Severe psychosis is a profound mental health condition characterized by a significant detachment from reality, often accompanied by hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized thought processes. It impairs daily functioning, distorts perception, and typically indicates an underlying psychiatric or neurological disorder. Individuals experiencing a severe psychotic episode require immediate clinical intervention to prevent harm and stabilize their mental state.

Core Symptoms of Severe Psychotic Episodes

Severe psychosis presents with a constellation of symptoms that can be divided into three primary domains:

Positive Symptoms

These represent distortions or excesses of normal functioning:

- Hallucinations: Auditory (most common), visual, olfactory, or tactile

- Delusions: Fixed, false beliefs resistant to reasoning, such as paranoia or grandiosity

- Disorganized Thinking: Incoherent speech, derailment, or tangentiality

- Agitation and Catatonia: Either hyperactivity or a lack of responsiveness

Negative Symptoms

Deficits in normal emotional and behavioral functioning:

- Flat Affect: Limited emotional expression

- Avolition: Lack of motivation

- Anhedonia: Inability to feel pleasure

- Social Withdrawal

Cognitive Symptoms

Dysfunction in memory, attention, and executive functions:

- Impaired Working Memory

- Reduced Attention Span

- Difficulty in Planning and Decision-Making

Primary Causes and Risk Factors

Psychiatric Disorders

- Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: Most common chronic condition associated with psychosis

- Bipolar Disorder: Psychosis during manic or depressive episodes

- Severe Depression: May result in psychotic depression, involving delusions of guilt or nihilism

- Schizoaffective Disorder: Blend of schizophrenia symptoms with mood disorder elements

Neurological and Medical Conditions

- Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

- Brain Tumors

- Autoimmune Encephalitis

- Dementia (e.g., Alzheimer’s Disease)

Substance-Induced Psychosis

- Illicit Drugs: LSD, methamphetamine, cocaine, and synthetic cannabinoids

- Prescription Medications: Corticosteroids, anticholinergics

- Alcohol Withdrawal (Delirium Tremens)

Psychosocial and Genetic Risk Factors

- Family history of psychotic disorders

- Childhood trauma and neglect

- Social isolation and chronic stress

- Migrant status and urban upbringing

Diagnostic Approach to Severe Psychosis

Timely diagnosis is essential for effective treatment planning. A structured diagnostic process includes:

Comprehensive Clinical Interview

- Timeline of symptom onset

- Substance use history

- Personal and family psychiatric background

Mental Status Examination

- Assessment of mood, affect, speech, thought content, insight, and judgment

Laboratory and Imaging Studies

- Toxicology Screen: Rule out substance-induced psychosis

- CBC, Electrolytes, LFTs, TSH: Identify metabolic or endocrine contributors

- MRI/CT Brain Scan: Exclude structural brain lesions

- EEG: Detect seizure activity or encephalopathy

Evidence-Based Treatment of Severe Psychosis

Acute Management Phase

Hospitalization is often necessary during the acute phase to ensure safety and initiate treatment.

Pharmacological Interventions

- Antipsychotics (First-line):

- First-Generation: Haloperidol, chlorpromazine

- Second-Generation: Risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, aripiprazole

- Adjunctive Agents:

- Benzodiazepines for acute agitation (e.g., lorazepam)

- Mood stabilizers (e.g., valproate, lithium) in bipolar disorder

- Clozapine: Reserved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia

Long-Term Maintenance Therapy

- Continuation of antipsychotic therapy to prevent relapse

- Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for patients with poor adherence

- Psychosocial support and occupational rehabilitation

Psychotherapeutic Approaches

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Psychosis (CBTp): Restructures distorted beliefs and improves coping

- Family Therapy: Reduces relapse by addressing dysfunctional dynamics

- Psychoeducation: Empowers patients and caregivers with illness insight

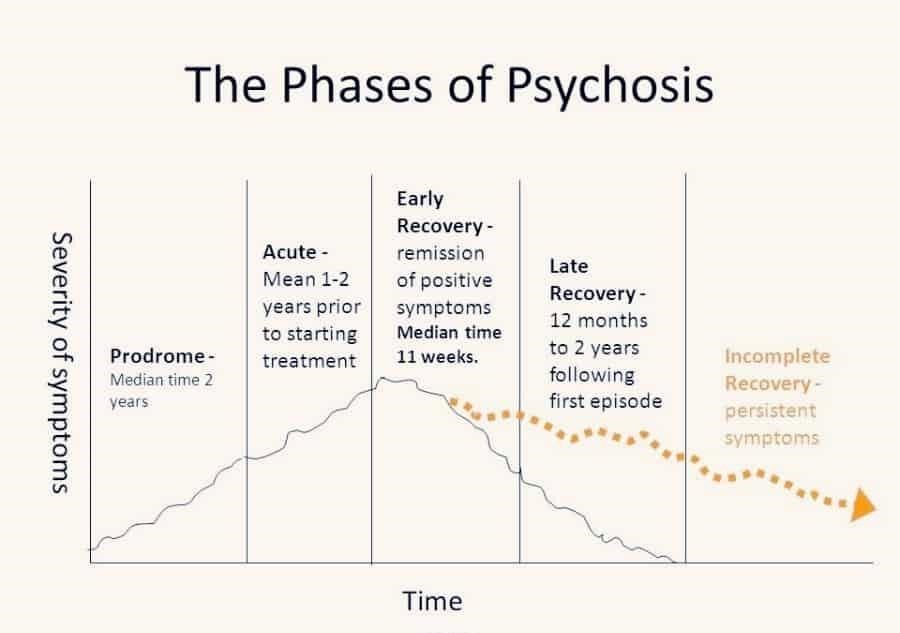

Prognosis and Recovery Trajectories

The outcome of severe psychosis varies depending on the underlying etiology, early intervention, and adherence to treatment. Factors contributing to a favorable prognosis include:

- Early and sustained treatment

- Good premorbid functioning

- Strong family and social support

- Absence of comorbid substance abuse

On the other hand, delayed treatment and recurrent psychotic episodes are linked to cognitive deterioration, functional impairment, and chronic disability.

Prevention and Relapse Mitigation

- Medication Adherence: Most critical factor in relapse prevention

- Monitoring Early Warning Signs: Sleep disruption, social withdrawal, and subtle thought disorganization

- Stress Reduction Techniques: Mindfulness, routine structure, support groups

- Integrated Care Models: Combining pharmacologic, psychotherapeutic, and social interventions

What are the early warning signs of severe psychosis?

Subtle cognitive changes, paranoia, social withdrawal, and sleep disturbances often precede a full-blown episode.

Can severe psychosis be cured?

While psychosis may not be curable in chronic conditions like schizophrenia, early and continuous treatment can lead to remission and functional recovery.

Is hospitalization always required?

Hospitalization is essential for acute cases where safety is compromised, or the patient lacks insight into their condition.

What role do family members play in recovery?

Family support and education significantly reduce relapse rates and improve treatment adherence and psychosocial outcomes.

How is psychosis different from schizophrenia?

Psychosis is a symptom or state; schizophrenia is a chronic mental disorder where psychosis is a defining feature.