Vitamin K is a fat-soluble nutrient critical for blood clotting, bone metabolism, and cardiovascular health. Due to its fat-soluble nature, absorption of vitamin K depends heavily on proper digestion and assimilation of dietary fats. Any disruption in fat absorption—whether from gastrointestinal disorders, liver dysfunction, or surgical interventions—can impair vitamin K uptake and lead to deficiency.

The Role of Vitamin K in Human Physiology

Vitamin K exists in two primary forms:

- Phylloquinone (Vitamin K1): Found in green leafy vegetables

- Menaquinones (Vitamin K2): Produced by gut microbiota and found in fermented foods

Both forms contribute to:

- Activation of clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X, and proteins C and S

- Regulation of osteocalcin for bone mineralization

- Inhibition of vascular calcification

Without adequate vitamin K, the body cannot properly form clots, increasing the risk of excessive bleeding.

Causes of Vitamin K Deficiency Due to Fat Malabsorption

1. Chronic Fat Malabsorption Syndromes

Conditions that impair digestion and absorption of fats inevitably reduce vitamin K assimilation. These include:

- Cystic fibrosis

- Celiac disease

- Crohn’s disease

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Short bowel syndrome

2. Hepatobiliary Disorders

Vitamin K absorption requires bile acids to emulsify fats. Disorders affecting bile production or flow reduce absorption:

- Primary biliary cholangitis

- Obstructive jaundice

- Liver cirrhosis

3. Long-Term Use of Certain Medications

- Antibiotics (disrupt gut flora responsible for K2 synthesis)

- Cholestyramine and orlistat (interfere with fat absorption)

- Anticoagulants like warfarin (antagonize vitamin K activity)

4. Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) Without Adequate Supplementation

Patients on TPN for extended periods without proper vitamin K inclusion are at risk of deficiency.

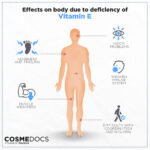

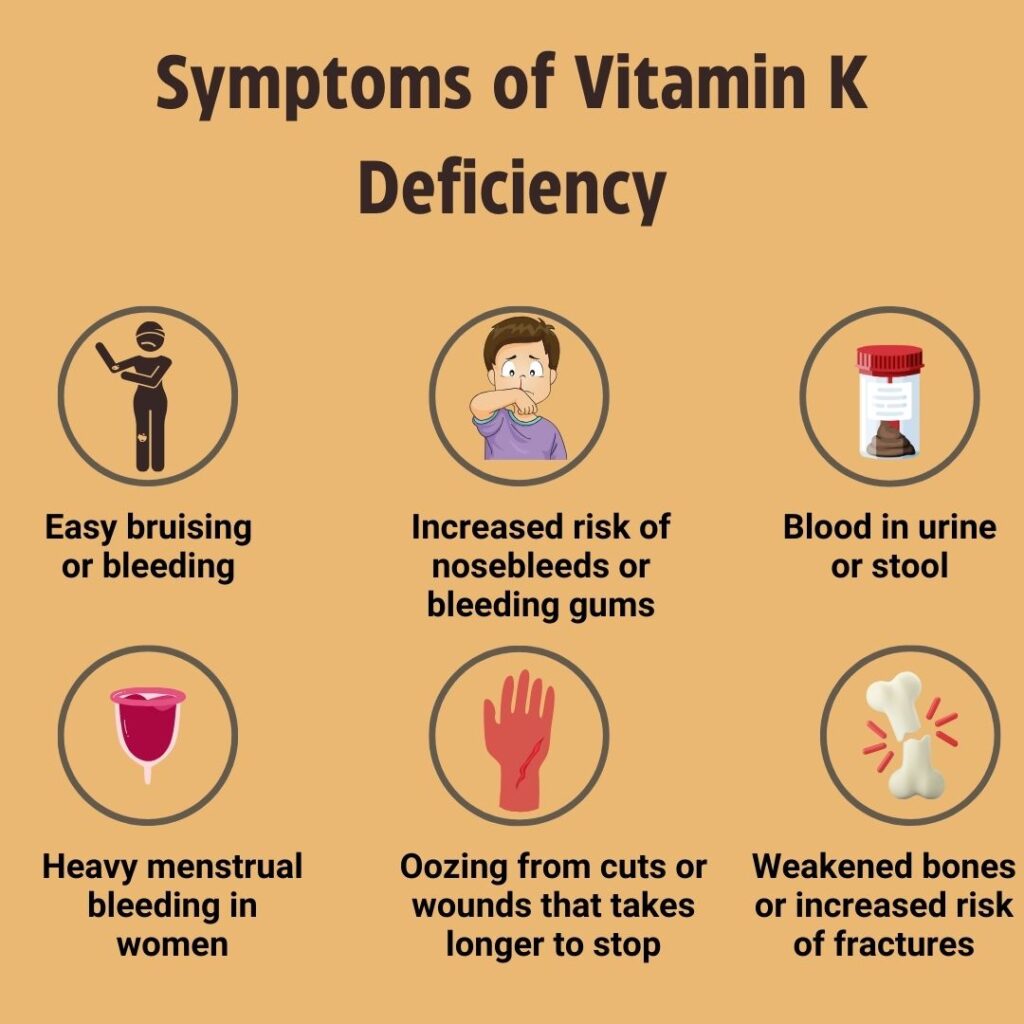

Clinical Manifestations of Vitamin K Deficiency

Deficiency results in impaired synthesis of coagulation factors, leading to:

- Easy bruising

- Prolonged bleeding from wounds or surgical sites

- Hematuria (blood in urine)

- Melena (black tarry stools)

- Menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding)

- Intracranial hemorrhage in severe neonatal deficiency

In newborns, the condition may present as Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding (VKDB), formerly known as hemorrhagic disease of the newborn.

Diagnostic Evaluation

1. Prothrombin Time (PT)

- The most sensitive indicator of vitamin K deficiency

- Prolonged PT with normal activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) indicates early deficiency

2. Serum Vitamin K Levels

- Direct measurement is possible but not routinely used due to high cost and variability

3. PIVKA-II Test (Proteins Induced by Vitamin K Absence)

- Detects abnormal, under-carboxylated prothrombin

- Useful in identifying subclinical deficiency

4. Stool Fat Analysis

- Confirms fat malabsorption as an underlying etiology

Dietary and Clinical Sources of Vitamin K

Incorporating vitamin K-rich foods is essential in both prevention and management.

| Food Source | Vitamin K Content (µg per 100g) |

|---|---|

| Kale | 817 µg |

| Spinach | 483 µg |

| Broccoli | 101 µg |

| Brussels sprouts | 140 µg |

| Natto (fermented soy) | 1103 µg (K2) |

| Egg yolk | 34 µg |

| Liver (beef/chicken) | 106 µg |

Treatment Strategies

1. Vitamin K Supplementation

- Oral supplementation is sufficient in mild cases: 1–10 mg/day

- Parenteral administration (IV or IM): Used in severe or acute deficiency, particularly in bleeding episodes

- In neonates, prophylactic injection of 0.5–1 mg vitamin K1 at birth is standard

2. Managing Underlying Malabsorption

- Treating the root cause—be it inflammatory bowel disease, liver dysfunction, or enzyme insufficiency—is essential for long-term correction

3. Fat-Soluble Vitamin Formulations

- For chronic conditions like cystic fibrosis, water-miscible forms of vitamin K improve absorption

- Multivitamin regimens with added vitamins A, D, E, and K are often prescribed

Preventive Measures for At-Risk Populations

- Regular monitoring of coagulation parameters in patients with fat malabsorption

- Neonatal prophylaxis for all infants, especially those born prematurely

- Vitamin K supplementation during long-term antibiotic use or TPN

- Dietary counseling to ensure sufficient intake of leafy greens and fermented foods

Long-Term Consequences of Untreated Deficiency

Persistent vitamin K deficiency due to malabsorption can result in:

- Chronic bleeding diathesis

- Anemia secondary to blood loss

- Increased risk of osteoporosis and arterial calcification

- Severe neonatal hemorrhage if not promptly addressed

In patients undergoing surgery, even subclinical deficiency can cause significant intraoperative bleeding complications.

Vitamin K deficiency due to fat malabsorption represents a clinically significant issue requiring timely recognition, diagnostic precision, and targeted treatment. By understanding the critical interplay between fat digestion and vitamin K absorption, we can more effectively manage and prevent this condition. Early intervention, dietary optimization, and monitoring of high-risk individuals form the cornerstone of successful long-term outcomes.