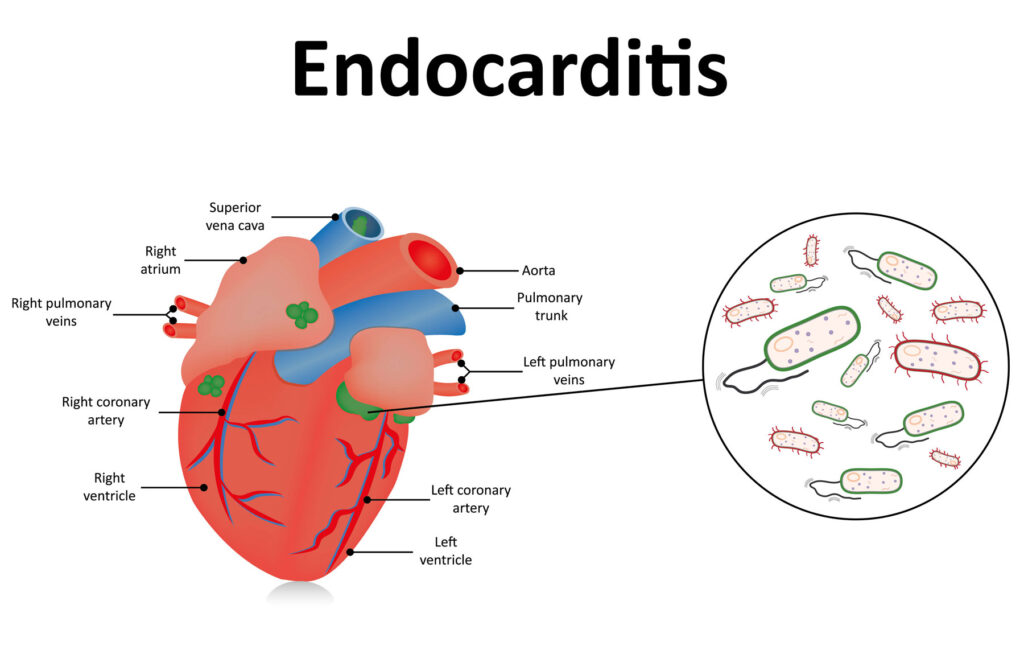

Enterococcal endocarditis (EE) is a significant clinical condition characterized by the infection of the endocardial surface of the heart, predominantly caused by Enterococcus faecalis. This pathogen is responsible for approximately 10% of all infective endocarditis (IE) cases, with a notable prevalence among the elderly population. The increasing incidence of EE, coupled with its association with healthcare settings and multidrug-resistant strains, underscores the necessity for a thorough understanding of its pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnostic methodologies, and therapeutic interventions.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Enterococcus faecalis and, to a lesser extent, Enterococcus faecium are the primary causative agents of EE. These facultative anaerobic Gram-positive cocci are commensals of the human gastrointestinal tract but can become opportunistic pathogens under certain conditions. The incidence of EE has risen in recent decades, particularly in developed countries, due to factors such as an aging population, increased use of invasive medical procedures, and the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics leading to selective pressure and the emergence of resistant strains.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of EE involves several key steps:

- Bacteremia: Entry of enterococci into the bloodstream, often originating from the genitourinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, or as a consequence of invasive medical procedures.

- Endothelial Adhesion: The bacteria adhere to the endocardial surface, facilitated by adhesins such as aggregation substance and enterococcal surface protein (Esp).

- Biofilm Formation: Following adhesion, enterococci form biofilms—a complex aggregation of microorganisms embedded in a self-produced extracellular matrix. Biofilms confer resistance to host immune responses and antimicrobial agents, complicating treatment efforts.

- Vegetation Development: The biofilm, along with host factors like platelets and fibrin, contributes to the formation of vegetations on heart valves, leading to impaired cardiac function and potential embolic events.

Clinical Manifestations

EE typically presents with a subacute course, with symptoms developing over weeks to months. Common clinical features include:

- Constitutional Symptoms: Fever, fatigue, malaise, night sweats, and weight loss.

- Cardiac Manifestations: New or changing heart murmurs, signs of heart failure, and conduction abnormalities.

- Embolic Phenomena: Embolization to various organs can lead to stroke, renal infarction, splenic infarction, or peripheral manifestations such as Janeway lesions and Osler nodes.

- Immunologic Responses: Glomerulonephritis, Roth spots, and rheumatoid factor positivity.

Diagnostic Approaches

Accurate and timely diagnosis of EE is crucial for effective management. The diagnostic process encompasses:

- Clinical Evaluation: A thorough history and physical examination to identify risk factors and clinical signs suggestive of endocarditis.

- Blood Cultures: Multiple sets of blood cultures are essential to isolate the causative organism. Enterococci are typically resilient and may require prolonged incubation periods.

- Echocardiography: Imaging modalities such as transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) are employed to visualize vegetations, assess valve function, and detect complications like abscess formation.

- Laboratory Tests: Inflammatory markers (e.g., elevated ESR, CRP), complete blood count showing anemia or leukocytosis, and urinalysis indicating microscopic hematuria may support the diagnosis.

- Modified Duke Criteria: This set of clinical, microbiological, and echocardiographic criteria aids in the diagnostic classification of IE into definite, possible, or rejected categories.

Treatment Strategies

The management of EE involves prolonged antimicrobial therapy, often necessitating combination regimens to achieve bactericidal effects. Treatment considerations include:

- Antibiotic Therapy:

- Ampicillin plus Gentamicin: Traditionally, this combination has been the cornerstone of treatment. However, concerns about nephrotoxicity and emerging resistance have prompted alternative approaches.

- Ampicillin plus Ceftriaxone: This regimen has demonstrated efficacy, particularly in strains with high-level aminoglycoside resistance, and is associated with a more favorable safety profile.

- Vancomycin: Reserved for patients with beta-lactam allergies or infections caused by resistant strains.

- Daptomycin: An option for multidrug-resistant enterococcal infections, often used in combination with other agents to enhance efficacy.

- Duration of Therapy: Typically, a 4- to 6-week course of intravenous antibiotics is required, depending on factors such as the presence of prosthetic material, complications, and the patient’s clinical response.

- Surgical Intervention: Indications for surgery include heart failure unresponsive to medical therapy, uncontrolled infection, large vegetations posing a high risk of embolization, and prosthetic valve involvement.

Prevention and Prognosis

Preventive measures focus on:

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis: Recommended for high-risk individuals undergoing procedures that may cause bacteremia.

- Infection Control Practices: Adherence to strict aseptic techniques during invasive procedures and judicious use of antibiotics to minimize the development of resistant strains.

The prognosis of EE depends on various factors, including the patient’s age, comorbidities, timely initiation of appropriate therapy, and the presence of complications. Despite advancements in medical and surgical management, EE remains associated with significant morbidity and mortality, necessitating ongoing research and optimization of treatment protocols.