Escherichia coli (E. coli), a Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic bacillus, is widely known for causing urinary tract infections, sepsis, and intra-abdominal infections. However, its role as a pathogen in pneumonia is often overlooked. E. coli pneumonia, though less common than other bacterial pneumonias, is a significant concern, particularly in hospital-acquired settings. This article delves into the epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of E. coli pneumonia.

Epidemiology of Escherichia coli Pneumonia

E. coli pneumonia primarily occurs in hospitalized patients, particularly those with prolonged mechanical ventilation or underlying health conditions. It is more common in:

- Nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections – Patients in intensive care units (ICUs) with ventilators or catheters are at increased risk.

- Immunocompromised individuals – Patients with diabetes, cancer, or undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.

- Aspiration-prone patients – Those with neurological disorders or altered consciousness who are more likely to aspirate gastric contents.

- Antibiotic exposure – Prolonged or inappropriate antibiotic use may lead to multidrug-resistant (MDR) E. coli infections.

While E. coli pneumonia is predominantly nosocomial, community-acquired cases have been reported, particularly in individuals with chronic illnesses or previous antibiotic exposure.

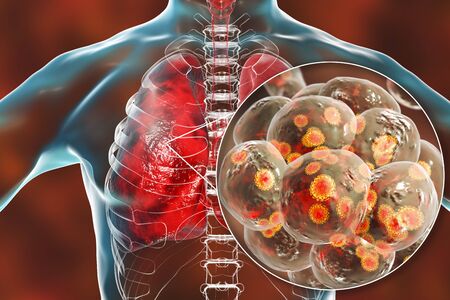

Pathogenesis of Escherichia coli Pneumonia

The development of E. coli pneumonia involves several key mechanisms:

- Colonization of the Respiratory Tract

- E. coli may colonize the oropharynx, especially in critically ill patients.

- Antibiotic use can disrupt normal flora, allowing E. coli overgrowth.

- Aspiration and Lower Respiratory Tract Invasion

- Microaspiration of colonized secretions introduces E. coli into the lungs.

- Direct hematogenous spread from a primary infection (e.g., urinary tract or bloodstream infection) can also lead to pulmonary involvement.

- Immune Evasion and Virulence Factors

- E. coli produces adhesins, lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and toxins that facilitate immune evasion.

- Certain strains, such as extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli, exhibit enhanced resistance to host defenses.

- Inflammatory Response and Lung Damage

- Neutrophilic infiltration leads to alveolar damage, exudate formation, and consolidation, characteristic of pneumonia.

- Severe cases may progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or septic shock.

Clinical Manifestations of Escherichia coli Pneumonia

Patients with E. coli pneumonia present with a spectrum of symptoms ranging from mild to severe, including:

- Fever and chills – Often indicative of systemic infection.

- Productive cough – Purulent, sometimes blood-tinged sputum.

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath) – Due to alveolar consolidation.

- Pleuritic chest pain – Especially if pleural involvement occurs.

- Tachypnea and hypoxia – More prominent in severe cases.

- Sepsis and septic shock – Common in MDR strains and immunocompromised patients.

Nosocomial cases are often more severe due to the presence of drug-resistant strains.

Diagnosis of Escherichia coli Pneumonia

Accurate diagnosis is essential to ensure appropriate treatment. Diagnostic approaches include:

1. Clinical Assessment

- History of hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, or antibiotic use.

- Symptoms consistent with pneumonia.

2. Imaging Studies

- Chest X-ray: Lobar or multifocal infiltrates.

- CT Scan: More detailed assessment of lung involvement.

3. Microbiological Testing

- Sputum Culture: Identifies E. coli and its antibiotic susceptibility.

- Blood Culture: Detects bacteremia, common in severe infections.

- Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL): Used in ventilated patients for pathogen identification.

4. Laboratory Markers

- Leukocytosis with neutrophilia in bacterial infections.

- Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin indicating severe infection.

Treatment of Escherichia coli Pneumonia

1. Empirical Antibiotic Therapy

- Initial broad-spectrum coverage is necessary due to potential drug resistance.

- Carbapenems (e.g., meropenem, imipenem) – Preferred for ESBL-producing E. coli.

- Piperacillin-tazobactam – Used for non-resistant strains.

- Cefepime or ceftazidime – Alternative agents in moderate cases.

- Aminoglycosides or fluoroquinolones – Used in combination therapy.

2. Targeted Therapy

- Once susceptibility results are available, de-escalation to a narrower-spectrum antibiotic is recommended to prevent resistance.

3. Supportive Care

- Oxygen therapy for hypoxia.

- Mechanical ventilation in severe respiratory distress.

- Fluid resuscitation and vasopressors if septic shock develops.

Prevention of Escherichia coli Pneumonia

Preventing E. coli pneumonia is particularly crucial in healthcare settings. Strategies include:

1. Infection Control Measures

- Hand hygiene compliance among healthcare workers.

- Strict isolation for MDR E. coli cases.

- Proper sterilization of medical equipment.

2. Antimicrobial Stewardship

- Judicious use of antibiotics to prevent resistance.

- Regular surveillance for MDR pathogens.

3. Prevention of Aspiration

- Elevating the head of the bed in ventilated patients.

- Early mobilization of hospitalized patients.

4. Vaccine Development

- While no vaccine currently exists for E. coli pneumonia, research is ongoing to develop targeted immunoprophylaxis.