Citrobacter meningitis is a rare but severe bacterial infection that affects the central nervous system (CNS). It is predominantly seen in neonates and immunocompromised individuals, making timely diagnosis and treatment critical to prevent long-term complications. This article provides an in-depth exploration of the causes, clinical presentation, diagnostic approaches, treatment options, and preventive measures associated with Citrobacter meningitis.

Causes and Pathogenesis

Overview of Citrobacter Species

Citrobacter is a genus of Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic bacilli belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family. Among the species, Citrobacter koseri (formerly Citrobacter diversus) is the most commonly implicated pathogen in meningitis cases, particularly in neonates.

Pathogenesis

The infection typically arises from hematogenous spread following bacteremia. In neonates, maternal-fetal transmission during childbirth or nosocomial infections in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) are significant risk factors. The bacterium’s ability to invade the CNS and form abscesses is linked to its production of exotoxins and lipopolysaccharides, which disrupt the blood-brain barrier and cause inflammation.

Risk Factors

- Neonates: Prematurity, low birth weight, and prolonged hospital stays increase susceptibility.

- Immunocompromised Individuals: Conditions such as cancer, HIV/AIDS, or immunosuppressive therapy heighten the risk.

- Healthcare-Associated Infections: Use of medical devices like catheters or ventilators in hospital settings can facilitate infection.

Clinical Presentation

Neonatal Symptoms

- Lethargy

- Poor feeding

- High-pitched crying

- Bulging fontanelle

- Seizures

Symptoms in Older Children and Adults

- Fever

- Headache

- Stiff neck

- Nausea and vomiting

- Altered mental status

The progression can be rapid, leading to severe complications such as cerebral abscesses, hydrocephalus, and seizures if untreated.

Diagnosis

Laboratory Tests

- Blood Cultures: Identification of Citrobacter species in blood samples.

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis: Elevated white blood cell count, high protein levels, and low glucose concentrations are indicative of bacterial meningitis.

Imaging Studies

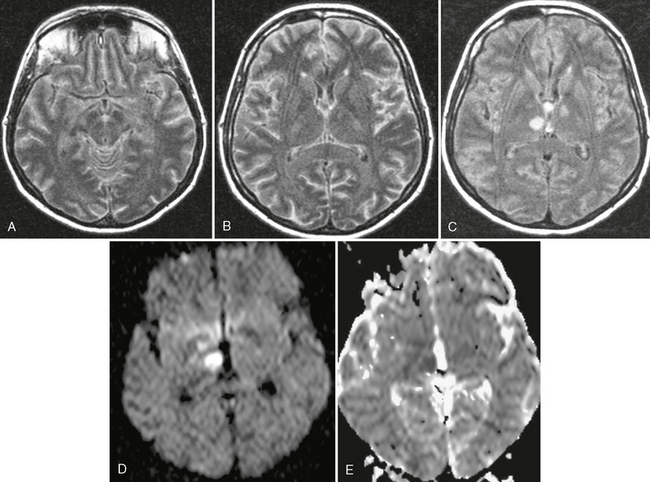

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Useful for detecting complications such as abscesses or hydrocephalus.

- Computed Tomography (CT): Performed in cases where there is a risk of raised intracranial pressure.

Molecular Diagnostics

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Provides rapid and specific identification of Citrobacter DNA in clinical samples.

Treatment

Antimicrobial Therapy

Empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated promptly, followed by targeted therapy based on culture and sensitivity results. Commonly used antibiotics include:

- Third-Generation Cephalosporins: Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime

- Carbapenems: Meropenem

The duration of treatment typically ranges from 3 to 6 weeks, depending on the severity and presence of complications.

Supportive Care

- Management of seizures with anticonvulsants

- Monitoring and control of intracranial pressure

- Nutritional and fluid support

Surgical Interventions

In cases of abscess formation or hydrocephalus, surgical drainage or placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt may be required.

Prognosis

The prognosis of Citrobacter meningitis varies depending on the timeliness of diagnosis and treatment. Neonates are at a higher risk of long-term neurological sequelae, including developmental delays, cerebral palsy, and hearing loss. Mortality rates remain significant, underscoring the need for prompt medical intervention.

Prevention

Maternal Health

- Routine prenatal care to identify and manage infections during pregnancy.

Infection Control in Healthcare Settings

- Strict adherence to hygiene protocols in NICUs.

- Appropriate use and management of medical devices.

Vaccination

While no specific vaccine exists for Citrobacter species, general immunizations against common bacterial pathogens can reduce secondary infections.