Ocular Histoplasmosis Syndrome (OHS), also known as Presumed Ocular Histoplasmosis Syndrome (POHS), is a serious eye condition that can lead to progressive vision loss. It is believed to result from exposure to the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum, primarily affecting individuals who live in areas where the organism is endemic, such as the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys.

Although the initial histoplasma infection typically causes mild or no symptoms, ocular manifestations may appear years later, causing damage to the retina and choroid, often without any signs of active inflammation.

Causes and Pathophysiology of Ocular Histoplasmosis

The fungus Histoplasma capsulatum is inhaled into the lungs, where it may cause a pulmonary infection. In susceptible individuals, the organism can disseminate hematogenously, lodging in the choroidal vasculature of the eye. Although inactive, this can lead to scarring and neovascularization later in life.

Risk Factors and Geographic Distribution

- Geographic location: Predominantly affects individuals in the Midwestern and Southeastern United States

- Exposure to bird or bat droppings: Especially in caves, chicken coops, and old buildings

- Immune response: Genetic or immunological predispositions may influence ocular involvement

- Age: More common in adults aged 20–50

Recognizing Symptoms of Ocular Histoplasmosis

Early Signs

- Small, punched-out scars (called histo spots) in the retina

- Typically asymptomatic in early stages

- Detected incidentally during routine eye exams

Vision-Threatening Features

- Blurred or distorted vision (metamorphopsia)

- Central scotomas (dark spots in the center of vision)

- Decreased visual acuity

- Sudden worsening of central vision suggests choroidal neovascularization (CNV)

Key Diagnostic Criteria for Ocular Histoplasmosis

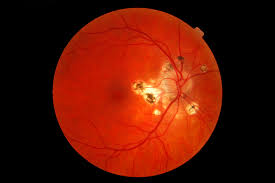

Diagnosis is primarily clinical and based on characteristic fundoscopic findings in the absence of inflammation.

Classic Triad of POHS:

- Peripapillary atrophy (scarring around the optic disc)

- Punched-out chorioretinal scars (histo spots) in the macular or peripheral retina

- Macular choroidal neovascularization causing fluid and hemorrhage

Diagnostic Tools

- Fundus Photography: Reveals characteristic lesions

- Fluorescein Angiography (FA): Highlights areas of neovascular leakage

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): Detects subretinal fluid and CNV

- OCT-Angiography (OCT-A): Non-invasive method for identifying abnormal blood vessels

- Visual Acuity Testing: Tracks disease progression and response to treatment

Complications: Choroidal Neovascularization

The most severe complication of POHS is choroidal neovascularization, where abnormal blood vessels grow beneath the retina and leak fluid or blood.

Consequences of CNV:

- Irreversible central vision loss if untreated

- Retinal scarring after hemorrhages

- Possible legal blindness in advanced stages

Differential Diagnosis

It is essential to distinguish POHS from other retinal diseases:

- Toxoplasmosis retinochoroiditis: Active inflammation with vitritis

- Sarcoidosis: Granulomatous uveitis with systemic signs

- Multifocal choroiditis: Bilateral inflammation and scarring

- Age-related macular degeneration (AMD): CNV in older adults, drusen presence

Treatment Options for Ocular Histoplasmosis

1. Anti-VEGF Intravitreal Injections

First-line therapy for CNV secondary to POHS.

- Agents: Ranibizumab, Aflibercept, Bevacizumab

- Mechanism: Inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), reducing abnormal vessel growth

- Frequency: Administered monthly during active phases, then extended

2. Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

Utilizes verteporfin (a light-sensitive drug) and laser activation to target neovascular tissue.

- Used when anti-VEGF response is suboptimal

- Less common due to advancements in anti-VEGF therapy

3. Laser Photocoagulation

- Targets extrafoveal CNV

- Rarely used due to risk of collateral retinal damage and superior alternatives

4. Observation

For inactive lesions or asymptomatic histo spots, no immediate treatment is necessary. Close monitoring is essential.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

- Early detection and treatment of CNV lead to significantly better visual outcomes

- Most patients maintain functional vision with timely anti-VEGF therapy

- Bilateral involvement occurs in ~50% of cases over time

- Lifelong monitoring is recommended for high-risk individuals

Preventive Measures and Patient Education

- Avoid exposure to environments with high concentrations of bird or bat droppings

- Individuals in endemic areas should report visual disturbances immediately

- Routine annual eye exams are critical for those with known histo spots

- Use of Amsler Grid at home can help detect early CNV symptoms

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Can ocular histoplasmosis cause total blindness?

It rarely causes total blindness but can lead to severe central vision loss if left untreated.

Q2: Is ocular histoplasmosis contagious?

No, the disease is not transmitted person to person.

Q3: Can children develop POHS?

It is extremely rare in children; typically affects adults between 20–50 years.

Q4: How often should I get my eyes checked if I have histo spots?

Annual examinations are recommended, with immediate evaluation if vision changes occur.

Q5: Will I need injections forever?

Some patients may need long-term intermittent therapy, but others respond well to initial treatments and require fewer injections over time.

Ocular Histoplasmosis is a significant cause of vision impairment, especially in individuals from endemic regions. Although often silent in its early stages, its potential to cause irreversible central vision loss through choroidal neovascularization makes early detection and intervention critical. Through comprehensive diagnostic imaging, effective anti-VEGF therapy, and ongoing surveillance, we can greatly improve patient outcomes and preserve sight. Regular patient education and awareness remain pivotal in reducing the long-term impact of this sight-threatening condition.