Staphylococcal meningitis is a rare but life-threatening bacterial infection of the meninges, primarily caused by Staphylococcus aureus, including both methicillin-sensitive (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant (MRSA) strains. It represents a severe form of central nervous system (CNS) infection, often associated with neurosurgical procedures, head trauma, or hematogenous spread from distant infections. Prompt recognition, accurate diagnosis, and aggressive therapy are essential to prevent neurological deterioration and death.

Etiology and Pathogenesis of Staphylococcal Meningitis

Primary Causative Agents

- Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA): Most common in community-acquired cases.

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): Predominant in nosocomial infections or post-neurosurgical patients.

- Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS): Less virulent, but significant in device-related infections.

Routes of Infection

Staphylococcal organisms can invade the CNS through:

- Direct inoculation (neurosurgery, head trauma, lumbar puncture)

- Contiguous spread (from infected sinuses, ears, or skull osteomyelitis)

- Hematogenous dissemination (from bacteremia or endocarditis)

Clinical Manifestations of Staph Meningitis

Patients typically present acutely with signs of meningeal inflammation and systemic infection. Common symptoms include:

- High-grade fever

- Neck stiffness and resistance to flexion

- Severe headache

- Altered mental status or confusion

- Photophobia and phonophobia

- Seizures in severe cases

- Focal neurological deficits

- Positive Kernig and Brudzinski signs

In post-operative cases, symptoms may be more insidious and atypical, requiring a high index of suspicion.

Risk Factors and Populations at Risk

Staphylococcal meningitis is often linked to specific predisposing conditions:

- Neurosurgical interventions (especially craniotomies, VP shunts)

- Penetrating head injuries

- Skull base fractures

- Indwelling CNS devices

- Immunocompromised states (e.g., cancer, diabetes, HIV)

- Infective endocarditis

- Chronic hemodialysis or intravenous drug use

Nosocomial cases account for the majority of infections, especially with resistant organisms such as MRSA.

Diagnostic Approach and Laboratory Evaluation

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis

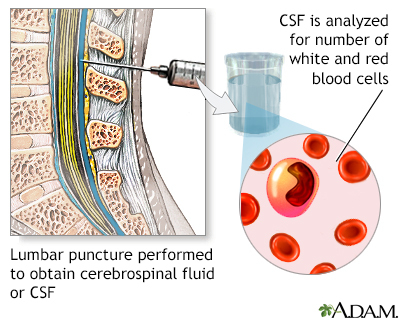

A lumbar puncture is crucial unless contraindicated by elevated intracranial pressure:

- Appearance: Turbid or purulent

- Cell count: Elevated WBCs (predominantly neutrophils)

- Protein: Markedly increased

- Glucose: Decreased

- Gram stain: Gram-positive cocci in clusters

- CSF culture: Definitive identification and sensitivity testing

Additional Diagnostics

- Blood cultures: Often positive, especially in hematogenous spread

- Neuroimaging (CT/MRI): To rule out mass lesions, abscesses, hydrocephalus

- PCR-based assays: For rapid bacterial DNA detection

Early diagnosis is critical; empirical therapy should begin before culture confirmation in high-risk cases.

Treatment Protocol for Staphylococcal Meningitis

Empirical Antibiotic Therapy

Immediate initiation of intravenous antibiotics is paramount:

- Vancomycin: Effective against MRSA and MSSA

- Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime: Broad-spectrum coverage

- Consider linezolid or daptomycin if vancomycin intolerance or failure

Therapy should be adjusted based on culture results and MIC values.

Duration of Treatment

- Typically 14–21 days for uncomplicated cases

- Prolonged therapy (up to 6 weeks) for associated complications (e.g., abscess, device involvement)

Adjunctive Measures

- Dexamethasone: May reduce inflammation and improve outcomes in select cases

- Surgical intervention: Drainage of abscesses or removal of infected CNS devices

- Supportive care: Management of seizures, intracranial pressure, and electrolyte imbalances

Complications and Prognosis

If not treated promptly, staphylococcal meningitis can result in:

- Septic shock

- Cerebral edema and herniation

- Subdural empyema

- Brain abscess

- Sensorineural hearing loss

- Cognitive impairment or paralysis

- Death

Mortality rates are significantly higher in MRSA infections and delayed treatment scenarios. Early antibiotic administration and neurosurgical consultation are crucial for survival and recovery.

Prevention and Infection Control

Hospital-Based Measures

- Aseptic technique during neurosurgical procedures

- Antibiotic prophylaxis before surgery

- Surveillance and decolonization for MRSA carriers

- Strict hand hygiene and environmental disinfection protocols

Device Management

- Use of antibiotic-impregnated shunts

- Timely removal or replacement of colonized CNS devices

Community Awareness

- Early recognition of skin or soft tissue infections

- Prompt treatment of bacteremia or endocarditis before CNS spread

Frequently Asked Questions

How does staphylococcal meningitis differ from other bacterial meningitis?

Unlike meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae or Neisseria meningitidis, staphylococcal meningitis is more commonly healthcare-associated and frequently linked to neurosurgical interventions or trauma. MRSA strains are notably aggressive and resistant to multiple antibiotics.

Can staphylococcal meningitis recur?

Yes. Recurrence is possible, especially in patients with persistent sources of infection (e.g., abscess, infected devices) or if antibiotics are prematurely stopped. Follow-up imaging and CSF analysis are recommended.

Is MRSA meningitis contagious?

No. While S. aureus can spread via contact, meningitis caused by MRSA is not typically transmitted from person to person. Standard infection control practices are effective in preventing transmission.

Staphylococcal meningitis represents a critical neurological emergency requiring swift and comprehensive management. With increasing rates of MRSA and complex neurosurgical procedures, clinicians must maintain vigilance for early signs, initiate empirical therapy promptly, and tailor treatment based on microbiological evidence. Optimizing prevention through stringent hospital infection control, patient education, and postoperative monitoring remains central to reducing incidence and improving outcomes.