Reflux esophagitis is a subtype of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) characterized by inflammation, irritation, or swelling of the esophageal lining due to repeated exposure to stomach acid. Chronic reflux leads to mucosal damage, predisposing patients to complications such as strictures, Barrett’s esophagus, and even esophageal carcinoma if left untreated.

Causes of Reflux Esophagitis

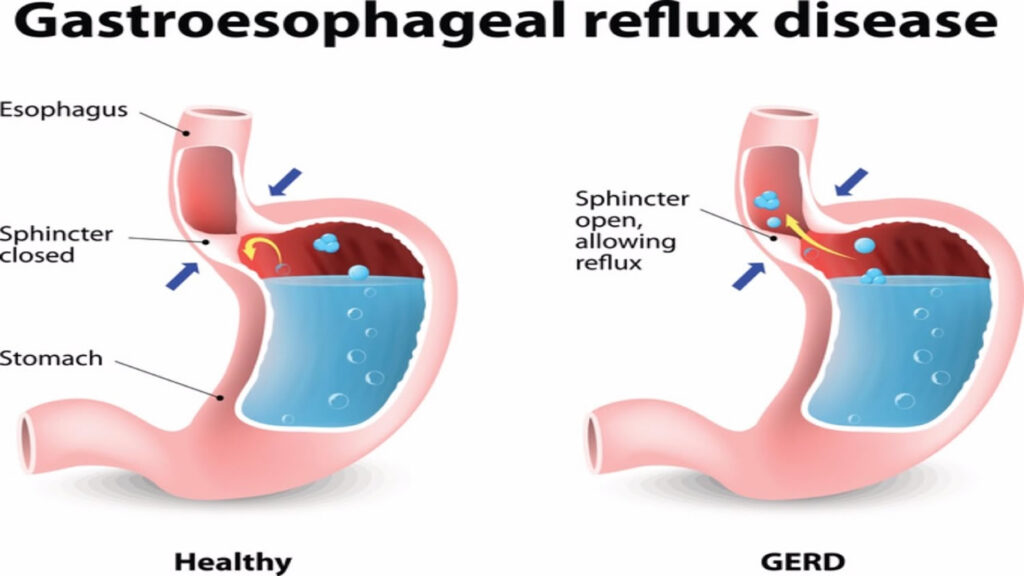

The primary etiology of reflux esophagitis is the malfunction of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), allowing gastric contents to reflux into the esophagus. Several contributing factors include:

- Hiatal Hernia: Weakens the LES by altering the pressure dynamics between the thorax and abdomen.

- Obesity: Increases intra-abdominal pressure, promoting reflux.

- Pregnancy: Hormonal changes and mechanical pressure contribute to sphincter relaxation.

- Medications: Calcium channel blockers, anticholinergics, and sedatives can reduce LES tone.

- Diet and Lifestyle: Spicy foods, caffeine, alcohol, smoking, and overeating exacerbate reflux.

Recognizing Symptoms of Reflux Esophagitis

Early identification of symptoms ensures timely intervention and prevents progression. The most common clinical manifestations include:

- Heartburn: A burning sensation behind the sternum, often worse after meals or when lying down.

- Regurgitation: The sensation of acid backing up into the throat or mouth.

- Dysphagia: Difficulty swallowing due to esophageal narrowing or inflammation.

- Odynophagia: Painful swallowing indicating severe mucosal injury.

- Chronic Cough and Hoarseness: Result from acid irritation of the larynx.

Persistent symptoms warrant further investigation to confirm the diagnosis and rule out severe complications.

Diagnosing Reflux Esophagitis

A thorough diagnostic approach ensures accurate assessment and targeted therapy.

Upper Endoscopy (Esophagogastroduodenoscopy)

Endoscopic examination remains the gold standard for diagnosing reflux esophagitis. It allows direct visualization of mucosal damage, ulcerations, and the presence of Barrett’s esophagus. Biopsies are often obtained to assess for dysplasia or malignancy.

Esophageal pH Monitoring

Ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring quantifies acid exposure within the esophagus and correlates symptoms with acid reflux events, aiding in the diagnosis of atypical presentations.

Esophageal Manometry

Manometry assesses esophageal motility and LES function, crucial for differentiating primary esophageal motility disorders from reflux-induced changes.

Grading the Severity of Reflux Esophagitis

The Los Angeles (LA) Classification System is widely used to categorize the severity of mucosal damage:

- Grade A: One or more mucosal breaks ≤5 mm.

- Grade B: Mucosal breaks >5 mm but non-contiguous.

- Grade C: Mucosal breaks continuous between mucosal folds but involving less than 75% of the circumference.

- Grade D: Mucosal breaks involving at least 75% of the esophageal circumference.

Accurate grading informs treatment intensity and monitoring intervals.

Management Strategies for Reflux Esophagitis

Lifestyle and Dietary Modifications

Behavioral interventions form the cornerstone of management:

- Weight reduction for overweight individuals.

- Elevating the head of the bed during sleep.

- Avoiding late-night meals and foods that trigger reflux.

- Smoking cessation and limiting alcohol intake.

Pharmacological Therapy

Pharmacologic treatment aims to reduce gastric acidity and promote mucosal healing.

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): The first-line therapy; drugs such as omeprazole, esomeprazole, and pantoprazole effectively heal mucosal injury.

- Histamine-2 Receptor Antagonists (H2RAs): Alternatives or adjuncts for mild to moderate disease.

- Antacids and Alginates: Offer symptomatic relief but do not heal esophagitis.

Long-term PPI therapy is indicated for severe cases or those with complications like Barrett’s esophagus.

Endoscopic and Surgical Interventions

When medical management fails or complications arise, procedural interventions may be necessary:

- Nissen Fundoplication: Laparoscopic surgical technique that reinforces the LES by wrapping the gastric fundus around the lower esophagus.

- Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication (TIF): A less invasive endoscopic alternative.

- Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation: The LINX device provides dynamic LES reinforcement.

Surgical options are especially relevant for young patients seeking alternatives to lifelong medication.

Complications Associated with Reflux Esophagitis

Chronic inflammation can lead to serious complications:

- Esophageal Stricture: Fibrotic narrowing resulting in dysphagia.

- Barrett’s Esophagus: Metaplastic transformation of esophageal epithelium, increasing the risk of adenocarcinoma.

- Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: A life-threatening malignancy arising from Barrett’s esophagus.

Regular surveillance endoscopies are recommended for high-risk individuals.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

With appropriate therapy, most cases of reflux esophagitis achieve complete mucosal healing and symptom resolution. However, untreated or poorly controlled reflux can lead to progressive disease and increased morbidity. Early intervention, patient education, and individualized treatment plans are crucial to optimizing long-term outcomes.

Reflux esophagitis represents a significant clinical burden but is highly manageable with prompt diagnosis, tailored pharmacologic therapy, lifestyle interventions, and, when necessary, surgical solutions. A comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach ensures sustained symptom control, mucosal healing, and prevention of serious complications.