who cannot convert vitamin D to its active form.

Calcium and Phosphate Replacement

- Calcium carbonate or citrate: Given orally to replenish stores.

- Phosphate salts: Prescribed in cases of phosphate deficiency, with careful monitoring.

Management of Underlying Disorders

- Celiac disease: Gluten-free diet.

- Chronic kidney disease: Dialysis, phosphate binders, vitamin D analogs.

- Tumor-induced osteomalacia: Surgical removal of the tumor.

Prevention Strategies

- Adequate Sunlight Exposure: At least 15 minutes daily on face, arms, or legs.

- Dietary Intake: Foods rich in vitamin D (fatty fish, fortified dairy), calcium (leafy greens, dairy), and phosphorus (meat, eggs).

- Regular Screening: In high-risk individuals (elderly, malnourished, housebound).

Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

With prompt diagnosis and proper supplementation, osteomalacia is reversible. Most patients experience significant improvement in symptoms within weeks to months. Chronic untreated cases, however, may result in persistent deformities and fractures. Adherence to therapy and follow-up evaluations are critical for long-term bone health.

Frequently Asked Questions:

What is the difference between rickets and osteomalacia?

Rickets affects children with developing bones, while osteomalacia occurs in adults with matured skeletons.

How is osteomalacia diagnosed?

Through clinical evaluation, laboratory tests showing vitamin D deficiency, and imaging showing bone changes.

Is osteomalacia the same as osteoporosis?

No, osteoporosis involves loss of bone mass; osteomalacia involves poor bone mineralization.

Can osteomalacia be cured?

Yes, if identified early and treated appropriately with nutrient supplementation and management of the underlying cause.

Who is at risk for osteomalacia?

Elderly individuals, those with poor nutrition, limited sun exposure, malabsorption syndromes, and chronic illnesses.

Osteomalacia is a preventable and treatable condition that requires a high index of suspicion for timely diagnosis. Awareness of its risk factors, clinical features, and appropriate therapeutic strategies ensures optimal outcomes. Restoring mineral balance and addressing underlying causes can dramatically improve bone strength, functionality, and quality of life in affected individuals.