Perioperative hypertension refers to elevated blood pressure occurring in the preoperative, intraoperative, or postoperative phases of surgery. It is a critical clinical entity associated with heightened cardiovascular risk, cerebrovascular events, and surgical complications. Optimal management is essential to minimize morbidity and mortality, particularly in patients with known hypertension or cardiovascular comorbidities.

Etiology and Risk Factors

Preoperative Hypertension

Patients presenting with sustained hypertension prior to surgery are at greater risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications. Contributing factors include:

- Poorly controlled essential hypertension

- Anxiety and sympathetic stimulation (white coat effect)

- Non-compliance with antihypertensive therapy

- Secondary hypertension (renal, endocrine, medication-induced)

Intraoperative Hypertension

Intraoperative elevations in blood pressure may result from:

- Insufficient anesthetic depth

- Surgical stimulation

- Laryngoscopy and intubation

- Use of vasopressors or inotropes

- Emergence from anesthesia

Postoperative Hypertension

Postoperative spikes in blood pressure are commonly associated with:

- Pain and agitation

- Hypoxia and hypercapnia

- Urinary retention

- Rebound hypertension due to abrupt discontinuation of medications

- Volume overload or fluid shifts

Hemodynamic Consequences and Complications

Sustained or severe perioperative hypertension can precipitate life-threatening complications:

- Myocardial ischemia and infarction

- Cerebrovascular accidents

- Acute kidney injury

- Excessive surgical bleeding

- Aneurysm rupture in vascular procedures

- Poor wound healing and increased hospital stay

The risk escalates in patients with target organ damage or pre-existing hypertensive heart disease.

Diagnostic Considerations

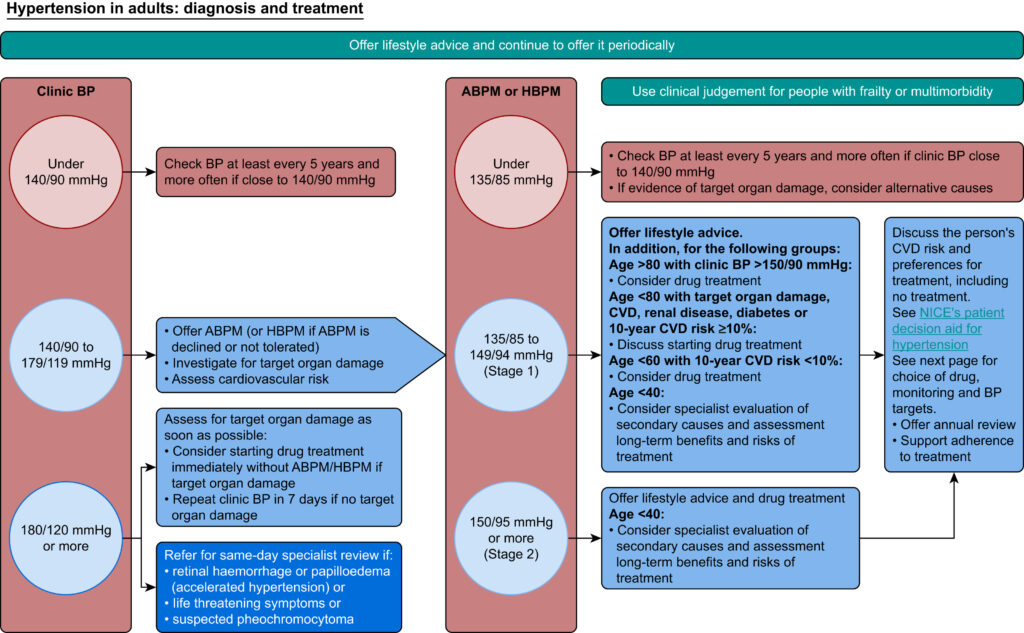

Prior to elective procedures, a thorough pre-anesthetic evaluation is essential to identify hypertensive patients and stratify cardiovascular risk.

Preoperative Assessment

- BP monitoring across multiple readings

- Evaluation for end-organ damage (ECG, echocardiography, renal profile)

- Review of antihypertensive regimen

- Assessment of medication adherence and side effects

- Identification of secondary causes in resistant hypertension

Patients with BP >180/110 mmHg generally require postponement of elective surgery until optimal control is achieved.

Perioperative Management Strategies

Preoperative Optimization

- Continue antihypertensive medications unless contraindicated

- Withhold angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) on day of surgery due to risk of hypotension

- Beta-blockers should be continued if already prescribed

- Consider anxiolytics to attenuate sympathetic response

Intraoperative Management

- Continuous arterial BP monitoring in high-risk cases

- Titrate anesthetic agents to adequate depth

- Use of short-acting intravenous agents such as:

- Esmolol for β-blockade

- Labetalol for mixed α/β-blockade

- Nitroglycerin or nitroprusside for vasodilation

- Clevidipine or nicardipine as calcium channel blockers

- Avoid agents with sympathetic stimulation (e.g., ketamine)

Postoperative Control

- Resume oral antihypertensives as early as feasible

- Use IV agents for severe elevations

- Monitor fluid status and oxygenation

- Manage pain adequately with multimodal analgesia

- Avoid abrupt cessation of centrally acting agents (e.g., clonidine)

Medications Commonly Used in Perioperative Hypertension

| Drug | Class | Onset | Duration | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esmolol | Beta-blocker | 1–2 minutes | 10–20 min | Ideal for intraoperative use |

| Labetalol | Mixed α/β-blocker | 5–10 minutes | 2–6 hours | Useful in both intra- and postoperative phases |

| Nicardipine | Calcium channel blocker | 5–15 minutes | 15–30 min | Preferred in hypertensive emergencies |

| Clevidipine | Dihydropyridine CCB | 2–4 minutes | 5–15 min | Short-acting, easy titration |

| Nitroglycerin | Vasodilator (venous) | 2–5 minutes | 10–20 min | Avoid in volume-depleted patients |

| Nitroprusside | Vasodilator (arterial/venous) | <1 minute | 1–2 min | Requires ICU monitoring; risk of cyanide toxicity |

Special Considerations in High-Risk Populations

Elderly Patients

- Prone to orthostatic hypotension and impaired baroreceptor reflex

- Require gentle titration of antihypertensives

Renal Dysfunction

- Altered drug metabolism and excretion

- Avoid nephrotoxic agents and volume overload

Cardiac Disease

- High risk of ischemia during BP fluctuations

- Continuous ECG and hemodynamic monitoring essential

Surgical Case Postponement Criteria

Elective surgery should be deferred in the presence of:

- SBP >180 mmHg or DBP >110 mmHg

- Active end-organ damage

- Ongoing hypertensive crisis

- Inadequate preoperative evaluation

Stabilization under outpatient or inpatient settings is warranted before proceeding.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. What is the threshold for perioperative hypertension?

A sustained SBP >160 mmHg or DBP >100 mmHg in the surgical setting is generally considered significant.

Q2. Should ACE inhibitors be stopped before surgery?

Yes. Stopping ACE inhibitors 24 hours prior may reduce intraoperative hypotension.

Q3. Which IV drugs are preferred intraoperatively for hypertension?

Short-acting agents such as esmolol, labetalol, nicardipine, and clevidipine are preferred.

Q4. Is general anesthesia safe in uncontrolled hypertensives?

Not until BP is stabilized. Uncontrolled hypertension increases perioperative cardiovascular risk.

Q5. What is white coat hypertension and does it matter before surgery?

White coat hypertension is elevated BP in clinical settings due to anxiety. It must be distinguished from sustained hypertension during evaluation.

Perioperative hypertension represents a major anesthetic and surgical challenge with the potential to precipitate serious adverse events if unmanaged. A multidisciplinary approach, encompassing detailed risk assessment, vigilant intraoperative monitoring, and timely pharmacological intervention, is imperative. Recognizing vulnerable patient populations, understanding the hemodynamic implications, and employing evidence-based therapeutic strategies can lead to safer surgical outcomes and improved patient care.