Opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) is a life-threatening condition characterized by a reduced drive to breathe due to the pharmacologic effects of opioid medications on the central nervous system. As opioid use continues across clinical and non-clinical settings, the risk and prevalence of OIRD remain a significant public health concern.

The Pharmacodynamics of Opioids in Respiratory Control

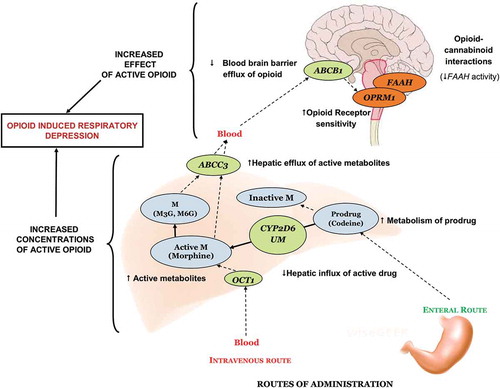

Opioids primarily exert their effects by binding to μ-opioid receptors (MORs) located throughout the central nervous system. These receptors are especially concentrated in the brainstem, where the respiratory centers—the medulla oblongata and pons—regulate breathing rhythm and response to carbon dioxide levels.

Upon activation, MORs inhibit the activity of neurons in the pre-Bötzinger complex and other critical sites involved in rhythm generation. This action blunts the brain’s sensitivity to carbon dioxide, decreases the respiratory rate, reduces tidal volume, and ultimately may cause hypoventilation or apnea.

Risk Factors for Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression

Several intrinsic and extrinsic factors increase the likelihood of developing OIRD:

- High Opioid Dosage: Elevated opioid doses, especially in opioid-naïve patients, significantly heighten risk.

- Concomitant CNS Depressants: Benzodiazepines, alcohol, and sedative-hypnotics compound respiratory suppression.

- Sleep Disorders: Conditions like obstructive sleep apnea exacerbate opioid-induced suppression of upper airway tone.

- Age and Comorbidities: Elderly individuals and patients with renal, hepatic, or pulmonary diseases face higher susceptibility.

- Genetic Polymorphisms: Variants in the OPRM1 gene and cytochrome P450 enzymes affect opioid metabolism and receptor sensitivity.

- Postoperative Patients: Use of opioids for post-surgical pain management, particularly with PCA (patient-controlled analgesia), presents increased risk due to cumulative dosing and limited monitoring.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Recognizing the clinical manifestations of OIRD is critical for timely intervention. Symptoms may include:

- Bradypnea (respiratory rate < 12/min)

- Shallow breathing or apnea

- Cyanosis or hypoxemia

- Decreased level of consciousness

- Miosis (constricted pupils)

- Snoring or gurgling sounds due to airway obstruction

Diagnosis and Monitoring

Effective diagnosis of OIRD involves both clinical observation and objective measurements:

- Pulse Oximetry: Continuous SpO₂ monitoring can detect hypoxia, though it may not identify hypoventilation until late.

- Capnography: End-tidal CO₂ monitoring is a more sensitive tool to detect early hypoventilation.

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG): Reveals hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis, confirming impaired gas exchange.

Routine assessment of sedation level using scales such as the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) or Pasero Opioid-Induced Sedation Scale (POSS) can help identify patients at risk.

Management and Treatment

Immediate Interventions

- Airway Support: Ensure airway patency using repositioning or adjuncts (e.g., oropharyngeal airway).

- Oxygen Supplementation: Administer supplemental oxygen to maintain adequate saturation.

- Naloxone Administration: Naloxone, a competitive opioid receptor antagonist, reverses respiratory depression rapidly. It can be administered via IV, IM, SC, or intranasally.

- Initial dose: 0.04–0.4 mg IV

- Titrate cautiously to avoid complete reversal, which may induce withdrawal

Ongoing Care

- Wean or discontinue opioids as clinically indicated.

- Use multimodal analgesia to reduce reliance on opioids—consider NSAIDs, acetaminophen, nerve blocks, or non-opioid adjuvants.

- Continuous respiratory monitoring in high-risk settings such as ICUs or post-op recovery units.

Preventive Strategies in Clinical Practice

To minimize the incidence of OIRD, proactive measures should be integrated into patient care protocols:

- Risk Stratification: Evaluate patients’ history, comorbidities, and concurrent medications before opioid administration.

- Education and Training: Ensure clinicians are trained in opioid titration, monitoring, and naloxone usage.

- Technology Integration: Employ smart PCA pumps with built-in respiratory monitoring to prevent overdose.

- Prescribing Guidelines: Adhere to institutional and CDC-recommended opioid prescribing frameworks.

Special Considerations for Chronic Opioid Users

Patients on long-term opioid therapy may develop tolerance to analgesia without corresponding tolerance to respiratory depression. Strategies include:

- Routine reevaluation of pain management plans

- Tapering protocols to reduce dependency

- Inclusion of addiction specialists and behavioral support

Naloxone in Community and Outpatient Settings

The expansion of naloxone access—via take-home kits and over-the-counter availability—has become a vital public health initiative. Education on its usage among caregivers, first responders, and patients enhances preparedness for accidental overdose scenarios.

Emerging Therapies and Research Directions

Investigational therapies aim to dissociate analgesic effects from respiratory depression. These include:

- Biased Agonists: Novel agents like oliceridine (TRV130) selectively activate G-protein pathways without β-arrestin recruitment.

- Non-Opioid Analgesics: Research continues on cannabinoid-based and sodium-channel-blocking agents.

- Genetic Screening Tools: To personalize opioid prescriptions and mitigate risk.

FAQs

What is the primary cause of opioid-induced respiratory depression?

Opioids depress the brainstem respiratory centers by binding to μ-opioid receptors, reducing the response to CO₂ and decreasing respiratory drive.

How can respiratory depression be detected early?

Capnography is the most sensitive method for early detection by monitoring CO₂ levels; pulse oximetry and sedation scales also aid in monitoring.

Is naloxone safe to use outside hospital settings?

Yes, naloxone is widely used in community settings and is safe when administered appropriately in suspected opioid overdose situations.

Can opioid-induced respiratory depression be fatal?

Yes, without prompt intervention, OIRD can lead to respiratory arrest and death.

Who is most at risk for OIRD?

Opioid-naïve individuals, elderly patients, those with sleep apnea or organ dysfunction, and those using multiple CNS depressants are at increased risk.