Opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD) remains one of the most critical and potentially fatal complications associated with opioid therapy. As opioid analgesics continue to be essential in the management of moderate to severe pain, especially in perioperative, palliative, and chronic pain settings, implementing robust prophylactic measures is vital to reduce the risk of respiratory compromise. Our focus herein is to provide clinicians with a comprehensive understanding of OIRD prophylaxis, encompassing risk stratification, monitoring, and pharmacologic interventions.

Understanding Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression

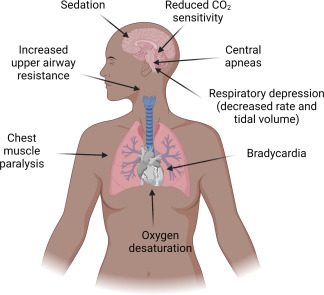

OIRD refers to a reduction in the ventilatory response to hypercapnia and hypoxia due to the μ-opioid receptor agonist effects of opioids on the brainstem respiratory centers. This leads to hypoventilation, increased carbon dioxide retention, and if untreated, hypoxia, cardiac arrest, or death.

Risk Factors for Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression

Patient-Related Risk Factors

- Age >65 years

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

- Obesity (BMI >30)

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Renal or hepatic impairment

- Neurological disorders

- Concurrent use of CNS depressants (e.g., benzodiazepines, alcohol)

Therapy-Related Risk Factors

- High opioid doses or rapid dose titration

- Use of long-acting opioids

- Combination with sedatives or muscle relaxants

- Opioid-naïve status

- Postoperative opioid administration without appropriate monitoring

Mechanism of Opioid Respiratory Depression

The suppression of the pre-Bötzinger complex, responsible for rhythm generation, results in a blunted ventilatory response to increased PaCO₂ and decreased PaO₂.

Clinical Assessment and Monitoring Strategies

Initial Risk Stratification

Before initiating opioids, thorough risk assessment must be conducted. Screening tools such as the STOP-Bang Questionnaire and ORP (Opioid Risk Prediction) can be instrumental.

Continuous Monitoring Parameters

- Pulse oximetry: Detects hypoxemia but may not catch early hypoventilation.

- Capnography (ETCO₂ monitoring): Gold standard for detecting hypoventilation and CO₂ retention.

- Respiratory rate and level of consciousness: Essential bedside parameters.

Continuous respiratory monitoring is especially warranted in postoperative settings and for high-risk patients.

Pharmacological Approaches to Prophylaxis

1. Opioid Dose Optimization

- Start with the lowest effective dose

- Avoid rapid titration, especially in opioid-naïve individuals

- Utilize multimodal analgesia to reduce opioid needs

2. Use of Opioid Antagonists

Naloxone

- Low-dose naloxone infusions (e.g., 0.25–1 mcg/kg/hr) can mitigate respiratory depression without reversing analgesia.

- Intranasal or IM naloxone should be readily available for emergency use in all opioid-administered environments.

Naldemedine and Methylnaltrexone

- Peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs) used primarily for opioid-induced constipation but may have ancillary roles in reducing systemic effects.

3. Respiratory Stimulants

Agents such as doxapram and ampakines are under investigation for their role in countering OIRD by stimulating respiratory centers without affecting analgesia.

Multimodal and Non-Pharmacologic Approaches

Regional and Non-Opioid Analgesia

- Neuraxial blocks (epidural/spinal)

- Peripheral nerve blocks

- Non-opioid medications: NSAIDs, acetaminophen, gabapentinoids, ketamine

Sedation Protocols

Avoid co-prescription of benzodiazepines, especially in patients with OSA or elderly populations. Adopt sedation scoring systems (e.g., RASS, Pasero Opioid-Induced Sedation Scale) to balance pain control and safety.

Special Considerations in High-Risk Populations

Postoperative and Hospital Settings

- Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols recommend opioid-sparing strategies

- Continuous capnography and nurse-administered sedation scoring

- Routine use of PCA (Patient-Controlled Analgesia) with integrated safety limits

Palliative Care and Chronic Pain

- Regular reevaluation of opioid effectiveness and necessity

- Use of extended-release formulations with caution

- Close caregiver education on recognizing signs of respiratory depression

Emerging Therapies and Future Perspectives

Biased μ-Opioid Agonists

New agents such as oliceridine (TRV130) show promise by selectively activating G-protein pathways while minimizing β-arrestin signaling, reducing OIRD risk.

Artificial Intelligence and Smart Monitoring

Real-time monitoring systems using AI can detect early warning signs and predict OIRD with greater precision than traditional protocols.

Frequently Asked Questions:

Q1: What is the earliest sign of opioid-induced respiratory depression?

Reduced respiratory rate and decreased level of consciousness are early signs; capnography may detect hypoventilation before hypoxia sets in.

Q2: Is naloxone always required when prescribing opioids?

In high-risk populations, prescribing naloxone for emergency use is recommended and often mandated by guidelines.

Q3: Can opioid-induced respiratory depression occur with therapeutic doses?

Yes. Even standard doses can cause respiratory compromise, especially in susceptible individuals.

Q4: How does capnography differ from pulse oximetry in detecting OIRD?

Capnography measures ventilation and can detect changes before oxygen saturation drops, making it more sensitive for early detection.

Q5: Can patients with sleep apnea safely take opioids?

Caution is advised. They are at increased risk and should be closely monitored, preferably with non-opioid or regional alternatives.

Preventing opioid-induced respiratory depression requires a comprehensive, multifactorial approach that includes vigilant risk assessment, strategic dose management, and proactive monitoring protocols. By integrating pharmacologic prophylaxis, technology-enhanced monitoring, and opioid-sparing strategies, healthcare providers can significantly mitigate the risks associated with opioid therapy, ensuring both patient safety and effective pain relief.