Serum sickness is a type III hypersensitivity reaction characterized by the formation of immune complexes following exposure to foreign proteins or antigens, typically introduced through certain medications, antitoxins, or infections. These immune complexes deposit in tissues, triggering systemic inflammation and vascular injury. Though historically associated with animal-derived antiserum therapies, modern cases are more often linked to drugs, such as monoclonal antibodies and antibiotics.

Pathophysiology of Serum Sickness

Serum sickness is mediated by immune complex formation. Upon exposure to a foreign protein or antigen, the body produces antibodies. The interaction between antigens and antibodies forms circulating immune complexes that deposit in small vessels and tissues, leading to complement activation and inflammation.

Common Triggers and Risk Factors

Medications

- Monoclonal antibodies (e.g., rituximab, infliximab)

- Antibiotics (e.g., cefaclor, penicillin, sulfonamides)

- Non-human antiserum (e.g., equine antitoxins for botulism or rabies)

- Allopurinol, phenytoin, and carbamazepine

Infections

- Viral hepatitis

- Epstein-Barr virus

- Streptococcal infections

Individual Susceptibility

- Genetic predisposition to hypersensitivity

- Autoimmune conditions

- High antigen load or repeated exposures

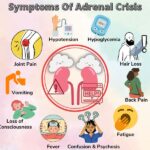

Clinical Presentation of Serum Sickness

Symptoms typically appear 7–14 days after exposure to the offending agent and include:

- Fever and malaise

- Urticarial or morbilliform rash

- Polyarthralgia or arthritis (particularly in knees, wrists, and ankles)

- Lymphadenopathy

- Myalgia and fatigue

- Facial or limb edema

- Gastrointestinal disturbances (nausea, abdominal pain)

In severe cases, systemic involvement such as nephritis, myocarditis, or neurologic symptoms may occur.

Diagnostic Criteria and Laboratory Investigations

Clinical Diagnosis

Diagnosis is largely clinical, based on symptom pattern and timing after exposure. A thorough history of recent drug use or serum therapy is critical.

Laboratory Findings

- Leukocytosis or leukopenia

- Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Hypocomplementemia (especially low C3 and C4)

- Proteinuria or hematuria in renal involvement

- Positive rheumatoid factor or ANA in some cases

Differential diagnosis should rule out lupus, viral exanthems, acute rheumatic fever, and drug eruptions.

Treatment of Serum Sickness

Discontinuation of Offending Agent

The cornerstone of treatment is immediate withdrawal of the triggering substance. In most cases, symptoms begin to resolve within 48–72 hours of discontinuation.

Symptomatic Management

- Antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine or cetirizine) for pruritus and rash

- NSAIDs for fever and joint pain

- Corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) in moderate to severe cases or with organ involvement

Severe or Refractory Cases

- High-dose systemic corticosteroids

- Hospitalization for supportive care and monitoring

- Plasmapheresis in cases with life-threatening complications (e.g., renal failure or vasculitis)

Prognosis and Outcomes

Serum sickness is typically self-limiting with full recovery within 1–2 weeks following appropriate management. Complications are rare but can include:

- Persistent renal involvement (proteinuria or nephritis)

- Chronic arthralgia

- Vasculitis

Recurrence is possible with re-exposure to the same or cross-reactive agents.

Prevention Strategies for Serum Sickness

- Avoid repeated exposure to known triggering agents

- Use humanized or fully human monoclonal antibodies when possible

- Pre-treatment skin testing for high-risk antitoxins

- Desensitization protocols in unavoidable therapeutic cases

Serum Sickness vs. Serum Sickness-Like Reactions (SSLR)

It is important to distinguish serum sickness from SSLRs, which mimic the clinical presentation but lack immune complex formation and complement consumption. SSLRs are usually associated with cefaclor and are limited to rash, fever, and arthralgia, without organ involvement.

Serum sickness is a type III hypersensitivity reaction marked by systemic inflammation following exposure to foreign antigens. While now rare due to modern biologics and improved therapeutic protocols, awareness and timely management remain critical. Identifying causative agents, managing symptoms, and avoiding recurrence are key components in ensuring patient safety and optimal outcomes.