Phenylketonuria (PKU) is a rare but serious autosomal recessive metabolic disorder that affects the body’s ability to metabolize the amino acid phenylalanine. Without prompt diagnosis and dietary intervention, PKU can result in irreversible intellectual disability and neurological impairment. This article presents a detailed, evidence-based overview of PKU, its pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, management, and preventive strategies.

Understanding the Genetic Basis of Phenylketonuria

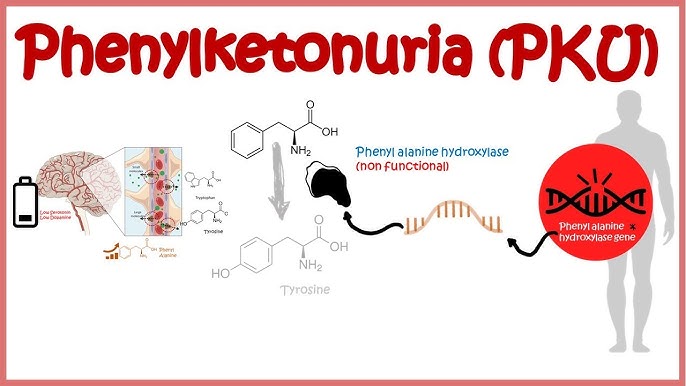

Phenylketonuria is caused by mutations in the PAH gene located on chromosome 12q23.2. This gene encodes the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase, which is responsible for converting phenylalanine into tyrosine — a precursor for neurotransmitters like dopamine and norepinephrine.

In PKU, the deficiency or malfunction of this enzyme leads to the accumulation of phenylalanine in the blood and brain, causing toxic effects on neuronal development.

Types of Phenylketonuria and Phenylalanine Levels

PKU manifests in several forms based on the degree of enzymatic activity:

| Type | Blood Phenylalanine (μmol/L) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Classic PKU | >1200 | Severe enzyme deficiency |

| Moderate PKU | 600–1200 | Partial enzyme function |

| Mild PKU | 360–600 | Mild enzyme deficiency |

| Non-PKU Hyperphenylalaninemia | 120–360 | Usually asymptomatic |

Clinical Manifestations of Phenylketonuria

Newborns with PKU appear normal at birth due to maternal detoxification of phenylalanine. However, if untreated, symptoms typically appear within the first few months of life:

- Developmental delay

- Microcephaly

- Seizures

- Musty or mousy body odor due to phenylacetate accumulation

- Eczema-like skin rashes

- Hypopigmentation (light skin, hair, and eyes)

- Behavioral disturbances such as hyperactivity and aggression

Diagnostic Approach to Phenylketonuria

Newborn Screening

Universal newborn screening is the cornerstone of PKU detection. The Guthrie bacterial inhibition assay was historically used, but modern screening utilizes tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), offering higher specificity and sensitivity.

Screening is typically performed 24–72 hours after birth and measures elevated phenylalanine levels in dried blood spots.

Confirmatory Testing

If elevated levels are detected:

- Repeat quantitative plasma amino acid analysis

- Molecular genetic testing to identify PAH mutations

- BH4 loading test to distinguish PAH deficiency from tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) deficiencies

Pathophysiology and Neurological Impact

Phenylalanine competes with other large neutral amino acids (LNAAs) for transport across the blood-brain barrier. High phenylalanine saturates the transporter, reducing brain levels of tyrosine and tryptophan, thus impairing neurotransmitter synthesis.

This disruption in serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine production leads to severe cognitive and behavioral deficits if not managed early.

Management and Long-Term Treatment of PKU

Lifelong Dietary Management

The cornerstone of PKU treatment is strict phenylalanine restriction:

- Low-protein diet: Avoid meats, dairy, nuts, soy, and aspartame-containing products

- Special PKU formulas: Provide essential amino acids minus phenylalanine

- Frequent blood monitoring: Maintain phenylalanine levels between 120–360 µmol/L in children and <600 µmol/L in adults

Pharmacological Therapy

- Sapropterin dihydrochloride (BH4 analog): Enhances residual PAH activity in responsive patients

- Pegvaliase: An enzyme substitution therapy approved for adults with uncontrolled phenylalanine levels

Emerging Therapies

- Gene therapy: In preclinical and clinical trial phases

- mRNA therapy: Targeting restoration of PAH expression

- Enzyme encapsulation and oral delivery systems are under exploration

Maternal PKU and Pregnancy Considerations

Women with PKU must maintain tight phenylalanine control before and during pregnancy to prevent maternal PKU syndrome, which includes:

- Microcephaly

- Congenital heart defects

- Growth retardation

- Intellectual disability in the fetus

Preconception counseling and intensive dietary management are critical to ensure fetal health.

Prognosis and Quality of Life

With early diagnosis and lifelong dietary adherence, individuals with PKU can lead healthy, productive lives. However, lapses in dietary control during adolescence or adulthood can lead to:

- Executive function deficits

- Mood disorders

- Decreased quality of life

Thus, lifelong follow-up with metabolic specialists, dietitians, and psychologists is essential.

Public Health Strategies and Screening Policies

- Mandatory newborn screening in most developed countries

- Education and awareness campaigns for parents and healthcare providers

- Subsidization of medical foods and metabolic formulas by governments and insurance systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is PKU curable?

PKU is not curable but is effectively manageable through diet and medical therapy.

Can adults develop PKU?

PKU is a congenital condition, but late diagnosis may occur in countries lacking newborn screening.

Is aspartame safe for people with PKU?

No. Aspartame contains phenylalanine and must be strictly avoided.

Do individuals with PKU need dietary treatment for life?

Yes. Lifelong dietary therapy is recommended to maintain optimal cognitive functioning.

Are siblings at risk?

Yes. PKU is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner; genetic counseling is recommended for families.

Phenylketonuria, while rare, poses significant neurodevelopmental risks if undiagnosed or improperly managed. However, with universal newborn screening, prompt dietary therapy, and novel pharmacological advancements, individuals with PKU can achieve normal development and a high quality of life. Continued investment in public health strategies, patient education, and research is imperative to enhance outcomes for all those affected by this genetic metabolic disorder.