Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), commonly referred to as brittle bone disease, is a rare, inherited connective tissue disorder characterized by extreme bone fragility, recurrent fractures, and skeletal deformities. It results primarily from mutations in genes responsible for the production of type I collagen, a key structural protein in bone, skin, and other tissues. The condition varies significantly in severity, from mild forms with few fractures to perinatal lethality in the most severe types.

Genetic Basis and Pathophysiology of OI

Role of Collagen in Bone Integrity

Type I collagen provides tensile strength and structural stability to bones. Mutations in the COL1A1 or COL1A2 genes disrupt normal collagen synthesis, leading to either reduced collagen production or abnormal collagen structure. This biochemical defect compromises bone matrix formation, predisposing bones to fracture with minimal trauma.

Inheritance Patterns

- Autosomal Dominant: Most common form; a single copy of the mutated gene can cause the disorder.

- Autosomal Recessive: Less common; both gene copies must be mutated.

- De Novo Mutations: In many cases, no family history is present due to spontaneous mutations.

Classification: Types of Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta is categorized into several types based on clinical severity and genetic cause. The Sillence classification system remains widely used.

Classic Sillence Types

| Type | Severity | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| I | Mild | Blue sclerae, few fractures, normal height |

| II | Perinatal lethal | Severe deformities, underdeveloped lungs, death shortly after birth |

| III | Severe | Progressive bone deformities, very short stature, frequent fractures |

| IV | Moderate | Variable severity, normal sclerae, mild-to-moderate bone fragility |

Additional Types (V–XI)

Later discoveries introduced types V through XI with distinct histological and genetic profiles, including interosseous membrane calcification and hyperplastic callus formation.

Clinical Manifestations and Symptoms

OI affects multiple organ systems, with hallmark signs involving the skeletal system.

Skeletal Symptoms

- Frequent fractures with minimal trauma

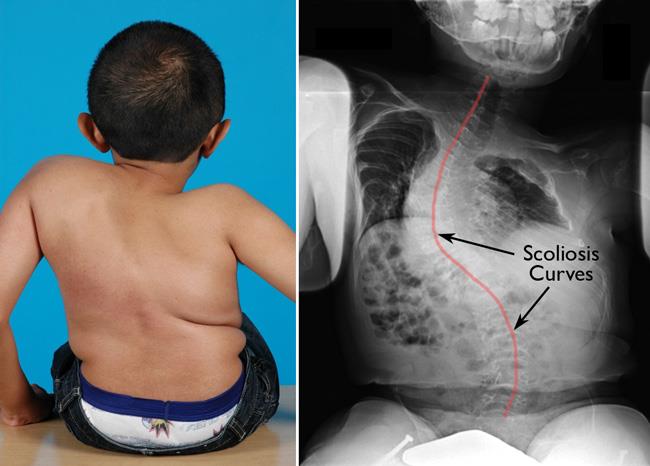

- Bone deformities (bowed limbs, scoliosis)

- Short stature

- Joint hypermobility

- Skull abnormalities (platybasia)

Extraskeletal Features

- Blue Sclerae: Thinning of the sclera allows visualization of underlying choroidal veins.

- Dentinogenesis Imperfecta: Opalescent teeth prone to wear and breakage.

- Hearing Loss: Progressive sensorineural or conductive hearing loss, especially in adulthood.

- Cardiopulmonary Issues: Valve abnormalities or respiratory complications in severe types.

Diagnostic Criteria and Investigations

Clinical Assessment

Diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical signs, family history, and radiological findings. Early identification is crucial for management and prevention of complications.

Imaging Studies

- X-rays: Reveal fractures at various healing stages, bone deformities, and reduced bone density.

- DEXA Scan: Evaluates bone mineral density (BMD), particularly useful in monitoring treatment.

Genetic Testing

- Confirms mutations in collagen genes.

- Aids in precise classification and genetic counseling.

Histological Analysis

- Bone biopsy (rarely required) may show disorganized collagen fibers and reduced bone mass.

Differential Diagnosis

Conditions mimicking OI must be ruled out:

- Non-accidental injury (in children)

- Rickets

- Hypophosphatasia

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Juvenile osteoporosis

Treatment and Management Strategies

There is no definitive cure for OI, but comprehensive multidisciplinary care can significantly improve function and quality of life.

Pharmacologic Therapies

- Bisphosphonates (e.g., Pamidronate, Zoledronic Acid):

- Inhibit osteoclast activity, increase bone density, reduce fracture rate.

- Growth Hormone Therapy: Used in select cases to improve height outcomes.

- Analgesics: For pain management post-fracture or post-surgical recovery.

Orthopedic Interventions

- Intramedullary Rodding: Strengthens long bones, corrects deformities, reduces fracture frequency.

- Fracture Management: Prompt stabilization and rehabilitation are essential.

Physical and Occupational Therapy

- Muscle strengthening

- Mobility training

- Assistive device adaptation

Audiological and Dental Care

- Regular hearing assessments

- Dental rehabilitation for dentinogenesis imperfecta

Genetic Counseling and Family Support

Essential for affected families to understand inheritance patterns, recurrence risk, and prenatal testing options.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

Prognosis varies by OI type:

- Type I: Near-normal life expectancy with minor limitations.

- Type II: Typically fatal shortly after birth.

- Types III–IV: Chronic physical disabilities, requiring lifelong support, but improved prognosis with modern treatment.

Key determinants include fracture frequency, respiratory function, and spinal complications.

Research and Future Directions

Emerging therapies and experimental approaches are being explored to address the underlying collagen defect.

- Gene Therapy: Targeting mutations with CRISPR or other editing tools.

- Stem Cell Transplantation: Promising in animal models.

- Sclerostin Inhibitors: Enhancing bone formation by blocking Wnt pathway antagonists.

- Enzyme Replacement and Small Molecule Therapies: Under clinical trial evaluation.

Frequently Asked Questions:

What is the main cause of osteogenesis imperfecta?

Mutations in COL1A1 or COL1A2 genes that disrupt collagen type I synthesis.

Can osteogenesis imperfecta be cured?

There is no cure, but treatments can significantly reduce fractures and improve quality of life.

Is OI always inherited?

Most cases are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, but de novo mutations also occur.

How is OI diagnosed?

Through clinical evaluation, imaging, and confirmatory genetic testing.

What are the treatment options for OI?

Treatment includes bisphosphonates, orthopedic surgery, physical therapy, and supportive care.

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a genetically inherited disorder marked by significant bone fragility and systemic involvement. While it poses considerable challenges, advances in pharmacologic therapy, surgical techniques, and genetic research offer hope for improved outcomes. Multidisciplinary management remains essential in mitigating complications, enhancing mobility, and supporting affected individuals across the lifespan.