Plasmodium falciparum is the most virulent species of the malaria-causing parasites that infect humans, responsible for the majority of malaria-related deaths worldwide. It thrives in tropical and subtropical regions, with sub-Saharan Africa bearing the highest burden. The disease it causes, falciparum malaria, is a life-threatening condition requiring prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Understanding Plasmodium falciparum: The Deadliest Malaria Parasite

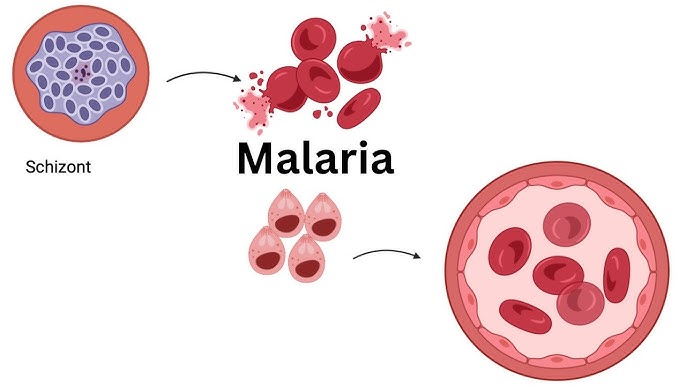

Plasmodium falciparum is a protozoan parasite transmitted through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. Upon entering the human bloodstream, the parasite invades liver cells, multiplies, and then infects red blood cells, initiating a cycle that leads to clinical disease.

It differs from other Plasmodium species by its ability to cause severe and cerebral malaria, owing to its capacity for cytoadherence—where infected erythrocytes adhere to vascular endothelium, blocking microcirculation and triggering inflammation.

Life Cycle of Plasmodium falciparum

The life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum involves both a human host and a mosquito vector, with distinct stages in each.

Lifecycle Overview:

This cycle typically spans 48 hours in the human host and is responsible for the characteristic paroxysmal fevers.

Transmission and Epidemiology

Transmission of Plasmodium falciparum occurs primarily in:

- Tropical Africa

- Southeast Asia

- South America

- Western Pacific regions

Factors Influencing Transmission:

- Climate (warm, humid environments favor vector survival)

- Mosquito density

- Population immunity

- Human movement and travel

In areas of high endemicity, partial immunity may develop over time, especially in adults.

Clinical Manifestations and Symptoms

The symptoms of Plasmodium falciparum malaria typically begin 10–14 days after infection. Initial manifestations resemble a flu-like illness, but rapid progression can lead to severe complications.

Common Symptoms:

- High-grade fever with chills

- Headache and myalgia

- Vomiting and nausea

- Profuse sweating

- Fatigue and malaise

Severe Malaria Symptoms:

- Cerebral malaria: seizures, confusion, coma

- Severe anemia: due to destruction of red blood cells

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Renal failure

- Hypoglycemia

- Metabolic acidosis

Without treatment, cerebral malaria can be fatal within 24–48 hours of onset.

Diagnosis of Falciparum Malaria

Accurate and timely diagnosis is critical to reduce mortality. Both microscopic and molecular methods are employed.

Diagnostic Techniques:

- Microscopy (Gold Standard):

- Giemsa-stained thick and thin blood smears

- Identifies parasite species and density

- Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs):

- Detect specific Plasmodium antigens

- Useful in remote or resource-limited settings

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR):

- High sensitivity and specificity

- Differentiates Plasmodium species

- Serologic Tests:

- Detect antibodies, useful in epidemiologic surveys

Treatment of Plasmodium falciparum Malaria

Treatment depends on disease severity, drug resistance patterns, and geographic location.

Uncomplicated Falciparum Malaria:

First-line treatment (as per WHO):

- Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies (ACTs):

- Artemether-lumefantrine

- Artesunate-amodiaquine

- Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine

ACTs are preferred due to:

- Rapid parasite clearance

- Reduced resistance development

Severe or Complicated Malaria:

- Intravenous Artesunate: Preferred for initial therapy

- Followed by oral ACTs once patient can tolerate oral intake

Supportive treatments:

- Antipyretics (e.g., paracetamol)

- Blood transfusions for anemia

- Intravenous fluids and electrolyte management

- Anticonvulsants if seizures occur

Drug Resistance and Control Strategies

Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance, particularly to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, has emerged in several regions, complicating treatment protocols.

Resistance Monitoring:

- Molecular markers (e.g., pfcrt, pfmdr1 mutations)

- Surveillance programs in endemic areas

Prevention Strategies:

- Insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs)

- Indoor residual spraying (IRS)

- Intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) in pregnancy and infants

- Travel prophylaxis for non-immune individuals

Vaccine research is ongoing, with RTS,S/AS01 showing partial protection.

Complications and Long-Term Effects

Without early intervention, Plasmodium falciparum malaria can lead to:

- Neurocognitive impairment (in survivors of cerebral malaria)

- Chronic anemia

- Organ damage (kidneys, lungs, brain)

- Increased susceptibility to other infections

In pregnancy, the parasite can cross the placenta, causing placental malaria, leading to intrauterine growth restriction and low birth weight.

Global Burden and Public Health Impact

Plasmodium falciparum remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, especially among:

- Children under five

- Pregnant women

- Immunocompromised individuals

WHO 2023 Estimates:

- ~247 million malaria cases globally

- ~619,000 deaths, 95% in Africa

- Falciparum species responsible for 99.7% of African malaria cases

FAQs

Q1: What makes Plasmodium falciparum more dangerous than other species?

It causes severe disease due to its ability to adhere to blood vessel walls, blocking microcirculation and damaging organs.

Q2: Can falciparum malaria be cured?

Yes, with timely diagnosis and appropriate antimalarial therapy, especially ACTs or intravenous artesunate for severe cases.

Q3: How can falciparum malaria be prevented?

Using insecticide-treated nets, indoor spraying, prophylactic medication for travelers, and vector control strategies.

Q4: Is there a vaccine for Plasmodium falciparum?

RTS,S/AS01 is the first approved malaria vaccine offering partial protection, with newer vaccines under development.

Q5: Can you get malaria more than once?

Yes. Immunity develops slowly, and reinfection is common in endemic regions without sustained preventive measures.

Plasmodium falciparum malaria remains a global health challenge, particularly in resource-limited settings. Its aggressive pathophysiology, rapid progression, and drug resistance necessitate robust surveillance, effective therapies, and integrated prevention programs. Global efforts in vaccine development and vector control offer hope for sustained reduction in disease burden. Comprehensive public health strategies, grounded in scientific understanding and community engagement, are essential to ultimately eradicate falciparum malaria.