Plasmodium falciparum malaria continues to pose a serious threat to global public health, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and other tropical regions. Preventing this deadly parasitic disease requires an integrated, multifaceted approach that targets the parasite, its mosquito vector, and the conditions that support its transmission. The following prevention methods reflect current best practices, grounded in scientific research and global health guidelines.

Integrated Vector Management: The Foundation of Malaria Prevention

Vector control remains the cornerstone of Plasmodium falciparum malaria prevention. By disrupting the life cycle of the Anopheles mosquito, the primary vector, we can significantly reduce transmission rates.

Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs)

- Long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) are recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for use in endemic areas.

- They provide a physical barrier and chemical protection, especially effective when used consistently during sleep.

- LLIN distribution campaigns are pivotal in high-burden regions, with over 2 billion nets distributed globally since 2004.

Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS)

- Involves spraying walls and surfaces with residual insecticides effective against mosquitoes resting indoors.

- Effective for 3–6 months, depending on the chemical used.

- Best deployed in seasonal transmission zones or areas with insecticide-sensitive mosquito populations.

Environmental Management and Larval Control

- Eliminating standing water sources to reduce mosquito breeding habitats.

- Introduction of larvicides in water bodies and biological controls such as larvivorous fish.

- Urban planning and sanitation improvements help reduce vector density long-term.

Chemoprophylaxis and Preventive Treatment

Prophylactic use of antimalarial drugs offers targeted protection to high-risk populations and travelers entering endemic zones.

Malaria Chemoprophylaxis for Travelers

Recommended for individuals from non-endemic regions traveling to areas with P. falciparum transmission. Common regimens include:

- Atovaquone-proguanil

- Doxycycline

- Mefloquine

These drugs must be started before travel, continued during exposure, and for a prescribed period after departure to ensure full protection.

Intermittent Preventive Treatment (IPT)

IPT in Infants (IPTi)

- Administered with routine immunizations in high transmission areas.

- Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) is used to reduce infant mortality and morbidity.

IPT in Pregnancy (IPTp)

- Pregnant women receive intermittent doses of SP during antenatal visits after the first trimester.

- Prevents maternal anemia, placental malaria, and low birth weight in newborns.

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (SMC)

- For children under five in regions with highly seasonal transmission, especially in the Sahel sub-region.

- Monthly courses of SP + amodiaquine during the rainy season significantly reduce incidence.

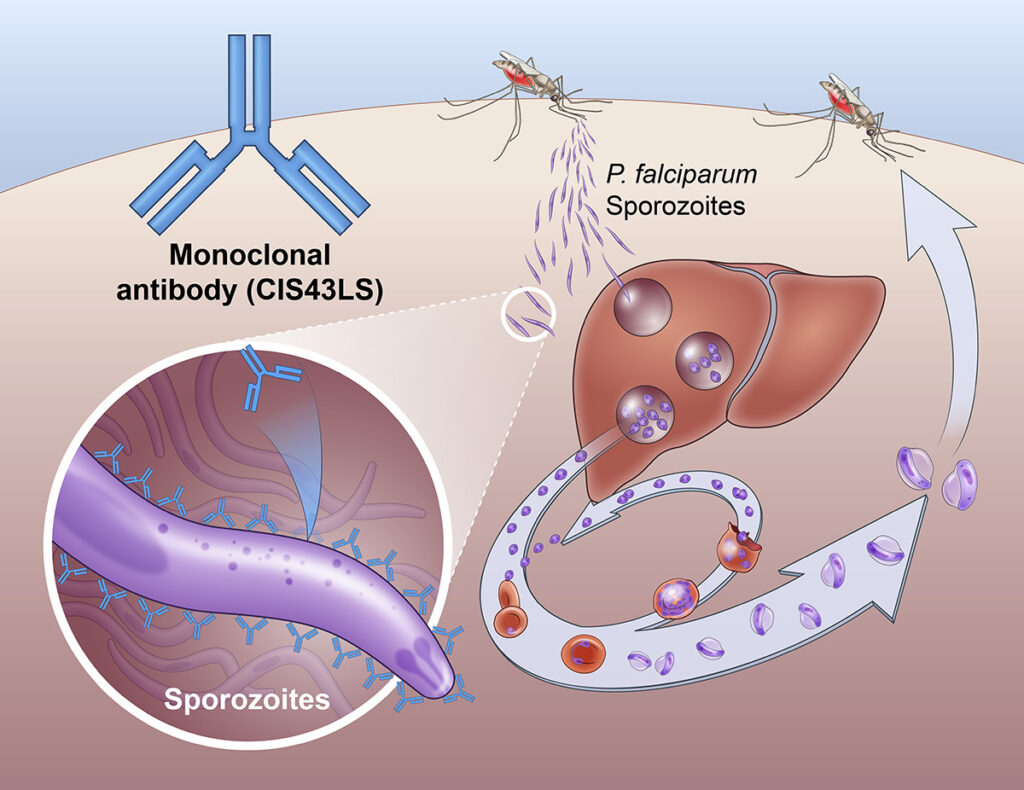

Vaccine Development and Immunization Programs

Vaccination has become a promising frontier in malaria prevention, particularly for Plasmodium falciparum.

RTS,S/AS01 (Mosquirix)

- The first WHO-recommended malaria vaccine, designed specifically for P. falciparum.

- Provides partial protection against clinical malaria in young children.

- Requires four doses, starting at 5 months of age.

R21/Matrix-M

- A newer candidate with higher efficacy levels in trials.

- Approved in several countries and expected to play a key role in elimination efforts.

These vaccines, when combined with vector control and IPT, form a comprehensive shield against infection in vulnerable populations.

Personal Protection Measures

Individual behavior plays a vital role in preventing mosquito bites and minimizing infection risk.

Protective Clothing and Repellents

- Wearing long-sleeved garments during peak mosquito activity (dusk to dawn).

- Applying DEET-based or picaridin-based repellents on exposed skin.

Screening and Mosquito-Proofing

- Use of window screens, door screens, and mosquito-proof housing.

- Sleeping in air-conditioned environments further reduces risk.

Monitoring, Surveillance, and Public Health Infrastructure

An effective prevention strategy relies on robust data collection, community engagement, and responsive health systems.

Malaria Surveillance Systems

- Real-time tracking of case numbers, geographic trends, and drug resistance.

- Digital tools and mobile reporting enhance early detection and response.

Community Education and Mobilization

- Education campaigns focused on net usage, symptom recognition, and early treatment seeking.

- Collaboration with local leaders enhances trust and participation in control programs.

Global Partnerships and Funding

- The Global Fund, PMI (President’s Malaria Initiative), and WHO coordinate funding and implementation support.

- Investment in research, infrastructure, and innovative tools remains crucial to sustaining progress.

Addressing Insecticide and Drug Resistance

The emergence of insecticide-resistant Anopheles mosquitoes and multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum strains threatens current prevention efforts.

Resistance Management Tactics:

- Rotational use of insecticides with different modes of action.

- Development of next-generation nets incorporating dual insecticides (e.g., pyrethroid + piperonyl butoxide).

- Investment in new antimalarial compounds to replace drugs losing efficacy.

Long-Term Goals: Elimination and Eradication

Sustained malaria prevention programs aim to transition from control to elimination in specific regions, with ultimate eradication as the global goal.

Key Milestones:

- Pre-elimination phase: Low transmission maintained through surveillance and reactive case detection.

- Elimination: No indigenous cases in a defined area for three years.

- Eradication: Global interruption of malaria transmission.

Continued political commitment, scientific innovation, and international collaboration will be essential to achieve these goals.

FAQs

Q1: What is the most effective way to prevent falciparum malaria?

Combining insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor spraying, antimalarial prophylaxis, and vaccination provides the best protection.

Q2: Can malaria vaccines completely prevent the disease?

Current vaccines offer partial protection but significantly reduce severe illness and hospitalization rates when used alongside other measures.

Q3: Are insecticide-treated nets still effective with rising mosquito resistance?

Yes, especially newer LLINs treated with multiple insecticides or synergists designed to overcome resistance.

Q4: Is chemoprophylaxis safe for long-term travelers?

Yes, when prescribed appropriately. Regular monitoring for side effects is advised for prolonged use.

Q5: Why is falciparum malaria more challenging to prevent than other forms?

Due to its rapid life cycle, higher transmission potential, and growing resistance to both insecticides and antimalarial drugs.

Preventing Plasmodium falciparum malaria requires a strategic blend of vector control, chemoprophylaxis, vaccination, and community engagement, supported by continuous surveillance and global cooperation. Through consistent application of proven methods and adoption of emerging technologies, we can advance toward a future free from falciparum malaria.