Pseudomonas aeruginosa peritonitis represents a severe and potentially life-threatening intra-abdominal infection, particularly prevalent in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis (PD). Due to its intrinsic resistance mechanisms and capacity to form biofilms, this gram-negative pathogen poses substantial treatment hurdles and increases the risk of technique failure, catheter loss, and transition to hemodialysis.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

While gram-positive organisms remain the most frequent causes of peritonitis in PD patients, Pseudomonas aeruginosa accounts for 5–15% of culture-positive cases, often linked to:

- Improper exchange technique or hygiene lapses

- Exit-site or tunnel infections

- Prior antibiotic exposure altering microbiota

- Hospital-acquired colonization

- Immunocompromised states

Pathophysiology and Infection Dynamics

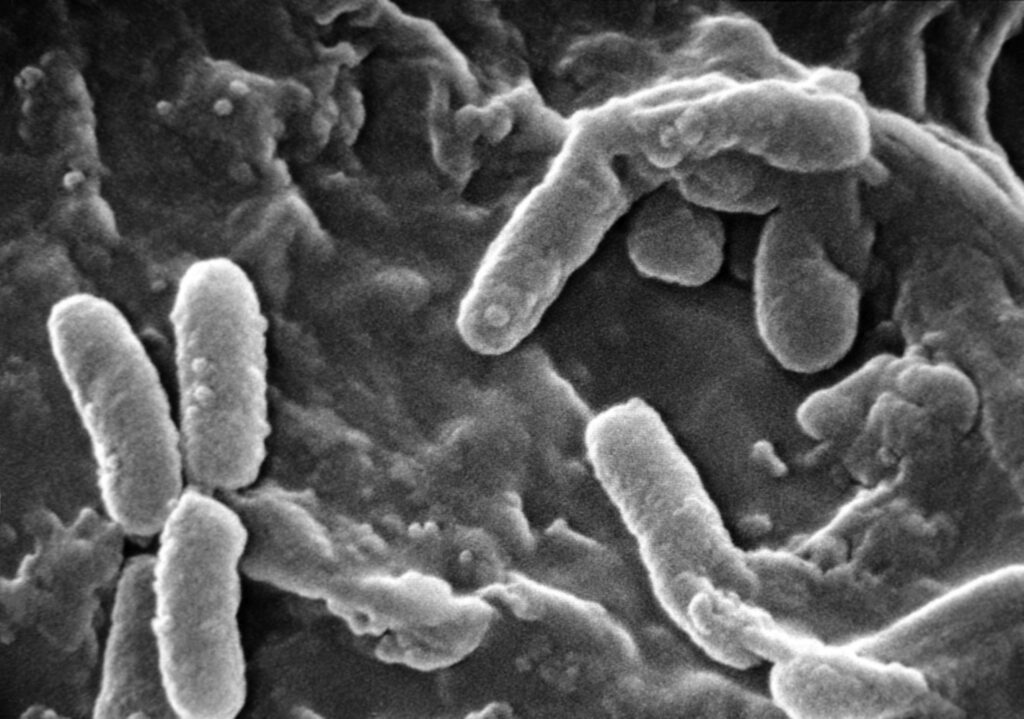

The peritoneal cavity becomes infected when P. aeruginosa breaches sterile barriers—either through translocation, catheter contamination, or hematogenous spread. Once inside, it adheres to the peritoneal lining and plastic surfaces, initiating biofilm formation that facilitates chronic infection and resistance.

Clinical Presentation of Pseudomonas Peritonitis

Patients typically exhibit acute signs of peritoneal inflammation. The hallmark clinical features include:

- Abdominal pain and tenderness

- Cloudy peritoneal effluent

- Fever and malaise

- Nausea or vomiting

- Sometimes associated with tunnel or exit-site infection

In immunosuppressed or elderly patients, symptoms may be subtler, necessitating a high index of suspicion.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Laboratory Testing

- Peritoneal effluent analysis:

- WBC count >100 cells/µL, with >50% neutrophils

- Gram stain: may reveal gram-negative rods

- Culture: definitive identification using automated systems or molecular assays

- Blood cultures: To detect bacteremia in severe cases

- CRP and procalcitonin: Support systemic inflammatory response assessment

Imaging

Ultrasound or CT imaging may assist in evaluating for intra-abdominal abscesses or catheter-related complications, especially in refractory or relapsing infections.

Antimicrobial Therapy and Resistance Management

Empiric Treatment

Initial empiric coverage must include agents active against gram-negative organisms. Recommended intraperitoneal (IP) regimens include:

- Ceftazidime or cefepime

- Aminoglycosides (e.g., tobramycin)

- Piperacillin-tazobactam in select settings

- Consider vancomycin if mixed infection suspected

Tailored Therapy Based on Sensitivity

Upon culture confirmation of P. aeruginosa, therapy should be optimized:

- Dual-agent therapy is typically necessary to prevent resistance emergence

- Duration: at least 21 days, depending on clinical response

- Avoid monotherapy with fluoroquinolones unless susceptibility is confirmed

Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms

P. aeruginosa displays multiple resistance pathways:

- Efflux pump overexpression

- AmpC beta-lactamase induction

- Biofilm-mediated protection

- Outer membrane porin loss

These mechanisms necessitate aggressive, targeted, and often combination therapies.

Catheter Management in Pseudomonas Peritonitis

Catheter removal is frequently required due to the high risk of biofilm persistence and treatment failure.

Indications for catheter removal:

- Persistent positive cultures after 5 days of therapy

- Relapsing peritonitis

- Concurrent tunnel or exit-site infections

- Clinical deterioration despite antibiotics

In some cases, catheter exchange over a guidewire may be attempted, though definitive removal is often preferred for infection control.

Outcomes and Complications

Without prompt and effective intervention, P. aeruginosa peritonitis can lead to:

- Peritoneal membrane failure

- Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis

- Septicemia and multi-organ involvement

- Permanent switch to hemodialysis

Despite aggressive treatment, technique failure rates exceed 40–50%, particularly when biofilms are established or resistant strains are involved.

Preventive Strategies

To minimize infection risk:

- Strict adherence to sterile PD exchange protocols

- Routine monitoring of exit-site health

- Prophylactic topical antibiotics (e.g., mupirocin) at exit site

- Timely treatment of preceding tunnel or soft tissue infections

- Education and retraining of patients and caregivers

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q1. What makes Pseudomonas peritonitis more challenging than other types?

Its resistance profile, ability to form biofilms, and association with catheter colonization make it difficult to eradicate with antibiotics alone.

Q2. Can Pseudomonas peritonitis be treated without catheter removal?

Occasionally, yes—if identified early and responding well to dual antibiotic therapy—but most cases ultimately require catheter removal.

Q3. What is the typical duration of treatment for Pseudomonas peritonitis?

At least 21 days of tailored intraperitoneal antibiotic therapy, extended in complex or resistant infections.

Q4. Is there a way to prevent Pseudomonas peritonitis in PD patients?

Yes—strict aseptic technique, exit-site care, and prophylactic measures can significantly reduce incidence.

Q5. What role does biofilm play in treatment failure?

Biofilms shield bacteria from immune cells and antibiotics, promoting persistence and relapse even after initial clinical improvement.