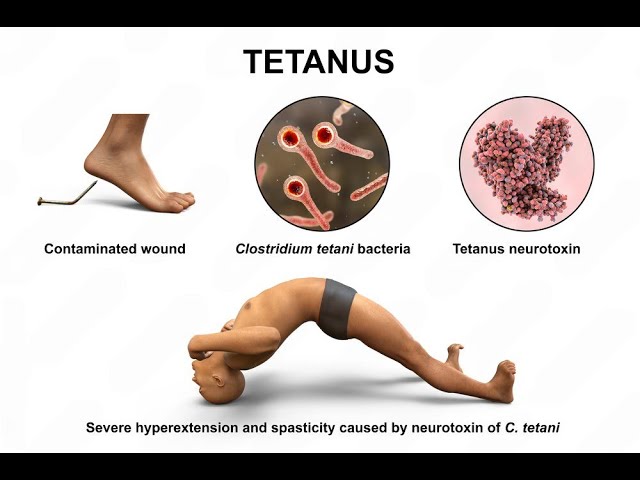

Tetanus is a severe, potentially life-threatening neurological disease caused by the neurotoxin tetanospasmin, produced by the bacterium Clostridium tetani. This anaerobic, spore-forming bacterium is widely distributed in soil, dust, and animal feces. Upon entering the human body through wounds or punctures, the spores germinate under low-oxygen conditions, producing the toxin that disrupts the nervous system.

Transmission and Risk Factors of Tetanus

Tetanus is not a contagious disease; it cannot spread from person to person. It is acquired when Clostridium tetani spores enter the body through:

- Puncture wounds from contaminated nails or sharp objects

- Animal bites or stings

- Burns or surgical wounds exposed to dirt

- Intravenous drug use with non-sterile needles

- Postpartum or post-abortion infections (neonatal tetanus in infants)

High-risk groups include individuals who are unvaccinated or incompletely immunized, those with poor wound care practices, and infants born in non-sterile conditions.

Pathophysiology of Tetanus

Once Clostridium tetani spores gain access to the body and anaerobic conditions are met, the bacteria release tetanospasmin. This neurotoxin binds irreversibly to peripheral nerve terminals and is transported to the central nervous system (CNS), where it blocks the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glycine.

This leads to uncontrolled muscular contractions and spasms, hallmark features of the disease.

Clinical Manifestations of Tetanus

The incubation period ranges from 3 to 21 days, typically averaging 8 days. The closer the site of infection is to the central nervous system, the shorter the incubation period and the more severe the symptoms.

Generalized Tetanus

The most common and severe form:

- Trismus (lockjaw): Inability to open the mouth

- Risus sardonicus: Fixed grimace-like smile

- Opisthotonos: Arching of the back due to muscle spasms

- Painful muscle stiffness in the neck, jaw, and abdomen

- Difficulty swallowing

- Severe autonomic dysfunction: fluctuating heart rate and blood pressure

- Respiratory compromise from laryngeal spasm or diaphragm involvement

Local Tetanus

Localized muscle spasms near the site of injury. May progress to generalized tetanus.

Cephalic Tetanus

Rare form following head injuries or otitis media; may present with cranial nerve palsies.

Neonatal Tetanus

Affects infants born to unimmunized mothers under unclean delivery conditions. Presents with:

- Inability to suck or feed

- Rigidity and spasms

- High mortality if untreated

Diagnosis of Tetanus

Tetanus is a clinical diagnosis, as no definitive laboratory test can confirm the condition. Key components include:

- Recent history of injury or wound

- Absence of tetanus immunization or unknown status

- Classic clinical features such as trismus, muscle spasms, and autonomic instability

Laboratory tests may help rule out other causes but are not specific for tetanus. Wound cultures may occasionally isolate Clostridium tetani, but negative results do not exclude the disease.

Treatment and Management of Tetanus

Emergency Care and Hospitalization

Tetanus is a medical emergency requiring intensive care. Treatment goals include:

- Neutralizing the unbound toxin

- Controlling muscle spasms

- Eliminating the source of infection

- Supporting vital functions

Key Treatment Components

| Treatment | Description |

|---|---|

| Tetanus Immune Globulin (TIG) | Administered intramuscularly to neutralize circulating toxin |

| Wound Debridement | Surgical cleaning to remove necrotic tissue and anaerobic environment |

| Antibiotics | Metronidazole is preferred; Penicillin G is an alternative |

| Muscle Relaxants | Diazepam or baclofen to control spasms |

| Sedation & Paralysis | For severe spasms requiring mechanical ventilation |

| Supportive Care | Ventilatory support, fluid balance, nutrition, and cardiac monitoring |

Tetanus Vaccination and Prevention

Vaccination is the cornerstone of tetanus prevention. The tetanus toxoid vaccine is administered in combination formulations such as:

- DTaP: Diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis (for children under 7)

- Tdap: Booster for older children and adults

- Td: Tetanus and diphtheria for adults

Immunization Schedule

| Age Group | Vaccine Type | Schedule |

|---|---|---|

| Infants and Children | DTaP | 5 doses at 2, 4, 6, 15-18 months, and 4-6 years |

| Adolescents | Tdap | 11–12 years |

| Adults | Td or Tdap | Every 10 years |

| Pregnant Women | Tdap | Between 27–36 weeks gestation |

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

Depending on the wound type and immunization history, individuals may require:

- Tetanus vaccine booster

- Tetanus immune globulin (TIG) for high-risk wounds in non-immunized individuals

Global Burden and Public Health Impact

Tetanus is rare in developed nations due to widespread vaccination but remains a public health challenge in low-resource countries. According to the World Health Organization (WHO):

- Neonatal tetanus causes thousands of deaths annually

- Elimination efforts focus on maternal immunization and clean delivery practices

The success of vaccination campaigns has significantly reduced global tetanus incidence, yet surveillance and continued immunization remain essential.

Frequently Asked Questions:

How is tetanus different from other bacterial infections?

Tetanus does not cause fever or inflammation like other bacterial infections but leads to neuromuscular dysfunction due to its neurotoxin.

Can a small cut cause tetanus?

Yes. Even minor injuries such as splinters, scratches, or insect bites can allow entry of C. tetani spores under favorable conditions.

Is tetanus fatal?

Without treatment, tetanus has a high mortality rate, especially in neonates. However, with prompt intervention, survival is likely.

How long does immunity last after the tetanus shot?

Immunity typically lasts 10 years, necessitating booster doses for continued protection.

Is there a cure for tetanus?

Tetanus can be managed and treated, but the damage caused by the toxin is not reversible. Recovery depends on new nerve growth.

Tetanus is a preventable but potentially fatal disease driven by bacterial neurotoxins. Its hallmark symptoms—muscle rigidity, spasms, and lockjaw—can be severe but are avoidable through timely immunization, proper wound care, and public health awareness. Global eradication efforts continue to target neonatal tetanus, while booster vaccination remains critical for long-term protection in all age groups.