Postoperative acute pain is a common, expected physiological response following surgical intervention. It typically arises within hours after surgery and lasts up to 7 days, though it may persist longer depending on the procedure and individual response. This pain is primarily nociceptive and results from tissue injury, inflammation, and the activation of pain pathways.

Failure to manage postoperative acute pain effectively can lead to adverse outcomes including delayed recovery, increased risk of complications, development of chronic pain, and heightened patient anxiety. A strategic, evidence-based approach is essential for improving postoperative outcomes and enhancing patient satisfaction.

Etiology and Mechanisms of Postoperative Pain

Surgical Tissue Injury and Inflammatory Response

The fundamental cause of postoperative pain is the activation of nociceptors in response to mechanical tissue disruption, chemical irritation, and inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins, bradykinin, and cytokines. These signals are transmitted to the central nervous system, where they are interpreted as pain.

Types of Pain Involved

- Somatic pain: Sharp, well-localized pain from skin, muscles, and soft tissues.

- Visceral pain: Dull, diffuse pain originating from internal organs.

- Neuropathic pain: May result from nerve injury during surgery and is characterized by burning or shooting sensations.

Classification of Postoperative Pain Intensity

Pain severity varies by procedure, with higher intensities seen in orthopedic, thoracic, and abdominal surgeries. Pain scales such as the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) are employed to quantify pain and guide treatment.

Multimodal Analgesia: Gold Standard for Postoperative Pain Management

Multimodal analgesia combines agents and techniques that target different pain pathways to enhance analgesic efficacy while minimizing side effects.

Pharmacologic Strategies

1. Non-Opioid Analgesics

- Acetaminophen: Central analgesic with minimal side effects, often used as baseline therapy.

- NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen, ketorolac): Effective anti-inflammatory agents but contraindicated in renal impairment or bleeding risk.

2. Opioids

Used for moderate to severe pain; include morphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone. While effective, opioids carry risks of respiratory depression, nausea, constipation, and dependency.

3. Adjuvant Medications

- Gabapentinoids (gabapentin, pregabalin): Useful for neuropathic pain.

- Ketamine: NMDA receptor antagonist that provides opioid-sparing effects.

- Dexmedetomidine and clonidine: Alpha-2 agonists with sedative and analgesic properties.

Regional and Local Anesthesia Techniques

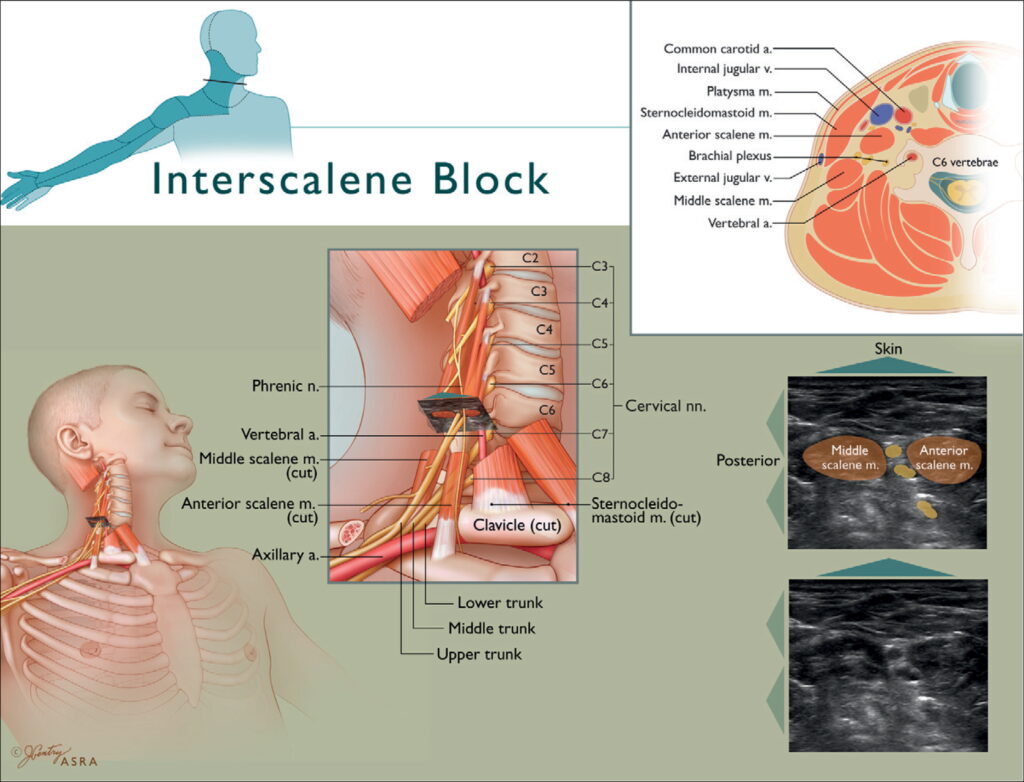

1. Peripheral Nerve Blocks

- Single-shot or continuous infusion of local anesthetic at nerve plexuses (e.g., femoral, brachial plexus blocks).

2. Epidural Analgesia

Common in thoracic and abdominal surgeries; delivers anesthetic directly into the epidural space for prolonged relief.

3. Wound Infiltration and Local Anesthetics

Direct application of local anesthetic to the surgical site can reduce early postoperative pain.

Non-Pharmacologic Pain Management Approaches

Complementary methods are effective adjuncts in a holistic pain management plan:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

- Acupuncture

- Patient education and expectation setting

- Cryotherapy and heat therapy

These interventions can reduce the perception of pain and promote quicker recovery.

Monitoring and Pain Assessment

Regular and systematic pain assessment is crucial for ensuring adequate pain relief and preventing complications. Key tools include:

- Numerical Rating Scale (NRS)

- Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

- Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) for non-verbal or sedated patients

Pain assessments must be recorded at regular intervals and post-intervention to gauge treatment efficacy.

Managing Special Populations

Pediatric Patients

Children may express pain differently and benefit from age-appropriate pain scales (e.g., FLACC, Wong-Baker Faces) and caregiver involvement.

Elderly Patients

Age-related pharmacokinetic changes and comorbidities necessitate cautious drug selection and lower dosages to avoid toxicity.

Opioid-Tolerant Individuals

Patients on chronic opioid therapy may require higher dosages or alternative analgesic plans involving ketamine or regional blocks.

Potential Complications of Inadequate Pain Control

- Delayed ambulation and pulmonary complications

- Thromboembolism due to immobility

- Impaired wound healing

- Persistent postsurgical pain (chronic pain transition)

- Psychological distress (anxiety, depression)

Effective pain control not only improves comfort but also contributes to reduced hospital stays and healthcare costs.

Optimizing Outcomes Through Individualized Pain Management

The management of postoperative acute pain must be proactive, multimodal, and tailored to each patient. By combining pharmacologic agents with regional anesthesia and supportive therapies, we can achieve superior pain relief, minimize side effects, and foster faster recovery. Integrating pain management into surgical care pathways ensures that optimal outcomes are consistently achieved for diverse patient populations.