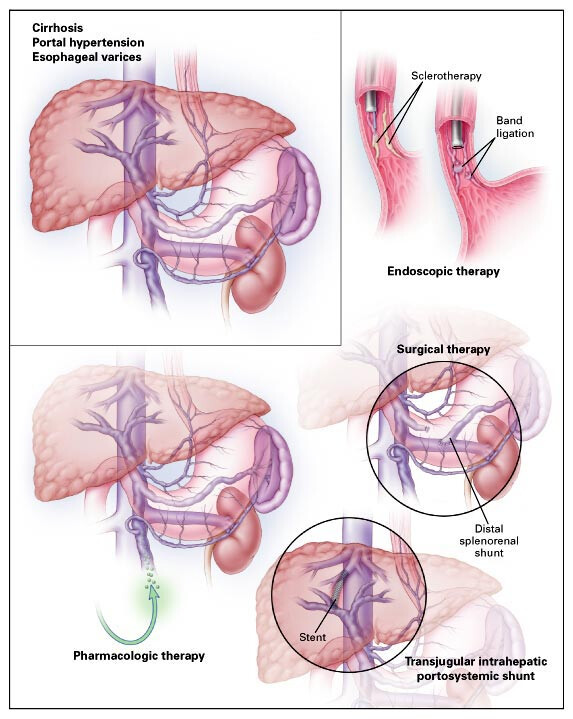

Bleeding from esophageal varices remains one of the most life-threatening complications of portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Preventive strategies, both pharmacological and procedural, are essential to reduce the risk of first-time and recurrent variceal hemorrhage, thereby improving survival and long-term outcomes.

Understanding Esophageal Varices and Their Bleeding Risk

Esophageal varices are dilated submucosal veins in the lower esophagus resulting from elevated pressure in the portal venous system, typically due to liver cirrhosis. These vessels are prone to rupture, leading to massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Pathophysiology of Variceal Formation

- Chronic liver injury → Cirrhosis → Increased intrahepatic resistance

- Portal hypertension → Development of collateral circulation

- Varices form in esophagus, stomach, and rectum

- Elevated portal pressure (>12 mmHg) → High risk of rupture

Non-Selective Beta-Blockers for Primary Prevention

Non-selective beta-blockers (NSBBs) are the cornerstone of primary prophylaxis against first variceal bleeding in patients with medium or large varices.

Mechanism of Action

- Decrease cardiac output (β1-blockade)

- Splanchnic vasoconstriction reduces portal blood flow (β2-blockade)

- Portal pressure reduction minimizes bleeding risk

Recommended Medications

| Drug | Initial Dose | Target Dose |

|---|---|---|

| Propranolol | 20 mg twice daily | Adjust to reduce resting heart rate by 25% or to 55–60 bpm |

| Nadolol | 40 mg once daily | Titrate to similar targets |

Indication:

- Medium to large varices with high-risk stigmata (e.g., red wale marks)

- Child-Pugh class B or C cirrhosis

Endoscopic Variceal Ligation (EVL): A Procedural Approach

Endoscopic variceal ligation is an effective, evidence-backed method to mechanically obliterate esophageal varices.

Procedure Overview

- Involves placement of rubber bands over varices during endoscopy

- Leads to thrombosis and fibrosis of varices

- Reduces size and risk of bleeding

Clinical Use

- Alternative to beta-blockers when contraindicated or not tolerated

- Combined with beta-blockers in some high-risk patients

- Preferred for patients with large varices and history of intolerance to medical therapy

Follow-Up

- Repeat EVL every 2–4 weeks until variceal obliteration

- Surveillance endoscopy every 6–12 months thereafter

Prevention of Rebleeding (Secondary Prophylaxis)

Patients who have recovered from an initial variceal hemorrhage are at extremely high risk of recurrence without appropriate secondary prevention.

Combined Therapy

- Non-selective beta-blockers + EVL is the standard of care

- Reduces rebleeding rates by 30–40%

- Improves survival compared to either therapy alone

Other Medical Options

- Isosorbide mononitrate (added in select cases for portal pressure reduction)

- Avoid monotherapy with nitrates due to side effects and lower efficacy

Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) for Refractory Cases

TIPS is a radiologic procedure that creates a shunt between the portal and hepatic veins to decompress the portal system.

Indications

- Refractory variceal bleeding unresponsive to combined therapy

- Early use (within 72 hours) in high-risk patients (Child-Pugh C <14 or HVPG ≥20 mmHg)

Risks and Considerations

- Encephalopathy occurs in 30–40% of patients post-TIPS

- Shunt dysfunction may require revision

- Best used selectively in specialized centers

Surveillance and Risk Stratification for Bleeding Prevention

Regular surveillance endoscopy and non-invasive risk assessment guide individualized prevention strategies.

Surveillance Recommendations

| Stage | Surveillance Interval |

|---|---|

| No varices (compensated cirrhosis) | Every 2–3 years |

| Small varices without risk signs | Every 1–2 years |

| After EVL or bleeding episode | Every 6–12 months |

Non-Endoscopic Tools

- Transient elastography (FibroScan): Measures liver stiffness, correlates with portal pressure

- Platelet count <150,000/mm³ + liver stiffness >20 kPa: Predictive of varices

- May reduce need for initial endoscopy in selected cases

Lifestyle Modifications and Etiological Management

Addressing the root cause of liver disease and adopting lifestyle changes are crucial components in long-term variceal management.

Alcohol and Hepatitis Management

- Complete alcohol cessation is vital in alcoholic cirrhosis

- Antiviral therapy for HBV and HCV reduces portal pressure over time

Nutritional Support

- Ensure adequate protein intake to avoid sarcopenia

- Monitor for zinc, vitamin D, and B-complex deficiencies

Weight and Comorbidity Control

- Manage obesity and diabetes in NASH-related cirrhosis

- Avoid hepatotoxic medications and herbal supplements

Preventing bleeding from esophageal varices demands a structured, multifaceted approach. Through risk stratification, effective use of beta-blockers, strategic deployment of endoscopic interventions, and judicious consideration of TIPS, clinicians can significantly mitigate the life-threatening consequences of variceal hemorrhage. Early intervention, surveillance, and addressing underlying liver disease etiology remain paramount to long-term patient survival and quality of life.Bleeding from esophageal varices remains one of the most life-threatening complications of portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Preventive strategies, both pharmacological and procedural, are essential to reduce the risk of first-time and recurrent variceal hemorrhage, thereby improving survival and long-term outcomes.