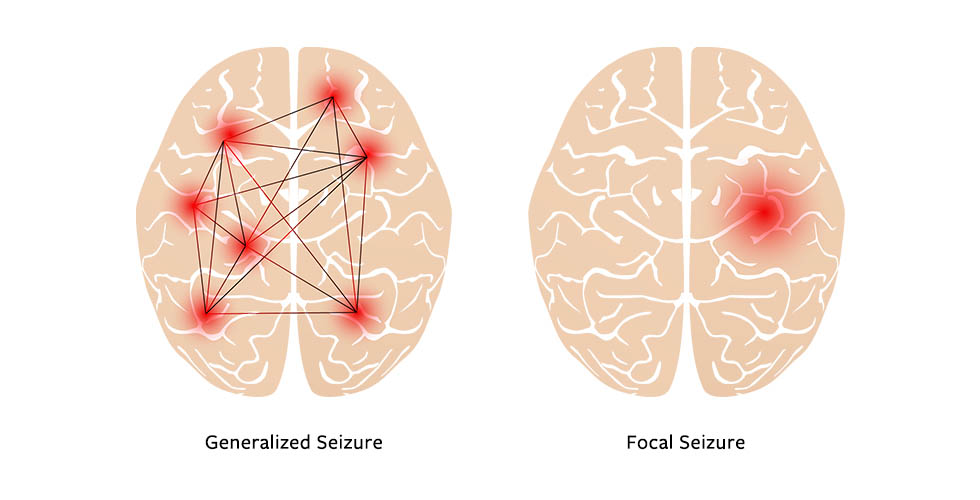

Simple-partial epilepsy, also known as focal aware seizures, is a form of epilepsy where seizures originate in a specific area of the brain and do not impair consciousness. Individuals remain fully alert during the episode, which typically lasts a few seconds to minutes. These seizures are among the most localized forms of epilepsy and can manifest with motor, sensory, autonomic, or psychic symptoms depending on the affected brain region.

Understanding the Pathophysiology of Simple-Partial Seizures

Focal aware seizures arise due to abnormal electrical discharges in one part of the cerebral cortex. These discharges may stem from structural abnormalities, prior trauma, infections, or idiopathic origins where no clear cause is identified. Depending on the lobe involved—frontal, temporal, parietal, or occipital—the symptomatology varies significantly.

Classification Based on Clinical Presentation

1. Motor Seizures

Involve movements such as facial twitching, jerking of limbs, or eye deviation. These seizures may “march” to adjacent body parts, known as Jacksonian march.

2. Sensory Seizures

Include tingling, burning, or numbness localized to one body area, or more complex sensations like distortion of body image or spatial perception.

3. Autonomic Seizures

Symptoms include flushing, palpitations, nausea, or sweating. These are often misinterpreted as panic attacks or gastrointestinal issues.

4. Psychic Seizures

Manifest with cognitive or emotional disturbances such as sudden fear, déjà vu, hallucinations, or out-of-body sensations.

Etiology: Common Causes of Simple-Partial Epilepsy

- Structural brain lesions: Tumors, strokes, arteriovenous malformations

- Head trauma: Especially penetrating injuries or post-concussive scarring

- CNS infections: Neurocysticercosis, encephalitis, meningitis

- Congenital malformations: Cortical dysplasia or genetic syndromes

- Metabolic imbalances: Hypoglycemia, hyponatremia

- Idiopathic: No identifiable structural or metabolic cause

Diagnostic Evaluation

1. Clinical History

Precise documentation of seizure onset, duration, type of sensation or movement, and awareness during the event is crucial.

2. Electroencephalography (EEG)

EEG remains a cornerstone in epilepsy diagnosis. In simple-partial epilepsy:

- Interictal EEG may show focal spikes or sharp waves.

- Video-EEG monitoring can correlate symptoms with electrical activity.

3. Neuroimaging

- MRI brain: Essential for identifying structural lesions.

- CT scan: Used when MRI is unavailable or in acute cases.

4. Laboratory Tests

Used to detect metabolic or infectious contributors (CBC, glucose, electrolytes, renal/hepatic panels).

Management Strategies for Simple-Partial Epilepsy

1. Antiepileptic Drug (AED) Therapy

Selection depends on seizure type, patient profile, and comorbidities.

Common First-Line AEDs:

- Carbamazepine: Especially effective in focal seizures

- Oxcarbazepine: Fewer side effects compared to carbamazepine

- Levetiracetam: Broad-spectrum, minimal drug interactions

- Lamotrigine: Preferred in women of childbearing age due to lower teratogenicity

2. Surgical Options

Reserved for medication-refractory cases with an identifiable epileptogenic zone.

- Temporal lobectomy

- Lesionectomy

- Focal cortical resection

3. Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

Considered in patients ineligible for surgery or with diffuse epileptogenic zones.

4. Lifestyle Adjustments

- Sleep regulation and stress management

- Avoidance of seizure triggers (e.g., flashing lights, alcohol)

- Regular medication adherence

Prognosis and Quality of Life

With appropriate treatment, many individuals achieve complete seizure control or significant reduction in frequency. However, the presence of underlying structural abnormalities may affect long-term outcomes.

Factors influencing prognosis:

- Early diagnosis and treatment initiation

- Etiology of epilepsy

- Response to AEDs

- Comorbid neurological or cognitive impairments

Pediatric Considerations

In children, simple-partial epilepsy may present with:

- Recurrent motor symptoms during wakefulness or sleep

- Age-specific syndromes such as benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS)

Management strategies remain similar but must be tailored to developmental status, growth, and long-term side effects of medication.

Differential Diagnosis

- Migraine auras: Visual or sensory phenomena without EEG correlation

- Panic attacks: Autonomic symptoms with anxiety and no focal EEG findings

- Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs): Especially when occurring in older adults

- Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES): Require video-EEG differentiation

Monitoring and Follow-Up

Routine follow-up ensures optimal seizure control and minimizes medication side effects. Recommended assessments include:

- Periodic EEGs

- Liver function and hematologic panels for AED toxicity

- Bone density monitoring in long-term AED users

- Psychosocial support and cognitive evaluations

Simple-partial epilepsy is a focal seizure disorder characterized by retained consciousness and localized manifestations. Early recognition, precise diagnosis through EEG and imaging, and individualized pharmacotherapy are pivotal in achieving seizure control. A multidisciplinary approach, involving neurologists, radiologists, and mental health professionals, is vital to managing both medical and psychosocial aspects of this condition.