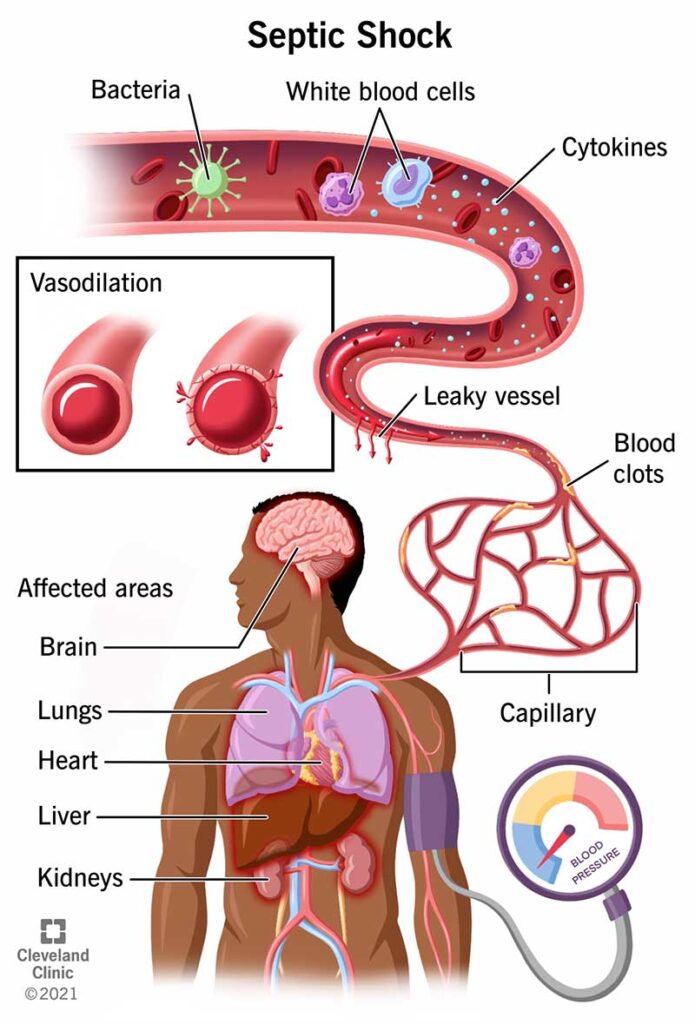

Septic shock is a critical, life-threatening condition that results from a severe infection leading to dangerously low blood pressure and organ failure. It is the most severe manifestation of sepsis, characterized by profound circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities. Early diagnosis and aggressive intervention are vital to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Pathophysiology of Septic Shock

Septic shock occurs when a systemic infection triggers an overwhelming immune response. This cascade leads to widespread inflammation, increased capillary permeability, vasodilation, and impaired tissue oxygenation.

Key mechanisms include:

- Endothelial damage

- Dysregulated coagulation

- Mitochondrial dysfunction

- Cellular apoptosis

Common Causes of Septic Shock

Septic shock can originate from any bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic infection. The most frequent sources include:

- Pneumonia – Respiratory tract infections are the leading cause.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) – Especially in the elderly.

- Abdominal infections – Such as perforated bowel or peritonitis.

- Skin infections – Including cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.

- Device-related infections – Catheters, ventilators, or central lines.

Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli) and Gram-positive organisms (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus) are the predominant pathogens.

Recognizing Septic Shock Symptoms

Timely identification of septic shock is critical. Key clinical features include:

- Persistent hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation

- Elevated lactate levels (>2 mmol/L), indicating tissue hypoperfusion

- Altered mental status

- Rapid heart rate (tachycardia)

- Fever or hypothermia

- Cold, clammy extremities

- Decreased urine output (<0.5 mL/kg/hr)

Diagnostic Approach

Accurate diagnosis involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory investigations:

- Blood cultures before antibiotics

- Complete blood count (CBC) showing leukocytosis or leukopenia

- Serum lactate levels for perfusion assessment

- Procalcitonin as a sepsis marker

- Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis

- Imaging studies (CT, ultrasound, X-ray) to identify infection source

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) and qSOFA scores help assess severity and predict outcomes.

Management and Treatment of Septic Shock

Initial Resuscitation

Management must begin immediately within the first hour:

- IV fluid resuscitation: Crystalloids (30 mL/kg within 3 hours)

- Vasopressors: Norepinephrine is first-line for MAP <65 mmHg

- Blood cultures and antibiotics: Administer broad-spectrum antimicrobials early

Antimicrobial Therapy

Empiric antibiotics must be tailored based on:

- Infection source

- Patient history

- Local antibiogram data

Common regimens include:

- Piperacillin-tazobactam

- Cefepime

- Vancomycin

- Carbapenems (for resistant pathogens)

Hemodynamic Support

- Vasopressors: Norepinephrine > dopamine; add vasopressin if needed

- Inotropes: Dobutamine for myocardial dysfunction

- Corticosteroids: Hydrocortisone 200 mg/day for refractory shock

Supportive ICU Care

- Mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure

- Renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury

- Nutritional support via enteral feeding

- Glycemic control (target blood glucose <180 mg/dL)

Complications of Septic Shock

Septic shock may lead to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) and death. Major complications include:

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Acute kidney injury (AKI)

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Myocardial depression

- Liver dysfunction

- Secondary infections from prolonged ICU stay

Prognosis and Mortality Rates

Despite advancements, septic shock has a high mortality rate, ranging from 30% to over 50% in severe cases. Prognosis depends on:

- Time to antibiotic initiation

- Patient’s baseline health

- Organ function at admission

- Source control effectiveness

Early goal-directed therapy has shown to improve outcomes, especially when implemented within the golden first hour.

Prevention of Septic Shock

Preventive strategies are crucial and include:

- Vaccination against pneumococcus, influenza, and meningococcus

- Infection control protocols in hospitals

- Aseptic technique during catheter or line insertions

- Prompt treatment of localized infections

- Monitoring high-risk patients closely (elderly, immunocompromised)

Public and healthcare provider awareness is key in reducing incidence and improving early recognition.

Septic shock is a dire medical emergency requiring immediate recognition and aggressive, multidisciplinary management. With timely interventions, mortality can be significantly reduced. Continuous advancements in critical care practices, early diagnostic tools, and personalized antimicrobial therapies are essential to improve survival rates.