Plasmodium malariae is one of the five Plasmodium species known to infect humans, responsible for causing quartan malaria. Although less prevalent than P. falciparum and P. vivax, P. malariae presents a persistent threat due to its long-lasting infections, potential to remain undiagnosed for years, and chronic health effects. Comprehensive knowledge of this species is essential for clinicians, researchers, and global health organizations seeking to eliminate malaria.

Overview of Plasmodium malariae: The Quartan Malaria Agent

Plasmodium malariae is a protozoan parasite that causes a milder but more prolonged form of malaria. It is primarily found in sub-Saharan Africa, parts of Southeast Asia, and the Western Pacific.

Biological Characteristics

- Incubation period: Typically 18–40 days post-infection.

- Erythrocytic cycle duration: 72 hours (quartan periodicity), resulting in fever every third day.

- Host specificity: Infects older red blood cells, limiting its parasitemia but enabling long-term persistence.

- Relapse potential: Unlike P. vivax and P. ovale, it does not form hypnozoites but can cause prolonged low-grade infections.

Transmission Dynamics of Plasmodium malariae

Vector and Reservoir

- Vector: Female Anopheles mosquitoes, particularly those species active in forested or rural regions.

- Transmission: Occurs when sporozoites are injected during a blood meal and travel to the liver to initiate infection.

- Reservoir: Humans are the sole significant reservoir; however, some simian species have been identified as potential hosts.

Epidemiology

- P. malariae is less common but has a wider geographical spread, often co-existing with P. falciparum.

- Chronic carriers may remain asymptomatic for years, contributing to silent transmission.

Clinical Presentation of Malariae Malaria

Symptoms of Plasmodium malariae Infection

- Classic febrile paroxysms occurring every 72 hours.

- Chills, followed by fever and then intense sweating.

- Mild to moderate anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, and fatigue.

Complications

- Though generally less severe than falciparum malaria, complications can include:

- Nephrotic syndrome (especially in children)

- Chronic renal insufficiency

- Splenic rupture in rare cases

- Longstanding infections may result in chronic immune stimulation.

Diagnostic Methods for Plasmodium malariae

Accurate diagnosis is critical for effective treatment and control. However, P. malariae can be easily overlooked due to its low parasitemia and nonspecific symptoms.

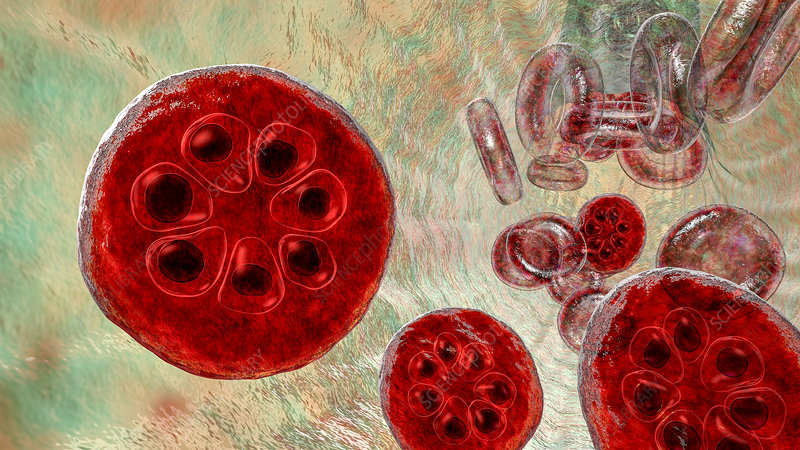

Microscopy

- Thick and thin blood smears remain the gold standard.

- Key features:

- Band-form trophozoites

- Rosette schizonts with 6–12 merozoites

- Characteristic quartan periodicity

Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs)

- Less sensitive for P. malariae due to low antigen levels.

- Many RDTs prioritize detection of P. falciparum or pan-malarial antigens.

Molecular Techniques

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) offers high sensitivity and specificity.

- Useful in mixed infections or asymptomatic carriers.

Treatment Guidelines for Plasmodium malariae Infection

P. malariae is typically responsive to several antimalarial drugs. Prompt and complete treatment is necessary to prevent complications and halt transmission.

First-Line Treatment

- Chloroquine remains the treatment of choice due to its efficacy and low resistance rates.

- Dosage: 25 mg/kg over three days in adults and children.

Alternative Therapies

- Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) such as artemether-lumefantrine, though primarily designed for P. falciparum, are effective and may be used in mixed infections.

- Primaquine is not needed as P. malariae does not form liver hypnozoites.

Preventive Measures Against Plasmodium malariae

Prevention strategies for P. malariae mirror those used for other human malaria parasites, focusing on vector control and personal protection.

Vector Control Interventions

- Insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs) and long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs)

- Indoor residual spraying (IRS)

- Environmental management to reduce mosquito breeding sites

Personal Protective Measures

- Use of repellents containing DEET or picaridin

- Wearing long-sleeved clothing

- Installation of screening in homes

Surveillance and Case Detection

- Active and passive case detection, especially in co-endemic regions, is crucial for early diagnosis and prompt treatment.

- Mass screening in endemic areas may uncover asymptomatic carriers sustaining transmission cycles.

Global Burden and Control Challenges

Though often overshadowed by P. falciparum, P. malariae poses unique control challenges:

Hidden Transmission

- Asymptomatic carriers can harbor infections for years, escaping routine surveillance.

- Chronic low-level infections facilitate ongoing transmission despite intervention efforts.

Diagnostic Oversights

- Microscopy expertise is essential, as P. malariae can be confused with P. vivax or missed in co-infections.

- RDTs may underreport malariae cases due to low antigen expression.

Integration into Malaria Control Programs

- National control programs should specifically include P. malariae in surveillance and elimination strategies.

- Mixed infection management and targeted treatment policies can help address gaps in care.

FAQs:

Q1: How is Plasmodium malariae different from Plasmodium falciparum?

P. malariae has a 72-hour erythrocytic cycle, causes less severe disease, and can persist for years, unlike the more acute and severe P. falciparum.

Q2: Can Plasmodium malariae cause relapses like P. vivax?

No. It does not form hypnozoites. However, it can persist as a low-level blood infection for decades.

Q3: What is the preferred treatment for malariae malaria?

Chloroquine is the drug of choice, though ACTs are also effective, especially in mixed infections.

Q4: Is P. malariae fatal?

Rarely. It is typically mild but can lead to complications such as nephrotic syndrome or chronic anemia if untreated.

Q5: Can someone have malariae malaria without symptoms?

Yes. Asymptomatic infections are common and can last for years, contributing to hidden transmission.

Plasmodium malariae, though often overlooked, plays a silent but persistent role in malaria-endemic regions. Its long-term carriage, diagnostic challenges, and chronic complications make it a priority in the fight against malaria. Through enhanced surveillance, improved diagnostics, targeted treatment, and vector control, we can mitigate its impact and move closer to a malaria-free future.