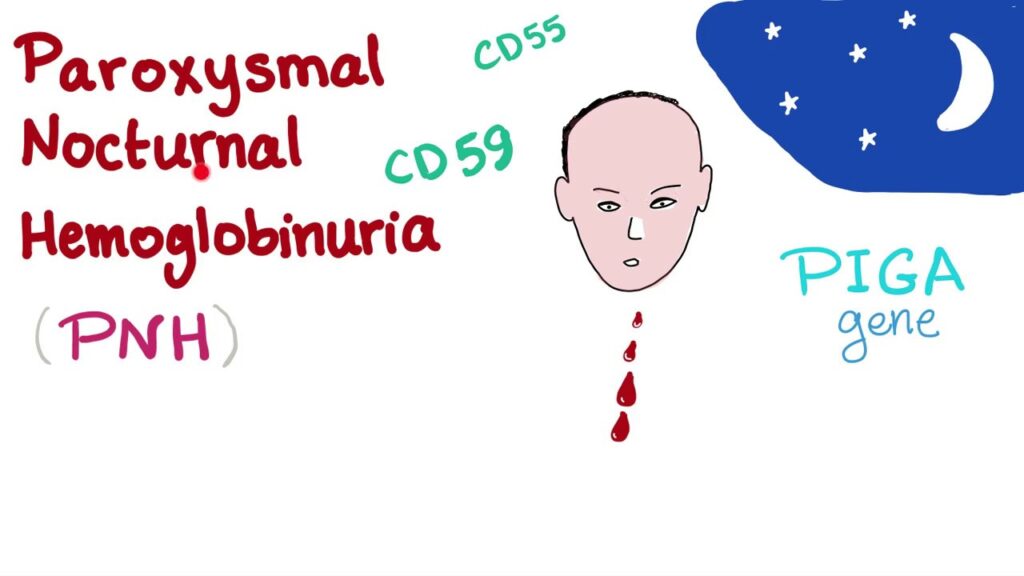

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare, acquired hematologic disorder marked by chronic intravascular hemolysis, bone marrow failure, and a heightened risk of thrombosis. It stems from a somatic mutation in the PIGA gene in hematopoietic stem cells, resulting in defective glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins that regulate complement activity. This deficiency renders red blood cells highly susceptible to complement-mediated lysis.

Pathophysiology of PNH: Complement-Mediated Hemolysis

The hallmark of PNH is the deficiency of two key GPI-anchored complement-regulating proteins: CD55 (decay-accelerating factor) and CD59 (membrane inhibitor of reactive lysis). Without these proteins, red blood cells undergo unregulated complement activation, leading to their destruction within blood vessels.

Clinical Manifestations of PNH

Hemolytic Symptoms

- Hemoglobinuria: Classically dark-colored urine in the morning due to overnight hemolysis

- Fatigue: Resulting from chronic anemia

- Jaundice: Due to increased bilirubin levels from red cell breakdown

- Shortness of Breath and Palpitations: Reflecting decreased oxygen delivery

Thrombotic Events

- Unusual Site Thrombosis: Hepatic (Budd-Chiari syndrome), cerebral, mesenteric, or dermal veins

- Leading Cause of Mortality in PNH: Despite its rarity, thrombosis poses a severe risk

Bone Marrow Failure

- Pancytopenia: Manifesting as anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia

- Association with Aplastic Anemia and Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS)

Diagnostic Approach to Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria

Accurate and early diagnosis of PNH is critical for timely management. Several diagnostic tools are used to identify the hallmark features of the disease.

Flow Cytometry: Gold Standard

Flow cytometry is employed to detect the absence of GPI-anchored proteins on red and white blood cells.

- FLAER (fluorescent aerolysin): Binds directly to GPI anchors, offering superior sensitivity

- CD55/CD59 Expression: Absence confirms the presence of a PNH clone

Complementary Tests

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Reveals anemia, leukopenia, and/or thrombocytopenia

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH): Elevated due to cell lysis

- Haptoglobin: Decreased, reflecting hemoglobin binding

- Bilirubin (Indirect): Often elevated

- Urinalysis: Positive for hemoglobin without red blood cells

- Bone Marrow Biopsy: May show hypoplasia or dysplastic features

Classification of PNH

PNH is classified into three primary clinical subtypes based on the size of the PNH clone and associated symptoms:

| Subtype | Description |

|---|---|

| Classic PNH | Dominant hemolytic symptoms with large PNH clone and minimal marrow failure |

| PNH with Bone Marrow Disorder | Associated with aplastic anemia or MDS; small clone size |

| Subclinical PNH | No hemolysis or thrombosis; PNH clone found incidentally |

PNH and Its Relationship with Aplastic Anemia

Aplastic anemia (AA) and PNH share a close pathogenic relationship. Many patients with AA develop PNH clones, and vice versa. This overlap suggests a shared stem cell injury mechanism, possibly immune-mediated, that favors the expansion of PNH clones resistant to T-cell attack.

Complications of Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria

PNH can lead to severe and life-threatening complications if not managed effectively.

Thrombosis

- Incidence: Affects up to 40% of PNH patients

- Sites: Hepatic, cerebral, portal, and dermal veins

- Mechanism: Platelet activation due to complement attack, hemolysis-induced nitric oxide depletion, and endothelial dysfunction

Renal Impairment

- Mechanism: Chronic hemoglobinuria leading to tubular injury and iron deposition

- Presentation: Hematuria, hypertension, and reduced glomerular filtration rate

Pulmonary Hypertension

- Arises from chronic hemolysis and thromboembolic complications

Treatment Strategies for PNH

Supportive Therapies

- Transfusions: For severe anemia; iron overload must be monitored

- Folate and Iron Supplementation: Supports red blood cell production

- Anticoagulation: For patients with thrombotic episodes or high-risk PNH clones

Complement Inhibition: Targeted Therapies

Eculizumab (Soliris)

- Mechanism: Anti-C5 monoclonal antibody that blocks terminal complement activation

- Benefits: Reduces hemolysis, transfusion need, and thrombosis risk

- Administration: IV infusion every 2 weeks

Ravulizumab (Ultomiris)

- Long-acting C5 Inhibitor: Extended dosing interval (every 8 weeks)

- Similar efficacy to eculizumab with increased patient convenience

Investigational and Emerging Therapies

- Pegcetacoplan: C3 inhibitor approved for PNH with inadequate response to C5 inhibitors

- Danicopan & Iptacopan: Oral Factor D inhibitors under investigation

- Gene Therapy: Promising in early-phase trials

Monitoring and Follow-Up in PNH Management

Continuous monitoring is essential to evaluate therapeutic response and detect disease evolution.

- Clonal Size Assessment: Via flow cytometry at regular intervals

- Thrombosis Surveillance: Especially in high-risk patients

- Renal Function Tests: Routine screening for early damage

- LDH and CBC Monitoring: Indicators of hemolytic activity and marrow function

Prognosis and Life Expectancy

With the advent of complement inhibitors, the survival rate for patients with PNH has significantly improved. Previously, median survival was around 10–15 years post-diagnosis. Today, many patients enjoy a near-normal life expectancy when managed effectively.

Summary Table: Key Facts about PNH

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Somatic PIGA gene mutation |

| Key Proteins Affected | CD55 and CD59 (GPI-anchored complement regulators) |

| Primary Symptoms | Hemoglobinuria, fatigue, thrombosis |

| Gold Standard Test | Flow cytometry with FLAER |

| Mainstay Treatment | Eculizumab, Ravulizumab |

| Common Complications | Thrombosis, renal failure, pulmonary hypertension |

| Prognosis with Treatment | Improved; near-normal life expectancy possible |

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria is a complex but treatable hematologic disorder driven by immune-mediated and genetic mechanisms. Timely diagnosis through advanced flow cytometry and management using targeted complement inhibitors have transformed the therapeutic landscape. Vigilant monitoring, preventive strategies for thrombosis, and novel therapies under development promise continued progress in patient care and outcomes.