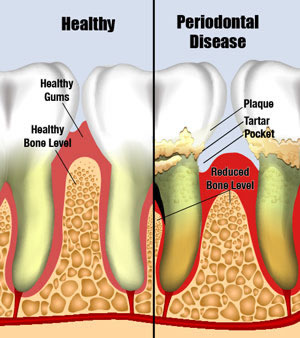

Periodontal infection refers to the inflammatory condition affecting the supporting structures of the teeth, including the gums, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. This infection progresses from gingivitis to periodontitis when left untreated, often resulting in tooth mobility, bone loss, and even tooth loss in advanced stages.

Etiology of Periodontal Infection

Bacterial Pathogenesis

The primary cause of periodontal infection is the accumulation of dental plaque, a biofilm harboring pathogenic bacteria such as:

- Porphyromonas gingivalis

- Tannerella forsythia

- Treponema denticola

These organisms release toxins and enzymes that trigger a destructive immune-inflammatory response.

Risk Factors

- Poor oral hygiene

- Smoking and tobacco use

- Systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus)

- Genetic predisposition

- Hormonal changes (pregnancy, menopause)

- Stress and immunosuppression

- Malocclusion and defective restorations

Progression from Gingivitis to Periodontitis

Periodontal disease follows a clearly defined pathological cascade from reversible inflammation to irreversible tissue damage.

- Gingivitis: Inflammation limited to the gingiva with no attachment loss

- Early Periodontitis: Slight attachment and bone loss

- Moderate Periodontitis: Increased probing depth and bone loss

- Severe Periodontitis: Deep pockets, tooth mobility, and potential tooth loss

Clinical Features and Symptoms

Primary Symptoms

- Bleeding gums during brushing or spontaneously

- Swollen, red, or tender gums

- Halitosis (chronic bad breath)

- Receding gums

- Tooth mobility

- Pus discharge from the gum line

- Change in bite due to shifting teeth

Diagnostic Indicators

- Probing Depth: >3 mm suggests periodontal pocketing

- Clinical Attachment Loss (CAL)

- Radiographic bone loss

- Bleeding on probing (BOP)

Microbiological and Immunological Aspects

The pathogenesis of periodontal infection involves complex interactions between oral microbiota and the host immune system. The innate immune response initially attempts to neutralize pathogens. However, chronic activation leads to:

- Release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α)

- Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) degrading connective tissue

- Osteoclast activation causing bone resorption

Diagnostic Procedures

Clinical Examination

- Periodontal charting of probing depths

- Gingival recession and mobility assessment

Radiographic Imaging

- Periapical and bitewing radiographs to assess bone levels

- Cone-beam CT for complex cases

Microbial Testing

- DNA probe analysis for high-risk bacteria

- Salivary diagnostics for inflammatory markers

Classification of Periodontal Diseases

As per the American Academy of Periodontology and European Federation of Periodontology (2017):

- Necrotizing Periodontal Diseases

- Periodontitis (staged and graded)

- Periodontitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Diseases

Staging (I to IV)

- Based on severity, complexity, and extent of tissue loss

Grading (A to C)

- Based on progression rate and risk factors

Treatment and Management Strategies

Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy

- Scaling and Root Planing (SRP): Mechanical removal of plaque and calculus from root surfaces

- Antimicrobial Therapy:

- Topical: Chlorhexidine, doxycycline gel

- Systemic: Metronidazole, amoxicillin (for aggressive cases)

- Host Modulation Therapy: Sub-antimicrobial dose doxycycline (SDD)

Surgical Interventions

- Flap Surgery: For deep pockets and osseous defects

- Bone Grafting and Guided Tissue Regeneration (GTR)

- Laser Therapy: Minimally invasive pocket decontamination

Maintenance Phase

- 3-month periodontal maintenance schedule

- Regular oral hygiene reinforcement and risk assessment

Periodontal Systemic Interactions

Periodontal Disease and Systemic Health

Growing evidence links periodontal infection to various systemic conditions:

- Diabetes Mellitus: Bidirectional relationship; periodontal therapy improves glycemic control

- Cardiovascular Disease: Inflammation may contribute to atherosclerosis

- Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: Increased risk of preterm birth and low birth weight

- Respiratory Infections: Aspiration of periodontal pathogens

Prevention and Oral Hygiene Strategies

Effective Preventive Measures

- Twice-daily brushing with fluoride toothpaste

- Daily interdental cleaning (floss or interdental brushes)

- Professional dental cleanings every 6 months

- Smoking cessation

- Blood glucose control in diabetic patients

- Periodontal risk assessments during routine dental visits

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1. Can periodontal infection be cured?

While early stages like gingivitis are reversible, periodontitis can only be managed, not cured. Long-term control requires continuous care.

Q2. What is the difference between gingivitis and periodontitis?

Gingivitis is reversible gum inflammation without bone loss. Periodontitis involves attachment and bone destruction, often irreversible.

Q3. Are antibiotics always required for treatment?

No. Antibiotics are adjuncts for specific cases, not substitutes for mechanical debridement and proper oral hygiene.

Q4. Is periodontal disease hereditary?

Genetic predisposition influences susceptibility, but environmental and behavioral factors are more significant.

Q5. How often should one get periodontal maintenance?

Every 3–4 months is typically recommended for individuals with a history of periodontitis.

Periodontal infection is a multifactorial disease with profound implications for both oral and systemic health. Early detection, tailored therapeutic interventions, and rigorous maintenance are vital for effective management. By understanding its etiology, recognizing symptoms early, and adhering to preventive protocols, we can significantly reduce the burden of periodontal disease and enhance quality of life.