Traveler’s diarrhea is the most common illness among international travelers, particularly those visiting regions with limited access to clean water and food sanitation. Among its many bacterial causes, noninvasive strains of Escherichia coli—primarily Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC)—are the leading pathogens. These organisms cause secretory diarrhea without penetrating the intestinal mucosa, making them clinically distinct from invasive pathogens such as Shigella or Salmonella.

Classification of Escherichia coli Causing Traveler’s Diarrhea

Noninvasive E. coli strains exert their pathogenic effects through toxin production or adherence mechanisms without breaching the intestinal epithelium.

Key Noninvasive Strains

- Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC)

Produces heat-labile (LT) and/or heat-stable (ST) enterotoxins that disrupt electrolyte and water transport, causing watery diarrhea. - Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC)

Induces characteristic attaching and effacing lesions that interfere with the absorptive function of intestinal villi.

Epidemiology of Noninvasive E. coli Infections in Travelers

Global Distribution

ETEC and EPEC are prevalent in:

- South and Southeast Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Central and South America

- Middle East

These regions often lack robust water treatment and food safety standards, facilitating fecal-oral transmission.

Risk Factors

- Consuming street food or unpeeled raw produce

- Drinking untreated water or beverages with ice

- Inadequate hand hygiene

- Reduced gastric acidity (e.g., PPI use)

- Young age and immunocompromised status

Clinical Manifestations of ETEC and EPEC Infections

Symptom Profile

- Watery diarrhea (often profuse but non-bloody)

- Abdominal cramps

- Bloating and nausea

- Low-grade fever

- Urgent need to defecate

Symptoms typically develop within 1–3 days of exposure and last 3–5 days without treatment. Vomiting and systemic illness are less frequent compared to viral gastroenteritis or invasive bacterial infections.

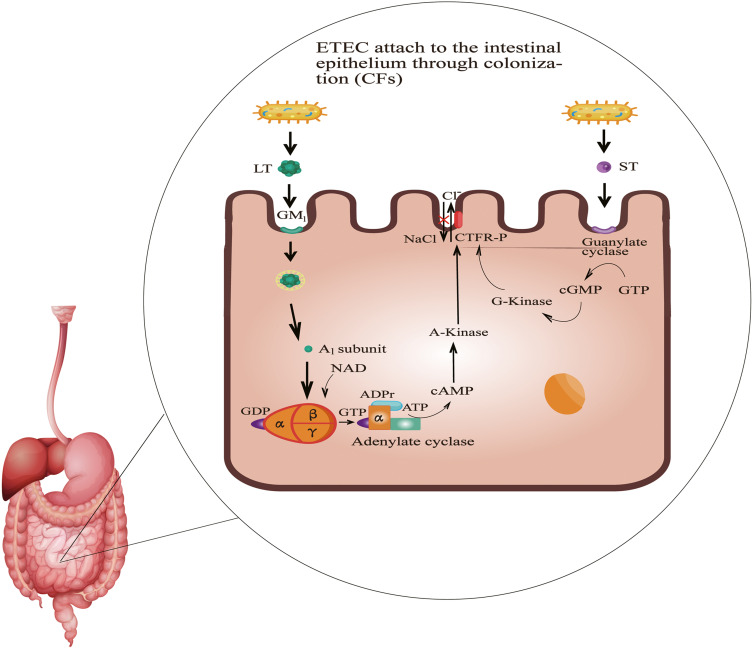

Pathogenesis of Noninvasive E. coli in Traveler’s Diarrhea

ETEC Mechanism

- LT toxin activates adenylate cyclase, raising intracellular cAMP.

- ST toxin stimulates guanylate cyclase, increasing cGMP.

- Both disrupt chloride ion channels, leading to water efflux into the intestinal lumen.

EPEC Mechanism

- Adheres to enterocytes using bundle-forming pili.

- Triggers signal transduction that effaces microvilli and alters electrolyte absorption.

- Causes a non-inflammatory diarrhea, especially in infants and occasionally adults.

Diagnostic Approach for ETEC and EPEC Infections

Most cases are diagnosed clinically based on travel history and symptomatology. However, laboratory confirmation may be necessary in prolonged or severe cases:

Diagnostic Tests

- Multiplex PCR panels: Detect enterotoxin genes and EPEC virulence factors.

- Stool culture with specific media: Less sensitive and time-consuming.

- Enzyme immunoassays (EIA): Detect LT and ST toxins in stool (limited availability).

Diagnosis is particularly warranted when symptoms persist beyond 7 days or when other etiologies are suspected.

Management of Traveler’s Diarrhea from Noninvasive E. coli

Rehydration Therapy

- Primary treatment is fluid and electrolyte replacement.

- Oral Rehydration Salts (ORS) should be administered regularly.

- Avoid sugary drinks and caffeine, which may worsen diarrhea.

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics are reserved for moderate to severe diarrhea or high-risk patients. Recommended regimens include:

| Antibiotic | Dosage | Duration | Region Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin | 500 mg once daily | 1–3 days | South Asia, Africa |

| Rifaximin | 200 mg TID | 3 days | Latin America, Asia (non-dysenteric) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 500 mg BID | 1–3 days | Use with caution due to resistance |

Note: Rifaximin is not effective for invasive pathogens and should not be used if there’s blood in stool or fever.

Adjunct Therapies

- Loperamide: Symptomatic relief; use only when fever and dysentery are absent.

- Probiotics: May reduce duration, though efficacy is strain-dependent.

Preventive Strategies for ETEC and EPEC Infection

Safe Food and Water Practices

- Consume only bottled or properly treated water.

- Avoid raw vegetables, unpeeled fruits, and unpasteurized dairy.

- Eat foods that are freshly cooked and steaming hot.

- Decline ice unless source is verified as safe.

Chemoprophylaxis

- Bismuth subsalicylate (e.g., Pepto-Bismol): 2 tablets 4 times daily; reduces risk by up to 60%.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis (e.g., rifaximin): Consider for high-risk travelers, though generally discouraged due to resistance risk.

Vaccines

- Dukoral: Offers partial protection against ETEC and cholera; approved in select countries.

- Efficacy is limited, and it is not routinely recommended for most travelers.

Special Considerations in Vulnerable Populations

Pediatric Travelers

- High risk of dehydration; avoid loperamide.

- Monitor closely for signs of fluid loss.

Elderly and Immunocompromised

- Greater risk of severe illness and complications.

- Consider early antibiotic initiation in moderate cases.

Pregnant Women

- Rehydration is primary; avoid unnecessary antibiotics unless clinically indicated.

Long-Term Consequences and Post-Infectious Syndromes

Though most infections resolve spontaneously, noninvasive E. coli may lead to:

- Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS)

- Persistent diarrhea (especially in EPEC)

- Malabsorption syndromes (rare)

Monitoring is recommended if symptoms extend beyond 10–14 days.

Traveler’s diarrhea caused by noninvasive strains of Escherichia coli, notably ETEC and EPEC, remains a dominant cause of morbidity in global travelers. With appropriate preventive measures, vigilant hygiene, and timely treatment, its burden can be significantly reduced. Risk-tailored counseling, early recognition of symptoms, and judicious use of antibiotics are critical components in managing this common travel-associated illness.