Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM) is a systemic granulomatous fungal infection caused primarily by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides lutzii. Endemic to Latin America, particularly Brazil, PCM primarily affects the lungs and mucocutaneous membranes and can disseminate to other organs. The disease represents a significant public health issue in rural agricultural regions, where exposure to soil-dwelling fungi is common.

Etiology and Causative Organisms

PCM is caused by thermally dimorphic fungi of the Paracoccidioides genus. These fungi exist in two forms:

- Mycelial (mold) form in the environment (25°C)

- Yeast form in human tissue (37°C)

Species:

- Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (most common)

- Paracoccidioides lutzii (more prevalent in the Central-West and North regions of Brazil)

Inhalation of airborne conidia is the primary route of infection, after which the fungus transforms into its yeast form in the lungs, initiating infection.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Geographic Distribution

PCM is endemic to Latin America, with Brazil accounting for over 80% of reported cases. Other affected countries include Argentina, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Paraguay.

At-Risk Populations

- Rural workers, particularly men aged 30–60

- Individuals with prolonged soil exposure

- Immunocompromised patients (e.g., HIV, cancer, malnutrition)

- Smokers and alcoholics have an increased risk of chronic disease

Gender Disparity

Estrogen is believed to offer a protective effect, reducing the incidence in women of reproductive age. Thus, the male-to-female ratio can be as high as 15:1 in endemic areas.

Clinical Manifestations

Paracoccidioidomycosis presents in two major clinical forms:

1. Acute/Subacute (Juvenile) Form

- Common in children and adolescents

- Rapid onset and systemic dissemination

- Symptoms:

- Fever

- Weight loss

- Lymphadenopathy

- Hepatosplenomegaly

- Skin lesions

- Bone marrow involvement

2. Chronic (Adult) Form

- Represents ~90% of cases

- Slow progression, often affecting lungs and mucous membranes

- Symptoms:

- Chronic cough

- Hemoptysis

- Hoarseness

- Oral and nasal ulcers

- Weight loss

- Dyspnea

Pathogenesis and Immune Response

Upon inhalation, Paracoccidioides reaches the alveoli, where it transitions to the pathogenic yeast phase. The host immune response plays a pivotal role in disease progression:

- Th1 response: Leads to granuloma formation and containment

- Th2/Th9 response: Associated with disease dissemination

Diagnostic Approach

Timely and accurate diagnosis of PCM is crucial due to its clinical overlap with tuberculosis and other systemic infections.

Laboratory Methods

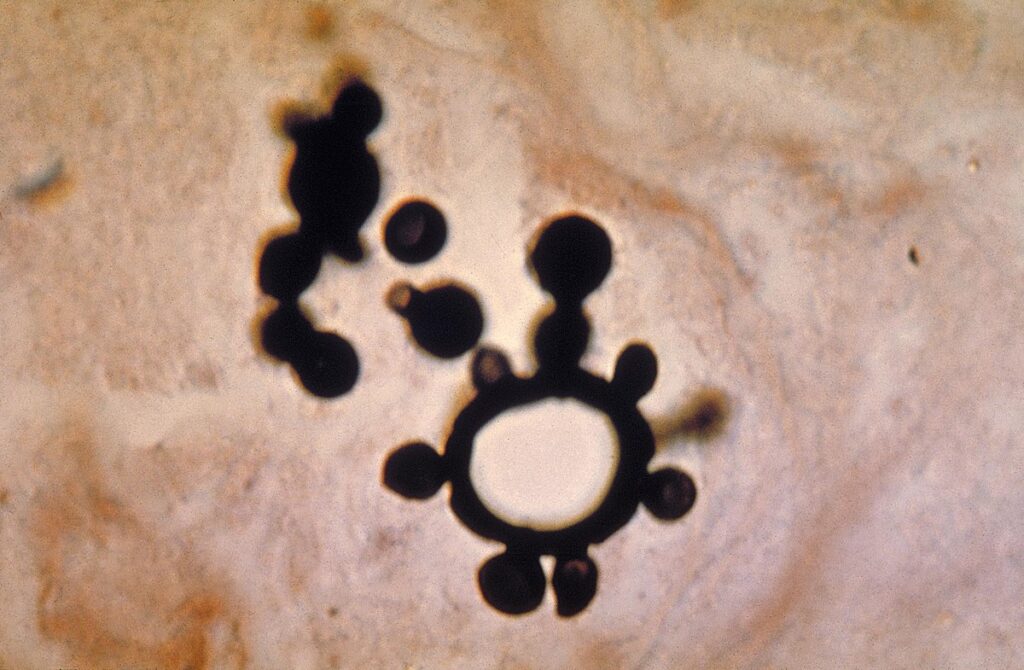

- Direct Microscopy: Identification of characteristic “pilot wheel” or “Mickey Mouse ears” yeast cells in clinical samples (e.g., sputum, lymph node aspirates)

- Culture: Growth on Sabouraud dextrose agar, slow but definitive

- Serology: Detection of antibodies using immunodiffusion, ELISA, or counterimmunoelectrophoresis

- Histopathology: Granulomatous inflammation with multibudding yeast forms

Imaging

- Chest X-ray/CT scan: Bilateral infiltrates, nodules, or cavitations in chronic cases

- Ultrasound/CT of abdomen: For hepatosplenomegaly or lymphadenopathy in juvenile form

Differential Diagnosis

- Tuberculosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Lymphoma

- Leishmaniasis

- Sarcoidosis

Overlap in pulmonary and mucocutaneous symptoms necessitates comprehensive microbiological and histological confirmation.

Treatment and Management

Antifungal Therapy

The choice of antifungal depends on disease severity and patient status.

| Severity | Drug | Dosage | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild to moderate | Itraconazole | 100–200 mg/day | 6–12 months |

| Severe or disseminated | Amphotericin B | 0.5–1 mg/kg/day IV | Until improvement, followed by itraconazole |

| Pediatric/acute forms | Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SMX-TMP) | 800/160 mg BID | 12–24 months |

Monitoring and Follow-up

- Clinical evaluation and imaging at regular intervals

- Serological monitoring for antibody titers

- Long-term follow-up to detect relapses

Prevention and Public Health Strategies

There is no vaccine for PCM. Prevention relies on minimizing risk factors and early detection.

- Avoiding soil disruption in endemic regions

- Use of protective masks by agricultural workers

- Educational campaigns in rural communities

- Routine screening in high-risk populations

Complications and Sequelae

If left untreated or diagnosed late, PCM can lead to serious complications:

- Pulmonary fibrosis

- Laryngeal and oral disfigurement

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Neurological involvement (rare)

- Social stigma due to visible mucocutaneous lesions

Frequently Asked Questions

Is paracoccidioidomycosis contagious?

No. PCM is not transmitted from person to person. Infection occurs through environmental exposure to fungal spores.

How is PCM different from histoplasmosis?

While both are endemic mycoses, they are caused by different fungi and have distinct histopathological features and geographic distribution.

Can PCM relapse after treatment?

Yes. Relapse can occur if treatment is inadequate or interrupted. Long-term follow-up is essential.

What is the prognosis of PCM?

With proper antifungal therapy, the prognosis is favorable. Chronic cases may require extended treatment and supportive care for sequelae.