Nosocomial bacterial pneumonia—commonly referred to as hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)—is a severe respiratory infection that develops 48 hours or more after hospital admission. A subset of HAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), occurs in patients who have been mechanically ventilated for at least 48 hours. Both conditions are associated with high morbidity, prolonged hospital stays, increased healthcare costs, and elevated mortality rates.

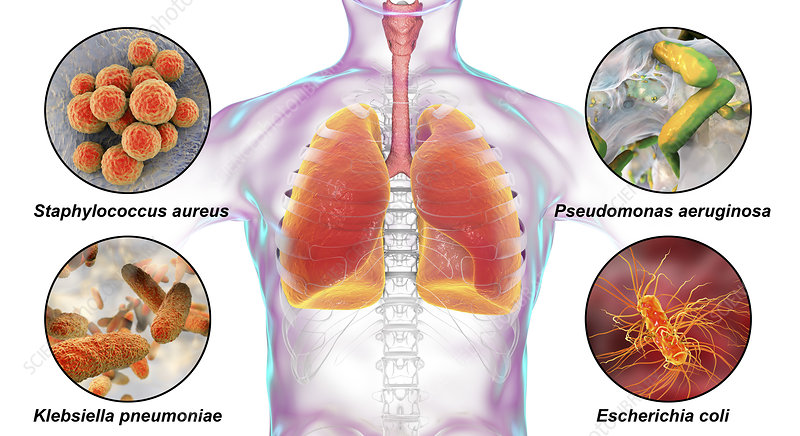

Etiological Agents: Key Bacterial Pathogens

The primary pathogens responsible for nosocomial bacterial pneumonia are often gram-negative bacteria, though gram-positive organisms also contribute significantly. These pathogens frequently exhibit multidrug resistance (MDR), complicating treatment.

Common Causative Bacteria

| Pathogen | Type | Resistance Potential |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Gram-negative | MDR, XDR |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Gram-negative | ESBL and carbapenem-resistant |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Gram-negative | MDR, pan-resistant strains |

| Escherichia coli | Gram-negative | ESBL-producing |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | Gram-positive | Methicillin-resistant |

| Enterobacter spp. | Gram-negative | AmpC beta-lactamase producers |

These organisms thrive in hospital environments and can colonize respiratory equipment, hands of healthcare workers, and surfaces near the patient.

Pathogenesis: Mechanisms of Infection in Hospital Settings

Hospitalized patients are exposed to numerous risk factors that compromise their immune defenses and increase susceptibility to infection.

Risk Factors for Nosocomial Pneumonia

Key contributors include:

- Endotracheal intubation

- Immunosuppressive therapy

- Prolonged ICU stay

- Aspiration of gastric contents

- Broad-spectrum antibiotic exposure

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Criteria

Nosocomial bacterial pneumonia typically presents with nonspecific symptoms that overlap with other hospital-acquired infections. Prompt diagnosis is critical to prevent deterioration.

Common Signs and Symptoms

- Fever or hypothermia

- New or progressive pulmonary infiltrates on chest imaging

- Leukocytosis or leukopenia

- Purulent tracheal secretions

- Oxygen desaturation or increased ventilatory requirements

Diagnostic Methods

1. Radiological Imaging

- Chest X-ray: Infiltrates, consolidation

- CT scan: Useful in complex cases or unclear findings

2. Microbiological Testing

- Endotracheal aspirate culture (ETA)

- Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)

- Protected specimen brush (PSB)

- Blood cultures

3. Biomarkers

- Procalcitonin (PCT): Helps differentiate bacterial from non-bacterial causes

- C-reactive protein (CRP): Nonspecific marker of inflammation

Classification: HAP vs. VAP

| Parameter | HAP | VAP |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | ≥48 hrs after admission | ≥48 hrs after endotracheal intubation |

| Ventilation requirement | Not necessary | Required |

| Common pathogens | Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, MRSA | Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, MRSA |

| Diagnostic tools | Clinical and radiologic + sputum culture | BAL, PSB, ETA + imaging |

| Associated mortality | 15–30% | 30–50% |

Antimicrobial Therapy: Empiric and Targeted Approaches

Timely administration of effective antibiotics is essential to reduce complications. Therapy must balance the need for adequate coverage against the risks of promoting resistance.

Empiric Therapy (Pending Culture Results)

For HAP/VAP without MDR risk factors:

- Piperacillin-tazobactam

- Cefepime

- Levofloxacin

- Meropenem (in severe illness or septic shock)

For HAP/VAP with MDR risk factors or known colonization:

- Antipseudomonal beta-lactam (e.g., ceftazidime, meropenem)

- MRSA coverage (vancomycin or linezolid)

- Dual antipseudomonal therapy may be considered (e.g., beta-lactam + aminoglycoside)

De-escalation Strategy

After pathogen identification and susceptibility testing:

- Narrow-spectrum antibiotics

- Shorten treatment duration (usually 7 days)

- Avoid unnecessary dual therapy

Prevention Strategies in Clinical Practice

Proactive measures can significantly lower the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia.

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP) Prevention Bundle

- Elevate head of bed 30–45 degrees

- Daily sedation vacations and assessment for extubation

- Oral hygiene with chlorhexidine

- Avoid gastric overdistension

- Subglottic secretion drainage

Additional Measures

- Hand hygiene compliance

- Proper disinfection of respiratory equipment

- Judicious use of antibiotics

- Staff education and surveillance programs

Complications and Long-Term Outcomes

Untreated or poorly managed nosocomial pneumonia can lead to serious complications such as:

- Septic shock

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Empyema

- Multiorgan failure

- Prolonged mechanical ventilation

- Increased risk of death, especially in elderly and immunocompromised patients

Emerging Therapies and Future Perspectives

Ongoing research aims to combat antimicrobial resistance and improve outcomes through innovative therapies.

Notable Advances

- Nebulized antibiotics for localized delivery (e.g., amikacin liposome inhalation)

- Monoclonal antibodies targeting virulence factors

- Phage therapy for MDR organisms

- Rapid molecular diagnostics for faster pathogen detection (PCR-based, NGS)

- Artificial intelligence in early diagnosis and antimicrobial stewardship

Frequently Asked Questions:

What is nosocomial bacterial pneumonia?

A hospital-acquired lung infection caused by bacteria, occurring 48 hours or more after admission.

How does it differ from community-acquired pneumonia?

It involves different pathogens, often multidrug-resistant, and develops in hospitalized patients.

Which bacteria are commonly involved?

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and MRSA are frequently implicated.

How is nosocomial pneumonia diagnosed?

Diagnosis is based on clinical signs, radiological imaging, and microbiological cultures from respiratory specimens.

Can nosocomial pneumonia be prevented?

Yes, through infection control measures, ventilator care bundles, and judicious antibiotic use.

Nosocomial bacterial pneumonia remains a formidable challenge in healthcare settings. Its management requires a multidisciplinary approach involving rapid diagnosis, appropriate empiric and targeted therapy, and vigilant infection prevention strategies. As antimicrobial resistance continues to rise, tailored treatments, technological innovations, and prevention protocols are essential to improve patient outcomes and safeguard the efficacy of existing therapeutics.