Tropical sprue is a chronic gastrointestinal disorder primarily affecting individuals residing in or traveling to tropical regions. It is characterized by malabsorption of nutrients due to abnormalities in the small intestine’s mucosal lining. The condition mimics celiac disease but is unrelated to gluten sensitivity and instead associated with an unidentified infectious etiology.

Epidemiology and Geographic Distribution

Tropical sprue predominantly occurs in South Asia, the Caribbean, and parts of Central and South America. Endemic regions include:

- Southern India

- Southeast Asia

- Puerto Rico

- Dominican Republic

- Haiti

It affects both natives and long-term visitors, with seasonal outbreaks suggesting an infectious origin. Although rare in developed nations, sporadic cases are occasionally seen in individuals returning from endemic areas.

Etiology and Risk Factors

The precise cause of tropical sprue remains elusive, but the prevailing hypothesis implicates a chronic bacterial infection—possibly involving Escherichia coli or Klebsiella species—that triggers an abnormal immune response and mucosal damage.

Contributing Factors:

- Prolonged exposure to unsanitary water or food

- Intestinal bacterial overgrowth

- Travel to or residence in endemic tropical areas

- Poor hygiene and nutrition

Pathophysiology: How Tropical Sprue Affects the Body

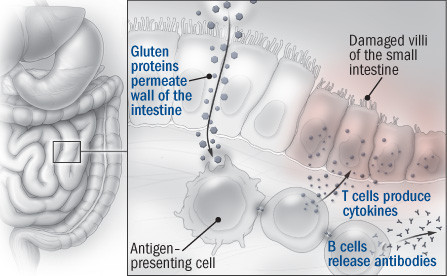

The pathological hallmark of tropical sprue is villous atrophy in the small intestine, leading to impaired nutrient absorption. This results in:

- Decreased absorption of fats, carbohydrates, and vitamins

- Deficiencies in folate and vitamin B12

- Electrolyte imbalance and weight loss

Clinical Presentation: Recognizing Tropical Sprue Symptoms

Tropical sprue typically presents with symptoms that evolve over weeks to months. The clinical picture includes both gastrointestinal and systemic signs.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms:

- Chronic diarrhea

- Steatorrhea (fatty, foul-smelling stools)

- Abdominal bloating

- Cramping and flatulence

Systemic Symptoms:

- Weight loss

- Fatigue

- Glossitis (inflamed tongue)

- Cheilitis (cracked lips)

- Anemia

- Peripheral neuropathy (due to B12 deficiency)

Diagnostic Evaluation

Clinical History:

- Recent travel or prolonged stay in tropical regions

- Persistent diarrhea unresponsive to conventional treatments

Laboratory Investigations:

- Complete blood count (macrocytic anemia)

- Low serum folate and vitamin B12

- Elevated fecal fat content

- D-xylose absorption test (reduced levels)

Endoscopy and Biopsy:

- Flattened villi observed in duodenal biopsy

- Inflammatory infiltrates in the lamina propria

- Exclusion of celiac disease (negative anti-tTG and anti-endomysial antibodies)

Differential Diagnosis

It is essential to differentiate tropical sprue from other malabsorption syndromes. Common differentials include:

- Celiac disease: Gluten-sensitive enteropathy, autoimmune mechanism

- Crohn’s disease: Inflammatory bowel disease with transmural involvement

- Giardiasis: Protozoal infection with similar diarrheal symptoms

- Whipple’s disease: Caused by Tropheryma whipplei, systemic involvement

- Lactose intolerance: Enzymatic deficiency, not villous atrophy

Tropical Sprue Treatment: A Multifaceted Approach

Effective treatment of tropical sprue involves a combination of antimicrobial therapy, nutritional supplementation, and dietary modifications.

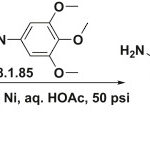

Antibiotic Therapy:

- Tetracycline (250 mg four times daily for 3–6 months)

- Alternatives: Doxycycline or ciprofloxacin in resistant cases

Nutritional Support:

- Folic acid (5 mg daily) — usually provides rapid symptomatic relief

- Vitamin B12 injections — essential for neurological recovery

- Iron, calcium, and other micronutrients as needed

Dietary Recommendations:

- High-protein, high-calorie diet

- Avoidance of lactose-containing products during acute episodes

Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

With appropriate and timely treatment, the prognosis for tropical sprue is favorable. Most patients respond within weeks to months, with normalization of bowel function and reversal of nutritional deficiencies.

Risk of Relapse:

- Persistent exposure to unsanitary conditions

- Incomplete or noncompliant treatment courses

Prevention and Public Health Considerations

For Residents and Travelers:

- Boil or filter drinking water

- Avoid raw or undercooked food

- Practice meticulous hand hygiene

- Take prophylactic folic acid when staying long-term in endemic areas

Public health efforts focused on improving sanitation and nutrition in endemic regions could substantially reduce disease incidence.

Tropical sprue remains a significant cause of chronic diarrhea and malabsorption in tropical regions. Early recognition and comprehensive treatment—including antimicrobial therapy and nutrient replacement—are essential for full recovery. Understanding its clinical spectrum, differential diagnosis, and treatment strategies enables effective management and prevention in both endemic and non-endemic settings.