Severe malaria is a life-threatening condition caused primarily by Plasmodium falciparum infection. It arises when parasitemia is extensive or when vital organ dysfunction occurs. Unlike uncomplicated malaria, severe malaria progresses rapidly, leading to high morbidity and mortality if not promptly diagnosed and treated. This form of malaria is a global health emergency, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, where transmission intensity is high and access to advanced care is limited.

Pathophysiology of Severe Malaria

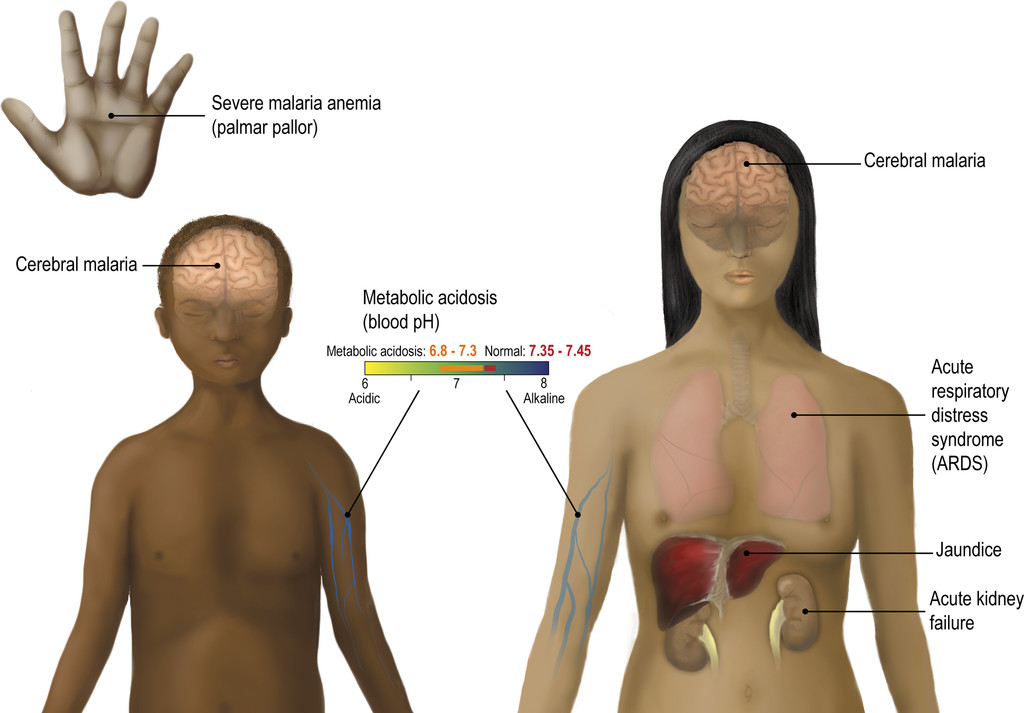

Severe malaria occurs when infected erythrocytes adhere to the endothelium of capillaries and post-capillary venules, leading to impaired microcirculatory flow, tissue hypoxia, and multiorgan dysfunction.

High-Risk Groups for Severe Malaria

- Children under 5 years in high transmission areas

- Pregnant women, particularly primigravidae

- Non-immune travelers from non-endemic regions

- Immunocompromised individuals including HIV-positive patients

- People with no prior exposure or incomplete prophylaxis

Key Clinical Manifestations

Severe malaria presents with signs of systemic illness. WHO criteria for severe malaria include:

Central Nervous System Involvement

- Cerebral malaria: unarousable coma lasting >30 minutes after seizure

- Convulsions: repeated generalized seizures

Hematologic Complications

- Severe anemia: hemoglobin <5 g/dL

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

Respiratory and Renal Symptoms

- Pulmonary edema or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Acute kidney injury (creatinine >3 mg/dL or urine output <0.5 mL/kg/hr)

Metabolic and Other Manifestations

- Hypoglycemia: blood glucose <40 mg/dL

- Lactic acidosis: pH <7.25 or lactate >5 mmol/L

- Hyperparasitemia: >10% of RBCs infected

Diagnostic Evaluation

Microscopic Confirmation

- Thick and thin blood smears: gold standard for species identification and parasitemia quantification

Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs)

- Detect Plasmodium falciparum-specific antigens (e.g., HRP2), useful in low-resource settings

Additional Laboratory Investigations

- Complete blood count: anemia, thrombocytopenia

- Renal and liver function tests

- Blood glucose and lactate levels

- Arterial blood gases

Complications of Severe Malaria

Severe malaria can progress rapidly and lead to fatal outcomes without intervention. Common complications include:

- Cerebral malaria: 15-20% mortality in children

- ARDS: often fatal without ventilation support

- Renal failure: may require dialysis

- Severe anemia: often necessitating transfusion

- Coagulopathy: spontaneous bleeding or DIC

- Hypoglycemia: worsened by quinine treatment

- Multiorgan failure: high fatality rate

Immediate Treatment Protocols

Antimalarial Therapy

Intravenous Artesunate is the first-line treatment recommended by WHO:

- Dose: 2.4 mg/kg IV at 0, 12, and 24 hours, then daily until oral therapy possible

- Transition to oral artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) after clinical improvement

Alternative (when artesunate is unavailable):

- Intravenous Quinine: loading dose followed by maintenance every 8 hours

- Close monitoring for QT prolongation and hypoglycemia is essential

Supportive Care

- Fluid resuscitation: careful to avoid pulmonary edema

- Blood transfusion: in severe anemia

- Renal support: dialysis for acute kidney injury

- Oxygen therapy or mechanical ventilation: for ARDS

- Glucose infusion: for hypoglycemia management

- Anticonvulsants: for seizures (e.g., diazepam or phenobarbital)

Prevention of Severe Malaria

Vector Control Measures

- Insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs)

- Indoor residual spraying (IRS)

- Mosquito repellent use

- Elimination of mosquito breeding sites

Chemoprophylaxis

- For travelers to endemic regions: atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline, or mefloquine

- For pregnant women in endemic zones: intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine

Vaccination

- RTS,S/AS01 (Mosquirix): approved for children in sub-Saharan Africa

- Ongoing development of next-generation vaccines (e.g., R21/Matrix-M)

Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

The prognosis of severe malaria depends on the timeliness of diagnosis and initiation of effective treatment. Delays of more than 24 hours are associated with significantly increased mortality. With prompt care, survival improves substantially, although neurological sequelae such as cognitive deficits may persist in cerebral malaria survivors, especially children.

Public Health and Global Burden

- Estimated 241 million cases and 627,000 deaths annually (WHO, latest report)

- 90%+ of deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa

- Malaria remains a leading cause of pediatric mortality in endemic regions

- Drug resistance and insecticide resistance threaten current control strategies

Severe malaria demands urgent recognition and aggressive intervention to prevent irreversible organ damage and death. Health systems in endemic regions must prioritize rapid diagnostics, consistent access to parenteral artesunate, and skilled critical care support. Preventive strategies—vector control, chemoprophylaxis, and emerging vaccines—are equally critical to reduce the incidence and burden of severe disease. Coordinated global action is essential to end malaria as a public health threat.