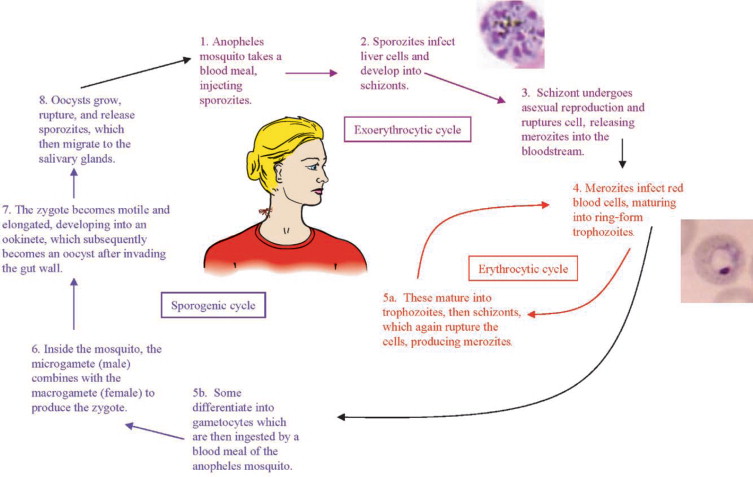

Plasmodium ovale malaria poses a unique challenge due to its capacity for relapse through dormant liver stages known as hypnozoites. While it is not as widespread as P. falciparum or P. vivax, its presence in Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and Papua New Guinea calls for robust prevention measures. We examine effective preventive strategies, including vector control, chemoprophylaxis, and public health interventions, to mitigate the spread and recurrence of Plasmodium ovale malaria.

Understanding the Risk: The Unique Nature of Plasmodium ovale

Before implementing preventive measures, it is essential to understand why P. ovale requires specific attention.

- Dormancy and Relapse: P. ovale can remain in the liver as hypnozoites, reactivating weeks or months after initial infection.

- Low Parasitemia: It often presents with mild symptoms, leading to underdiagnosis and continued transmission.

- Geographical Distribution: Though less common globally, it is endemic to key tropical regions with significant travel exposure.

Personal Protection: First Line of Defense Against Infected Mosquitoes

Avoiding mosquito bites remains the most immediate and effective form of malaria prevention.

Use of Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs)

- Sleeping under long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) significantly reduces exposure to infected Anopheles mosquitoes.

- Nets should be inspected regularly for tears and replaced when necessary.

Mosquito Repellents and Clothing

- DEET (20–50%), Picaridin, or IR3535-based repellents provide excellent topical protection.

- Wear long-sleeved clothing, especially at dusk and dawn when mosquito activity peaks.

- Clothing treated with permethrin enhances repellency and adds an additional layer of protection.

Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS)

- Applying residual insecticides to walls kills mosquitoes resting indoors and reduces transmission rates significantly.

- Community-wide spraying is most effective in high-risk zones with coordinated health authority involvement.

Chemoprophylaxis: Preventing Infection in High-Risk Individuals

Travelers to endemic regions and residents in seasonal transmission zones require pharmaceutical intervention.

Recommended Chemoprophylactic Agents

- Atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline, and mefloquine are standard options for blood-stage suppression.

- These drugs prevent symptomatic malaria but do not eliminate liver-stage hypnozoites of P. ovale.

Terminal Prophylaxis with Primaquine

- To prevent relapse, primaquine is administered after return from endemic areas or following blood-stage prophylaxis.

- A G6PD deficiency screening is mandatory before prescribing primaquine due to the risk of hemolytic anemia.

Tafenoquine as an Alternative

- A single-dose alternative to primaquine, tafenoquine, also requires G6PD testing and is effective against hypnozoites.

- Its long half-life allows for simplified treatment regimens in appropriate candidates.

Vector Control: Breaking the Transmission Cycle

Comprehensive environmental control measures help eliminate the vector population and limit disease spread.

Larval Source Management

- Draining stagnant water, covering water storage containers, and introducing larvivorous fish reduce breeding sites.

- Biological larvicides like Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis (Bti) can be deployed safely in community water bodies.

Community Education and Involvement

- Involving local communities in vector control initiatives ensures long-term success and adherence.

- Programs should include awareness campaigns, mosquito monitoring, and school-based education on prevention.

Early Diagnosis and Treatment: Preventing Further Transmission

Prompt identification and complete treatment are essential to stop the parasite’s life cycle.

Active Case Surveillance

- In endemic areas, active detection of symptomatic and asymptomatic carriers is critical.

- Relapse cases often occur outside transmission seasons, highlighting the need for extended surveillance.

Diagnostic Accuracy

- Microscopy and PCR should be employed for detecting P. ovale, especially when RDTs yield negative or ambiguous results.

- Confirmed infections must be treated with both blood schizonticidal and hypnozoitocidal agents to prevent future relapses.

Travel Advisory Measures: Educating and Preparing Travelers

International travelers play a key role in introducing P. ovale to non-endemic regions if not properly protected.

Pre-Travel Consultation

- Seek medical advice 4–6 weeks before departure to arrange prophylaxis and vaccinations.

- Discuss destination-specific risks and ensure proper health documentation.

Post-Travel Monitoring

- Monitor for malaria symptoms for at least 12 months after return from endemic areas.

- Relapse from P. ovale may occur long after exposure, especially in non-immune individuals.

Integrated Public Health Interventions

Government-led and NGO-supported programs must work collaboratively to implement effective malaria control strategies.

Inclusion in National Malaria Programs

- Many national plans focus primarily on P. falciparum; inclusion of P. ovale in surveillance and treatment guidelines is essential.

- Monitoring mixed infections ensures no species is overlooked during elimination campaigns.

Global Health Partnerships

- Organizations like WHO, CDC, and Roll Back Malaria support the inclusion of non-falciparum species in global elimination targets.

- International funding and technical expertise improve access to diagnostics, medications, and training.

FAQs

Q1: What is the best way to prevent Plasmodium ovale malaria?

The most effective strategy combines personal mosquito protection, chemoprophylaxis with primaquine or tafenoquine, and public health interventions.

Q2: Can malaria vaccines prevent P. ovale infection?

Current vaccines target P. falciparum. There is no approved vaccine for P. ovale at present.

Q3: Why is G6PD testing necessary for relapse prevention?

Drugs like primaquine and tafenoquine can cause severe hemolysis in G6PD-deficient individuals. Testing ensures safe administration.

Q4: How long should travelers monitor for symptoms after visiting endemic regions?

Travelers should watch for symptoms for at least 12 months, as P. ovale relapses may occur long after return.

Q5: Is P. ovale contagious from person to person?

No. Transmission occurs exclusively through the bite of infected Anopheles mosquitoes, not via direct human contact.

Preventing Plasmodium ovale malaria requires a multifaceted approach addressing both immediate mosquito exposure and the long-term risk of relapse. By combining personal protection, chemoprophylaxis, environmental vector control, and coordinated public health efforts, we can significantly reduce the incidence and burden of this relapsing form of malaria. Strategic action in endemic and travel-associated regions is essential to achieving long-term malaria control and eventual eradication.