Macular edema is a leading cause of vision impairment in patients with non-infectious uveitis. It occurs when fluid accumulates in the macula, leading to swelling and blurred vision. Uveitis, an inflammatory condition affecting the uveal tract, can be of infectious or non-infectious origin. In cases of non-infectious uveitis, immune system dysregulation plays a key role in triggering inflammation and subsequent macular edema.

Understanding Non-Infectious Uveitis

Non-infectious uveitis is an intraocular inflammatory disorder that is not caused by bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic infections. Instead, it is often linked to autoimmune diseases such as:

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Sarcoidosis

- Behçet’s disease

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease

The condition may be classified based on the anatomical location of inflammation:

- Anterior uveitis (most common, affecting the front of the eye)

- Intermediate uveitis (involves the vitreous and ciliary body)

- Posterior uveitis (affects the retina and choroid)

- Panuveitis (involves all parts of the uveal tract)

Pathophysiology of Macular Edema in Non-Infectious Uveitis

Macular edema results from the breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier due to persistent inflammation. This leads to increased vascular permeability, allowing fluid to leak into the macula. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), contribute to this process.

Symptoms of Macular Edema in Non-Infectious Uveitis

Patients with macular edema due to uveitis may experience:

- Blurred or distorted vision

- Reduced central vision

- Increased sensitivity to light

- Difficulty reading or recognizing faces

- Colors appearing washed out

Diagnostic Approaches

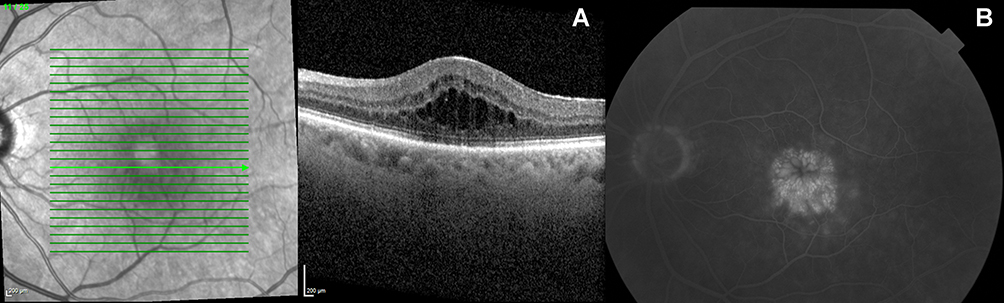

Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for preventing vision loss. Key diagnostic tools include:

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): Provides high-resolution imaging of macular thickness and fluid accumulation.

- Fluorescein Angiography (FA): Detects vascular leakage in the retina.

- Indocyanine Green Angiography (ICGA): Helps identify choroidal involvement.

- Fundus Examination: Evaluates the extent of retinal inflammation.

Treatment Options for Macular Edema Associated with Non-Infectious Uveitis

Treatment strategies aim to control inflammation and reduce macular swelling.

1. Corticosteroid Therapy

- Topical corticosteroids (e.g., prednisolone acetate) for anterior uveitis.

- Periocular or intravitreal corticosteroids (e.g., triamcinolone acetonide, dexamethasone implant) for localized treatment.

- Systemic corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) for severe cases.

2. Immunomodulatory Therapy (IMT)

- Non-biologic agents: Methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil.

- Biologic agents: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors like adalimumab or interleukin inhibitors (e.g., tocilizumab) for refractory cases.

3. Anti-VEGF Therapy

- Intravitreal injections of ranibizumab or aflibercept help reduce vascular permeability and fluid accumulation.

4. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

- Oral or topical NSAIDs like ketorolac may provide additional benefits in reducing inflammation.

5. Surgical Interventions

- Vitrectomy: Considered for chronic, non-resolving cases where inflammatory debris affects vision.

Prognosis and Long-Term Management

The prognosis depends on early diagnosis and effective treatment. Long-term monitoring with OCT and regular ophthalmologic assessments is essential to prevent recurrences and complications like retinal scarring or permanent vision loss.

Macular edema in non-infectious uveitis is a serious condition that requires prompt intervention to prevent visual deterioration. With advancements in imaging and targeted therapies, personalized treatment approaches can significantly improve outcomes. Patients should seek regular follow-ups to manage inflammation effectively and maintain optimal visual health.