Pseudomonas aeruginosa urinary tract infections (UTIs) represent a challenging and often persistent form of gram-negative bacteriuria, particularly prevalent in hospital settings. Known for its resistance to multiple antibiotic classes and ability to form resilient biofilms, P. aeruginosa UTIs are primarily associated with catheter use and immunocompromised states, requiring prompt identification and targeted management.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Pseudomonas UTIs

While Escherichia coli remains the most common UTI pathogen, P. aeruginosa is increasingly implicated in healthcare-associated and complicated UTIs. Key risk factors include:

- Indwelling urinary catheters or recent catheterization

- Recurrent or prolonged hospitalization

- Urologic instrumentation or surgery

- Structural abnormalities of the urinary tract

- Diabetes mellitus and immunosuppression

- Long-term care facility residence

- Prior or repeated exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics

Pathogenesis and Transmission Dynamics

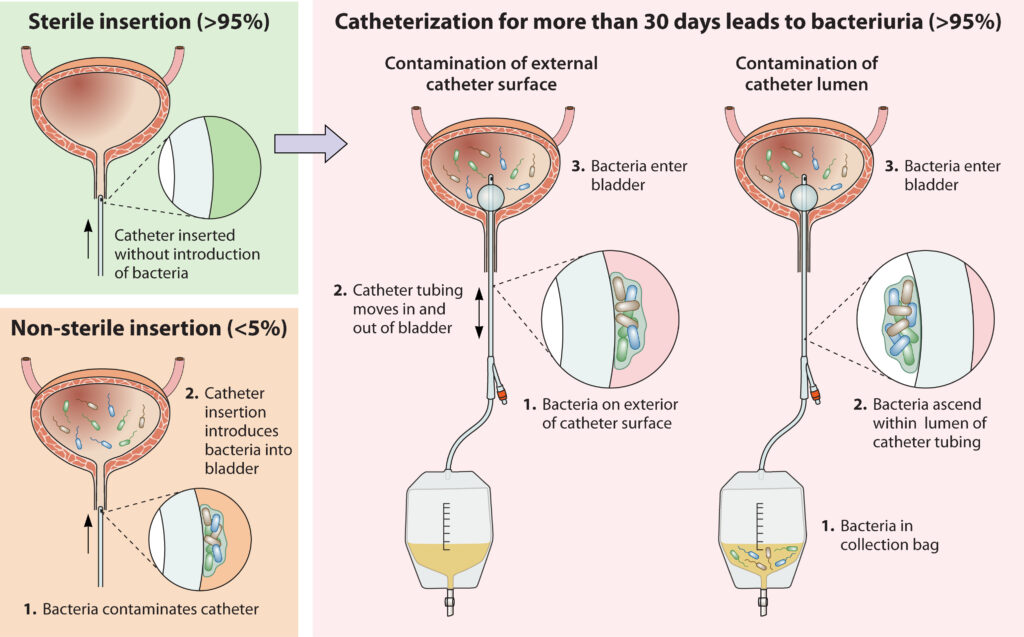

Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonizes moist environments, including hospital equipment, sinks, and catheters. Infection typically follows ascending colonization of the urinary tract, particularly in patients with compromised uroepithelial defenses.

Infection Progression Flow

The pathogen’s ability to form biofilms on catheter surfaces makes eradication difficult and contributes to persistence and relapse.

Clinical Manifestations of Pseudomonas Urinary Tract Infection

Symptoms vary depending on the extent and site of infection:

Lower Urinary Tract (Cystitis)

- Dysuria

- Urinary frequency and urgency

- Suprapubic pain

- Foul-smelling or cloudy urine

Upper Urinary Tract (Pyelonephritis)

- Flank pain

- Fever and chills

- Nausea and vomiting

- Systemic signs such as elevated white cell count

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is also common, particularly in catheterized patients.

Diagnostic Evaluation of Pseudomonas UTI

Urinalysis and Culture

- Pyuria, bacteriuria, and positive nitrites (although nitrites may be negative in non-nitrate-reducing bacteria)

- Definitive diagnosis is made via urine culture, with colony counts >10⁵ CFU/mL typically considered significant in symptomatic patients

- Species identification and antibiotic susceptibility testing are essential due to frequent resistance

Imaging Studies

- Recommended in cases of recurrent infection, suspected obstruction, or complicated pyelonephritis

- Ultrasound or CT may reveal hydronephrosis or abscess formation

Antibiotic Treatment of Pseudomonas UTIs

Treatment must be guided by local antibiograms and individual susceptibility profiles due to the high prevalence of multidrug resistance.

Empirical Therapy (High-Risk or Critically Ill)

- Piperacillin-tazobactam

- Ceftazidime or cefepime

- Meropenem or imipenem-cilastatin

- Consider adding aminoglycosides (e.g., amikacin) in critically ill patients

Definitive Therapy (Based on Sensitivities)

- Oral ciprofloxacin (if susceptible and non-severe)

- Extended-spectrum beta-lactams for resistant strains

- Novel agents like ceftolozane-tazobactam or ceftazidime-avibactam for carbapenem-resistant isolates

Duration ranges from 7 to 14 days depending on infection severity, response, and immune status.

Complications and Prognosis

Without adequate treatment, P. aeruginosa UTIs may progress to:

- Pyelonephritis with renal abscess

- Bacteremia and sepsis

- Renal scarring and chronic kidney disease

- Urosepsis, particularly in high-risk individuals

Mortality increases with delayed treatment, inappropriate antibiotic use, and invasive urologic interventions.

Infection Control and Prevention Strategies

Catheter Management

- Avoid unnecessary catheterization

- Use aseptic insertion and maintenance techniques

- Prompt removal when no longer indicated

- Use of antimicrobial-impregnated catheters in high-risk settings

Antimicrobial Stewardship

- Limit use of broad-spectrum antibiotics to reduce resistance development

- De-escalate therapy based on culture results

- Monitor local resistance trends and update empirical protocols accordingly

Biofilm Formation and Its Clinical Implications

Biofilm production by P. aeruginosa contributes to:

- Chronic infection

- Reduced antibiotic penetration

- Increased resistance to host defenses

Research continues into anti-biofilm agents and surface-modified catheters to mitigate this effect.

Emerging Therapeutics and Resistance Patterns

With increasing prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) and carbapenemase-producing strains, alternative therapies include:

- Fosfomycin (intravenous formulation)

- Combination regimens including colistin, tigecycline, or plazomicin

- Phage therapy (experimental stage)

- Inhibitors targeting quorum sensing and biofilm disruption

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q1. Is Pseudomonas aeruginosa a common cause of UTIs?

It is less common than E. coli but frequently causes complicated and healthcare-associated UTIs.

Q2. Can a Pseudomonas UTI go away on its own?

Unlikely. Treatment is required, especially due to its drug resistance and potential to cause upper tract involvement.

Q3. What antibiotics work against Pseudomonas in urine?

Ciprofloxacin, ceftazidime, meropenem, or piperacillin-tazobactam—based on culture sensitivity.

Q4. How is a catheter-associated UTI from Pseudomonas prevented?

Through strict catheter protocols, limiting use, and ensuring proper hygiene during insertion and maintenance.

Q5. What makes Pseudomonas harder to treat than other UTI pathogens?

Its intrinsic resistance mechanisms, ability to form biofilms, and capacity for genetic adaptation in hospital environments.